Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

The Decision

|

|

Nucor started to scan its environment for thin-slab casting technology in 1983, a year after experiencing its first sales decline under Iverson. The initial search turned up a number of relevant projects but none seemed to be ripe for commercialization. SMS, which had supplied casting equipment to Nucor since it built its first steel mill at Darlington, approached Nucor in the summer of 1984 with the CSP concept but Iverson concluded that while it looked good on paper, it was still in an embryonic stage. Nucor ordered a Hazelett thin-slab caster instead and began to experiment with it at Darlington.

Nucor spent $6 million on its Hazelett caster through 1986 and developed a special nozzle for pouring steel into it that reduced turbulence. But over the course of the year, it became increasingly interested in CSP. SMS had returned in early 1986 with fresh performance-data on its pilot CSP plant. Iverson recalled that these data impressed him and others because they improved on the company's own development effort. COO Aycock and top engineering and operations people from individual plants went to Germany in the spring of 1986 to take a closer look and were very enthusiastic when they returned. While uncertainties remained and some felt that SMS should be encouraged to resolve them by performing another round of experiments with a pilot plant of industrial scale, most members of the team agreed that CSP had more potential than other thin-slab casting techniques. " The most important aspect, " concluded Iverson at the time, " is that we have seen nothing about the concept that tells us it is not viable."

In the summer of 1986, Iverson asked project teams from Nucor and SMS to study the feasibility of a CSP plant of commercial scale. The teams focused on denning the prospects for a CSP plant with close to a million tons of capacity at an unspecified site in the Midwest, close to the largest steel and scrap markets in the United States. Although most of the equipment for the plant was to be newly built, SMS located a second-hand cold-rolling mill in West Germany that was available for $1 million and could be renovated for $10 million. The evaluation of the prospects for a CSP plant with this configuration was anchored in the fact that Nucor had already used engineering companies' quotes for equipment and cost projections based on recent plants to put together a construction budget and profit-and-loss statements for a plant employing Hazelett casting. In order to assess the prospects for a plant based on a different thin-slab casting technique, it seemed sensible to begin by revising existing cost estimates for just that component of the project.

Nucor thought that as the first adopter of CSP, it might be able to secure a $10-$20 million discount off the $90 million SMS was asking as the supplier of core machinery and technical support. It would also try to make some of its payments to SMS contingent on performance clauses. Based on prior analyses, these assumptions and basic engineering by SMS, it appeared that the CSP plant would cost Nucor $280 million in total, take two-and-a-half years to complete, and two more years to reach rated production capacity. Nucor also projected the plant's start-up costs and working capital requirements to be an additional $30 million each. Its steady-state operating costs would be driven by the price of scrap and the level of labor productivity. Nucor felt fairly comfortable with its first-cut estimates of operating costs, less so with its construction cost estimates and least of all with start-up cost estimates. Exhibit 12 summarizes a leading industry consultant's calculations of the construction and operating costs Nucor could expect to incur and compares them to estimates for a modernized integrated mill and an unmodernized one it might compete against in the flat-sheet segment.

Iverson was aware of this economic information. He also knew that the Nucor project team that prepared it was eager to proceed with the CSP plant. SMS had devoted six months to basic project engineering and was bound to press him for a commitment at the meeting that was about to begin. Iverson felt that it was time to make a decision. While he felt generally positive about CSP, he continued to wrestle with several issues.

First, pioneering the commercialization of a new technology was likely to entail " unknown. unknowns" and to lead therefore to pioneering costs. Would the benefits of being the first adopter offset them? It was clear that Nucor could not lock up CSP by moving first: SMS owned the technology, was interested in diffusing it more broadly and would insist on the rights to observe process improvements at Nucor's plant and to show them off to prospective customers. Other minimills were known to be interested in CSP. Nucor might gain only a two-to-three year head start by being the first adopter if others decided to be fast followers. In addition, widespread adoption of CSP by other minimills intent on entering the flat-rolled segment might significantly increase the price of premium scrap. If scrap prices rose above $140 per ton, however, Nucor could probably shift to direct reduced iron (DRI, or iron ore that had been reacted with natural gas) as its principal raw material, although that would require substantial changes in its facility and operations.

On the operating side, flat-rolled products presumed steelmaking expertise somewhat different from that required by non-flat products. Additionally, Nucor's policy of locating plants in rural areas might, with a plant larger and more complex than any it had built before, create an overwhelming operational challenge. It was also possible that integrated mills adopting CSP might be able to outpace Nucor on the basis of their cumulated experience at flat-rolled production.

As far as marketing was concerned, Nucor was confident that it would be able to penetrate the low end of the flat-sheet market, which consisted primarily of construction applications, where low price was the key to winning business. Nucor's own Vulcraft division could use about 100, 000 tons of flat sheet each year to produce steel deck. While cheap imports were a force to be reckoned with in external sales to the low end, a measure of protection was provided by the fact that the CSP technology pushed U.S. labor costs down toward the level of ocean freight costs incurred by imports. The high end of the market was a different story. Products such as outer panels for appliances, and bodies and hoods for automobiles would be harder to penetrate because they required superior quality, reliable delivery of large quantities, and relationship-based marketing (including early involvement in product development). Although the first CSP plant's capacity could probably be filled with low-end business, Nucor would also have to target the high end if it brought a second or third plant on stream.

Resource constraints were also a cause for concern. The joint venture with Yamato Kogyo (to produce wide-flange beams) was already agreed upon. If Nucor took on the thin-slab project now the two projects would virtually coincide, stretching the company's financial and managerial resources. Allowing for expected start-up costs, Nucor would have to incur capital expenditures of about $100 million in 1987, $250 million in 1988 and a balance of $60 million or more in 1989 if it pursued both projects simultaneously. With yields on 10-year Treasury Bills and A-rated corporate bonds at 7.26% and 9.41% respectively, the cost of funding both projects would be substantial. Nucor did, however, have $185 million in cash and short-term securities on hand.

Technological leapfrogging was another major worry. While the Hazelett caster did not appear to be as efficient as CSP, other attempts to cast even thinner slabs were under way. For example, one of SMS's leading competitors, Mannesman-Demag, was promoting a process that would cast slabs that were only one inch thick—thin enough to be coiled and, consequently, to permit the decoupling of the casting stage from the rolling stage. Longer term, it was clear that thin-slab casting represented a step toward the ultimate goal of direct casting of sheet and strip. Did it make sense to invest in the former, knowing that it might become obsolete in 10 - 12 years? Although Iverson thought of these years as a window of opportunity, was the window wide enough to justify a full-scale strategic commitment to CSP?

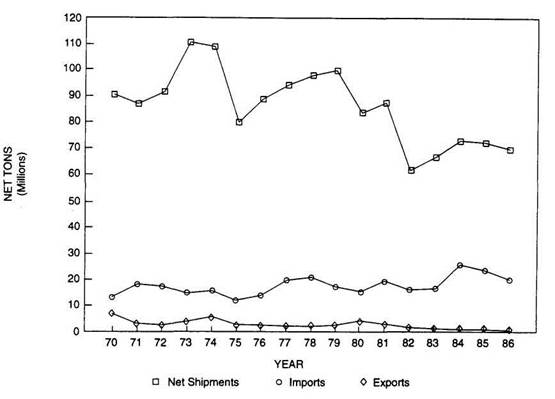

Exhibit 1 Net U.S. Shipments, Exports and Imports: 1970-1986*

Source: American Iron and Steel Institute, Annual Statistical Report, various years.

*Net shipments - exports + imports = apparent steel consumption.

Exhibit 2. Steel Mill Product Segments: 1986

| Product | Tons | Percent |

| Ingots, Billets, Slabs | 1 388 649 | 1, 9 |

| Plates | 3 531 806 | 5, 1 |

| Sheet - Hot Rolled | 11 993 239 | 17, 2 |

| - Cold Rolled | 13 106 656 | 18, 8 |

| - Coated and Strip | 11 148 806 | 16, 0 |

| TOTAL FLAT SHEETS | 36 248 701 | 52, 0 |

| Bars | 12 101 713 | 17, 4 |

| Structural Shapes | 4 520 713 | 6, 5 |

| Wire Rod and Wire Products | 4 573 954 | 6, 6 |

| Pipe and Tubing | 2 836 458 | 4, 1 |

| Other | 4 442 140 | 6, 4 |

| TOTAL SHIPMENTS | 69 644 134 | 100, 0 |

| Source: American Iron and Steel Institute, 1986 Annual Statistical Report. |

|

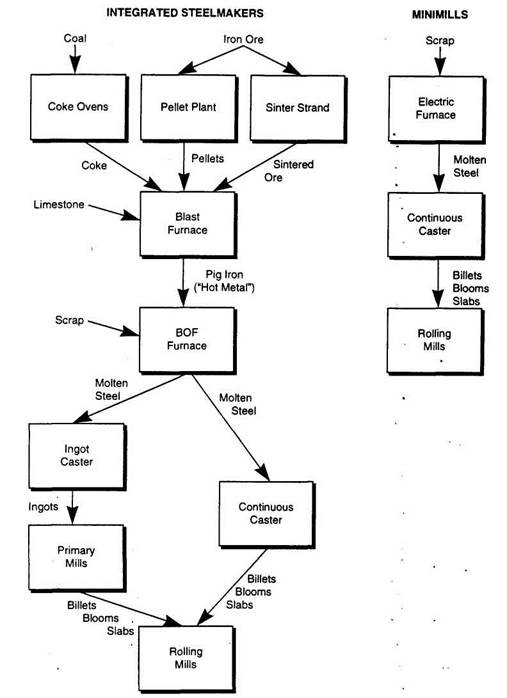

Exhibit 3 Steel Production Processes

Source: Donald F. Barnett and Robert W. Crandall, Up from the Ashes: The Rise of the Steel Minimill in the United States (Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1986): 4. © 1986 The Brookings Institution.

Exhibit 4 Capacity Incorporating New Technologies (in %)

| United States | Japan | E.C. | Canada | |

| BASIC OXYGEN FURNACE | ||||

| 3, 4 | 11, 9 | 1, 6 | 28, 1 | |

| 17, 4 | 55, 0 | 19, 4 | 32, 3 | |

| 48, 1 | 79, 1 | 42, 9 | 31, 1 | |

| 61, 6 | 82, 5 | 63, 3 | 56, 1 | |

| 60, 6 | 75, 2 | 75, 1 | 58, 6 | |

| BASIC OXYGEN FURNACE PLUS ELECTRIC FURNACE | ||||

| 11, 8 | 32, 0 | 11, 5 | 40, 4 | |

| 27, 9 | 75, 3 | 31, 5 | 45, 1 | |

| 63, 5 | 95, 9 | 57, 7 | 45, 9 | |

| 81, 0 | 98, 9 | 82, 6 | 76, 4 | |

| 88, 8 | 100, 0 | 98, 6 | 86, 5 | |

| CONTINUOUS CASTING | ||||

| 4, 8 | 11, 2 | 4, 8 | 11, 5 | |

| 10, 5 | 35, 0 | 20, 1 | 12, 0 | |

| 21, 1 | 70, 7 | 45, 1 | 32, 2 |

Source: Donald F. Barnett and Louis Schorsch, Steel: Upheaval in a Basic Industry (Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger, 1983): 55.

Exhibit 5 Summary Data for Three Largest Integrated U.S. Steelmakers: 1986

| USX | LTV | Bethlehem | |

| Flat-rolling capacity (millions tons year) | 12, 4 | 12, 3 | 6, 5 |

| Number of flat rolling rlants | |||

| Total steelmaking capacity (millions tons year) | 26, 0 | 18, 0 | 16, 0 |

| Total number of mills | |||

| Capacity utilization (%) | 36, 6 | 60, 5 | 65, 1 |

| Continuous casting (%) | 26, 5 | 31, 0 | 58, 3 |

| Steel-related sales ($ billions) | 3, 7 | 4, 5 | 4, 1 |

| Steel-related income ($ billions) | (1, 37) | 0, 10 | (0, 11) |

| Total sales ($ billions) | 14, 9 | 7, 3 | 4, 3 |

| Net income ($ billions) | (1, 83) | (3, 25) | (0, 15) |

| Long-term debt-to-equity ratio (%) | 50, 0 | 74, 0* | 65, 0 |

| Steel sales by customer group (%) | |||

| —Automotive | 10, 5 | 28, 0 | 23, 7 |

| —Construction | 12, 4 | 9, 0 | 20, 0 |

| —Service Centers | 31, 8 | 34, 0 | 38, 1 |

Source: Annual Reports and 10K reports.

*These figures are for 1985. In 1986, LTV filed for bankruptcy. Its unsecured debts of ($2, 316 billion) were classified as pre-petition liabilities pursuant to Chapter 11 proceedings. Secured long-term debt amounted to $108 million. The book value of LTV's equity in 1986 was ($2, 843 billion).

Exhibit 6 Summary Data on Nucor Corporation: 1972-1986

| A) OPERATIONS | |||||||||||||||

| Total number of plants | |||||||||||||||

| Steel capacity (000 tons) | |||||||||||||||

| Steel production (000 tons) | |||||||||||||||

| Employees | |||||||||||||||

| Man hours per ton | 4, 9 | 4, 9 | 4, 7 | 4, 6 | 4, 4 | 4, 1 | 3, 9 | 3, 7 | 3, 3 | 3, 0 | 2, 9 | 2, 7 | 2, 6 | 2, 5 | 2, 4 |

| B) FINANCIALS (thousand of dollars) | |||||||||||||||

| Sales* | |||||||||||||||

| COGS | |||||||||||||||

| SG4A | |||||||||||||||

| Interest expense | (1220) | (749) | (3959) | (7561) | (5289) | ||||||||||

| Taxes | |||||||||||||||

| Net earnings | |||||||||||||||

| Capital expenditures * | |||||||||||||||

| Depredation | |||||||||||||||

| Current assets | |||||||||||||||

| Total assets | |||||||||||||||

| Current liabilities | |||||||||||||||

| Long-term debt | |||||||||||||||

| Stockholders' equity | |||||||||||||||

| Shares outstanding | |||||||||||||||

| Average stock price | $2, 20 | $1, 86 | $1, 69 | $168 | $2, 58 | $3, 32 | $5, 59 | $10, 12 | $17, 38 | $21, 88 | $16, 27 | $24, 30 | $23, 42 | $28, 92 | $37, 65 |

| Producer price Index tor metals and metal products | 39, 6 | 42, 6 | 55, 2 | 59, 6 | 63, 0 | 67, 2 | 73, 0 | 83, 3 | 92, 1 | 96, 9 | 98, 6 | 101, 6 | 101, 2 | 100, 0 |

Source: Nucor Annual Reports, various years.

*Figure includes sales of the finished steel products listed in Exhibit 9 and should not, therefore, be attributed entirely to steel production.