Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

An American girl

|

|

Nahid gave a party once, and there was beer and music and dancing. One of the guests got drunk and started shaking his finger in my face, yelling, “You Americans, you don’t care about us; you are a bullshit people! ” and everyone else was shocked and shushed him because he was not being hospitable to me, and Nahid smiled apologetically and sipped her beer, and the musicians played one more song, one more song on their Afghan instruments, until it was three in the morning, and they gave me a bed to sleep in and the next morning they gave me breakfast. But I could not forget that I had seen Nahid drinking beer. She was becoming an American. — “I don’t know if the fighting is going to stop or how long it’s going to take, ” she said to me passionately, defensively, “and when you’re young you have to do something, to be something where you are. My grandmother and my mother, they are older and will never be reconciled to living here. They want to go back because it’s very hard for them: they don’t speak the language, and they’re mostly alone because everyone else goes to work or school. But I think if Russians leave my country, then everything will be okay. I think most of us would like to go back. I do.” —Her head was down; her voice was very low. — “I would like to go back to help my people, to stay there. But then again, I don’t know if …” —She stopped. — “I don’t want to go back to my country and see that everything has changed so that I can’t— bear it anymore.”

* Nomads.

† In Europe the consulates were more willing than in Pakistan to grant visas to the United States. Lucky Nahid only had to wait for half a year!

7. “… DESCRIBED FORMALLY AS REFUGEE CAMPS …”: WOMEN (1982)

Many centers described formally as refugee camps were set up in the territory of Pakistan. Armed groups that are sent into Afghanistan undergo training there. It is in these camps that they sit it out or are being rallied after making raids on populated Afghan localities and communications and other projects. Among instructors training these units are members of the U.S. Secret Services, Chinese experts in so-called “guerrilla operations” and even specialists in subversive operations from Egypt.

TASS STATEMENT, 1979

“… Described formally as refugee camps …”

The Young Man had expected the refugee centers to look like pictures of concentration camps set in pictures of the Gobi Desert: barbed wire, jaundiced children dying of thirst, work gangs, sentries and corpses in the sand. He can, I think, be forgiven this lack of insight. For an American in 1982, the most practical course was to assume the worst about conditions in Asia. (Now we can fear and hate Asians instead, since they are taking over our markets.) At that time we were sufficiently far away for only the most important news to reach us — and when was the last time that important news was good? Before the Young Man left the United States, a Pakistani doctor had given a talk to an A.F.A.R. meeting. The doctor had worked in the camps. He said that conditions in the camps run by Pakistan alone tended to be worse than in those administered by the U.N. and the voluntary agencies. Some were much worse. But all were bad. Hearing this, the Young Man had felt anguish. It was still four months before he was to leave for Pakistan, and in that time how many more refugees would die? If only he could go tomorrow! Then he could accomplish something that much sooner.* —Of course the U.N.H.C.R. nutritionist in Peshawar, Marie Sardie, was in the right when she said to him, “I hate typical Western propaganda about Eastern countries: you know, the begging bowls. I hate that. It’s this whole attitude that if someone’s actually dying, then you help them. But if they look okay, then forget it, Charlie. And this is defeating everything about development.” —And yet she was missing a point, because the refugees, being refugees, were by definition not okay. — Can we blame the do-gooder, then, whose urgency planted the camps with imaginary barbed wire?

No, he was right.

If I could speak to the Young Man now, what would I say to him? I can’t deny that I feel very dull now. There was some excitement and belief that the Young Man had that I don’t have. But although my life is flat, it is content with its flatness. I am a success. It is only that sometimes, when I read over his words, something brushes against me like a soft garment, and I feel a pang. What have I lost? If I set out to Help Somebody now, I know that I would be more effective, that I would accomplish more, give more, take less. — For a time the Young Man embarrassed me. Now, despite all his ignorance, I admire him a little. I wish that I could be more like him. But when I was him, I got hurt. — What about the saints, and Albert Schweitzer? Their existence proves that it is possible to be inspirational and effective. But did they feel inspired? Is inspiration an indulgence?

Mainly, the Young Man’s careful records bore me. He never thought to ask for stories: all he wanted was facts. Those facts are largely meaningless now. All that I have left now are the things that his fact-crusher could not quite digest: debris and colored bric-a-brac, like the old woman with tuberculosis who let him look at her as she sat out on the hard clay ground beside her house, the red shawl flaming about her gray hair, a silver ring on her finger; and her face was almost impossibly lined and wrinkled and beaten but he could not honestly tell her mood or what she was thinking or anything about her except that she was looking back at him, her mouth wrinkled in emotion — but which emotion? — or was it emotion at all? — and the men stood in a line behind, scowling at him as he watched her. — What can she mean or be for me now except another person whom I annoyed or perhaps even tortured with my good intentions? I can’t forget her but she isn’t alive. But the hand that wrote those records in the battered notebook, those tanned fingers dancing upon the keyboard of my computer now in front of my eyes, that hand fascinates me: it has traveled on a voyage to a place where I have never been.

And yet there is something despicable about it, too.

The do-gooder wanted to do good; he wanted exotic distress to remedy, so he had a sinking feeling on discovering less of that than he had anticipated. To his uneducated eye, it was not always so easy to tell the difference in condition between refugees and locals: neither had what he had! (Whereas those refugee camps in Thailand really had barbed wire; the Young Man saw it on TV.)

The stories — yes, those were sad, but although he thought he believed them, he didn’t; that took a few years of bad dreams. The Afghans could go freely in and out of their camps, and while malnutrition was widespread, starvation seemed nonexistent. The men retained their weapons and frequently slipped back across the border to take part in the jihad. To his eye the camps did not seem to be cesspools of misery at all, but rather festive and “ethnic” like one of those big Fords decorated by Pathan truckers until it was more gorgeous than any Karachi bus, the way its pennant pointed grandly down, bearing in its blackness the many-colored wheel-circle, and its paintings of mosques in blue and gold, captioned by Pushtu cursive like white snakes or breakers, ranged all around the top of the cab, framed by golden waves, and sun and dust had bleached these colors to a milky delicacy so that the truck had become a tea-tin from some dream-Persia, and clusters of bright streamers grew down across the windshield and the son and father leaned against the hood squinting at the Young Man; the tiny daughter, already wearing the long strip of flower-patterned cloth over her hair, gaped at the Young Man in pure frankness, clutching at her throat with one hand, holding a ricepot in the other, and the horizon was nothing but a dusty ridge — so too in the camps with the young girls in their bright-patterned garments, the mud houses graced by sunflowers, the extraordinary strength and handsomeness of the people, the sun and the cloudless sky. — Here for once I do not judge the Young Man so harshly. What if Saint George had come all the way across the Mountains of Doom and found no dragon to slay? Of course he’d be happy that everyone was still alive— wouldn’t he?

Dr. Levi Roque, who headed the International Rescue Committee’s field team in Pakistan, pointed out that conditions in Afghanistan were now such that vast increases in the refugee population could well occur. (They have.) — Oh, good, said the Young Man to himself; things will get worse, then. (They have.) He settled into the interview with real enjoyment.

“IT WILL TAKE A LONG, LONG TIME”

“No amount of medicine can cure them, ” Levi said. “We have to educate them. But how? That remains to be seen; it will take a long, long time. That is why we are starting on this wash-your-hands, cut-your-fingernails business. Why is it important that you wash your hands and cut your fingernails? These are the things that they have to learn right now. We are trying our best to do it.”

“How often would you say that refugees ask for medicines that they don’t need? ”

“They don’t ask for things they don’t need, ” said Levi wryly. “They just ask for everything, whether they need it or not. ‘Give me the white pill. Give me this yellow.’ Give me this, give me that. — Oh, I’ll give you an example. We’re doing family planning. We have these contraceptive pills. So. One of these men got hold of our contraceptive pill, because it comes in pink color. And he’s taking it, because he loves the color! ” —He laughed. — “I hope he don’t get pregnant.”

The Young Man remembered something that Levi had told him earlier. “Do any of them still hold your medical teams at gunpoint? ”

“Well, not anymore, ” Levi said. “But they always say, ‘All of this medicine belong to us anyway; give us all this! ’ But when we give them proper explanation, they say okay. They are stubborn, but they listen … In here, well, the Afghans are lazy. They do not want to help themselves. The Indochinese refugees, they work very hard for themselves. Here, ” Levi chuckled, “they don’t help you. You pay them, they help you.”

“What do you think the best thing the Americans could do for the refugees would be? ”

“I really don’t know, ” Levi said. “Well, the Americans are giving a lot of food, and I think they should keep it up.† Why? Well, now we are facing so many Afghans already in Pakistan. If we can keep them healthy, that’s a very good sign; that’s very good. We have to anticipate that those Afghans in Afghanistan, in which, in the long run, there might — who knows? — be an emergency, they will cross Afghanistan like the Kampucheans and be dying of hunger. Then we face only one problem — that one, because we keep the refugees here healthy. So that is why, I hope, a lot of people will give more.”

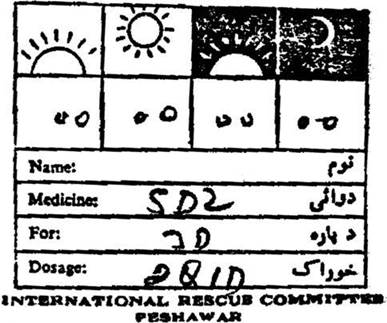

Prescription form for illiterate refugees, the dosage and timing being indicated by the number of pill-symbols blackened and the sun positions.