Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Measuring the degree of individualism in society

|

|

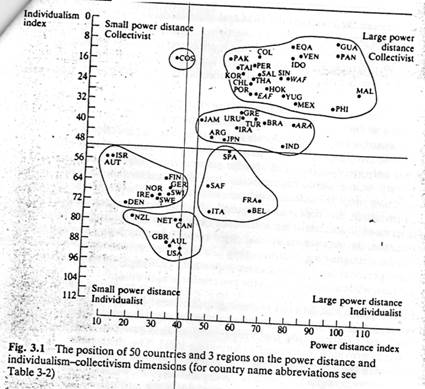

Extreme collectivism and extreme individualism can be considered as the opposite poles of a second global dimension of national cultures, after power distance which was described in Chapter 2. All countries in the IBM studies could be given an individualism index score which was low for collectivist and high for individualist societies.

The new dimension is defined as follows.

Individualism pertains to societies in which the ties between individuals are loose: everyone is expected to look after himself or herself and his or her immediate family.

Collectivism as its opposite pertains to societies in which people from birth onwards are integrated into strong, cohesive ingroups, which throughout people's lifetime continue to protect them in exchange for unquestioning loyalty.

Degrees of individualism obviously vary within countries as well as between them, so it is again very important to base the country scores on comparable samples from one country to another. The IBM samples offered this comparability.

The survey questions on which the individualism index is based belong to a set of fourteen 'work goals'. People were asked: 'Try to think of those factors which would be important to you in an ideal job; disregard the extent to which they are contained in your present job. How important is it to you to...' followed by 14 items, each to be scored on a scale from 1 (of utmost importance to me) to 5 (of very little or no importance). When the answer patterns for the respondents from 40 countries on the 14 items were analyzed they reflected two underlying dimensions. One was individualism versus collectivism. The other came to be " labeled' masculinity Versus femininity (see Chapter 4).

The dimension to be identified with individualism versus collectivism was most strongly associated with the relative importance attached to the following 'work goal' items. For the individualist pole:

1. Personal time Have a job which leaves you sufficient time for your personal or family life.

2. Freedom Have considerable freedom to adopt your own approach to the job.

3. Challenge Have challenging work to do — work from which you can achieve a personal sense of accomplishment.

For the opposite, collectivist pole:

4. Training Have training opportunities (to improve your skills or learn new skills).

5. Physical conditions Have good physical working conditions (good ventilation and lighting, adequate work space, etc.).

6. Use of skills Fully use your skills and abilities on the job.

If the IBM employees in a country scored work goal (1) as relatively important, they generally also scored (2) and (3) as important, but (4), (5), and (6) as unimportant. Such a country was considered individualist. If (1) was scored as relatively unimportant, the same generally held for (2) and (3), but (4), (5), and (6) would be scored as relatively more important. Such a country was considered collectivist.

Obviously, these items from the IBM questionnaire do not totally cover the distinction between individualism and collectivism in a society. They only represent the issues in the IBM research which relate to this distinction. The correlations of the IBM Individualism country scores with non-IBM data about other characteristics of societies confirm (validate) the claim that this dimension from the IBM data does, indeed, measure individualism.

In itself, it is not difficult to identify the importance of personal time, freedom, and (personal) challenge with individualism: they all stress the employee's independence from the organization. The work goals at the opposite pole: training, physical conditions, and skills being used on the job refer to things the organization does for the employee, and in this way stress the employee's dependence on the organization which fits with collectivism. Another link in the relationship is that, as will be shown, individualist countries tend to be rich and collectivist countries poor. In rich countries training, physical conditions, and the use of skills may be taken for granted V which makes them relatively unimportant as work goals. In poor countries these things cannot be taken for granted: they are essential in distinguishing a good job from a bad one, which makes them quite important among one's work goals.

The actual calculation of the individualism index is not, as in the case о power distance, based on simply adding or subtracting question scores after multiplying them by a fixed number. The statistical procedure used to identify the Individualism, and, in Chapter 4, the masculinity dimension о the basis of the 14 work goals produces automatically a factor score for either dimension for each country. These factor scores are a more accurate measure of that country's position on the dimension than could be obtained by adding or subtracting question scores. The factor scores for the individualism dimension were multiplied by 25 and a constant number of 50 points was added. This puts all scores in a range from close to 0 for the most collectivist country to close to 100 for the most individualist one1.

| Table 3.1 Individualism index (IDV) values for 50 countries and 3 regions | |||||

| Score rank | Country or region | IDV score | Score rank | Country or region | IDV score |

| USA | Turkey | ||||

| Australia | Uruguay | ||||

| Great Britain | Greece | ||||

| 4/5 | Canada | Philippins | |||

| 4/5 | Netherlands | Mexico | |||

| New Zealand | 33/35 | East Africa | |||

| Italy | 33/35 | Yugoslavia | |||

| Belgium | 33/35 | Portugal | |||

| Denmark | Malaysia | ||||

| 10/11 | Sweden | Hong Kong | |||

| 10/11 | France | Chile | |||

| Ireland (Republic of) | 39/41 | West Africa | |||

| Norway | 39/41 | Singapore | |||

| Switzerland | 39/41 | Thailand | |||

| Germany F. R. | Salvador | ||||

| South Africa | South Korea | ||||

| Finland | Taiwan | ||||

| Austria | Peru | ||||

| Israel | Costa Rica | ||||

| Spain | 47/48 | Pakistan | |||

| India | 47/48 | Indonesia | |||

| 22/23 | Japan | Colombia | |||

| 22/23 | Argentina | Venezuela | |||

| Iran | Panama | ||||

| Jamaica | Equador | ||||

| 26/27 | Brazil | Guatemala | |||

| 26/27 | Arab countries |

The individualism index (IDV) scores can be read from Table 3.1. As in the case of the PDI in Chapter 2 the scores represent the relative positions of countries. What can immediately be recognized by inspecting Table 3.1 is that nearly all wealthy countries score high on IDV while nearly all poor countries score low. There is a strong relationship between a country's national wealth and the degree of individualism in its culture; it will be further explored later in this chapter

Sweden scores 71 on IDV and the group of Arab-speaking countries to which Saudi Arabia belongs scores an average of 38, which demonstrates the cultural roots of Johannesson's dilemma. Of course the Arab countries differ among themselves, and impressionistically the Saudis within this region are even more collectivist than some other Arabs like Lebanese or Egyptians. In the IBM sample the latter were more strongly represented than the Saudis. Sweden's rank among 53 countries and regions is 10-11 and the Arab countries' rank 26-27, so there are still a lot of countries scoring more than the Arab average. As stated above, collectivism is the rule in our world, and individualism the exception.

Sweden scores 71 on IDV and the group of Arab-speaking countries to which Saudi Arabia belongs scores an average of 38, which demonstrates the cultural roots of Johannesson's dilemma. Of course the Arab countries differ among themselves, and impressionistically the Saudis within this region are even more collectivist than some other Arabs like Lebanese or Egyptians. In the IBM sample the latter were more strongly represented than the Saudis. Sweden's rank among 53 countries and regions is 10-11 and the Arab countries' rank 26-27, so there are still a lot of countries scoring more than the Arab average. As stated above, collectivism is the rule in our world, and individualism the exception.