Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Library Architecture

|

|

Library Architecture is concerned with bringing together in agreeable, convenient and practical surroundings great number of books and readers, efficiently served by a library staff. It's a modern problem. The world has long had library materials to use and store, but it was not until after the development of the rotary press in the mid-19th century that the vast quantities of books made new methods essential. Prior to this time, it was practical to have one large room or gallery for both books and readers. Books were kept in shelves or

cupboards with suitable furniture on which the heavy volumes could be rested. Aesthetically the treatment of these rooms was often masterful, as in the Vatican or the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence. To meet the challenge of the printing press, reading rooms were, at first, made larger with added tiers of books and galleries, but limits of expansion for a single gallery were soon reached, and some method had to be devised for separating the public in reading rooms from the room for storing books.

cupboards with suitable furniture on which the heavy volumes could be rested. Aesthetically the treatment of these rooms was often masterful, as in the Vatican or the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence. To meet the challenge of the printing press, reading rooms were, at first, made larger with added tiers of books and galleries, but limits of expansion for a single gallery were soon reached, and some method had to be devised for separating the public in reading rooms from the room for storing books.

As early as 1835. the French architect, Benjamin Delessert, suggested for the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris a circular reading room with bookstacks surrounding it. This circular reading room allowed librarians (installed on a raised platform in the centre) easier supervision of the readers. Delessert's plan probably suggested that of the reading room of the British museum (R. & S. Smirke, architects, 1852).

When Henri Labrouste was appointed architect of the new Ste. Genevieve library in Paris (1843). the site selected, being long and narrow, almost forced the solution. A reading room occupied the entire upper floor of the building and contained many of the books, as in the old libraries, but other spaces were made for books on the floor beneath, a scheme that in subsequent years was used in many important libraries. Significant was the separation of books and readers.

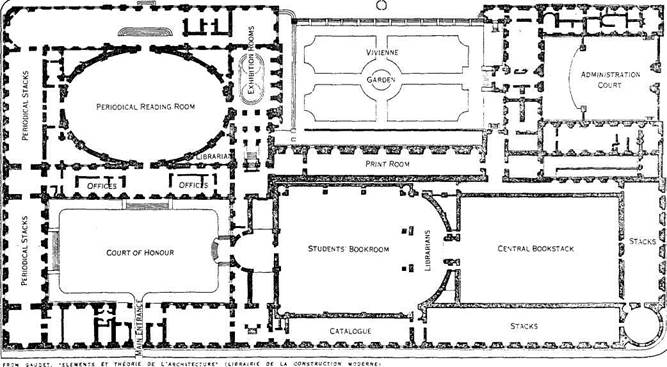

Later, in the plans for the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris (1854), where he was less hampered by the exigencies of space, Labrouste designed another remarkable building. The main reading room is square, with an apse where the librarians are installed facing its entrance and commanding that to the stacks. The reading room is surrounded by three tiers of shelves. The light comes through a large opening on the north side, and from nine domes, each of which rests on four light steel columns. The atmosphere of the room is quiet and restful and the light is excellent. The most remarkable part of the composition, however, is the book-stack, a huge room, 90 ft. x 120 ft. Here the principle of the modern bookstack first evolved. The shell of masonry is covered by a glass skylight which allows daylight to penetrate every corner, while inside this shell the metal framework of the book tiers and the passages between are entirely independent construction resting on the basement floor.

Library Planning.—The three types of library plans, represented by the Ste. Genevieve, the Bibliotheque Nationale of La-

brouste and the British museum, furnished the patterns for most large libraries of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. To the type of Ste. Genevieve; i.e., with a reading room lighted on both sides, with books along the walls or in alc oves and with storage under the reading room, belongs the New York Public library (Carrere and Hastings, architects, 1897). To the type of the Bib-liotheque Nationale; i.e., with a reading room parallel or perpendicular to the stacks, belongs the Widener Memorial library at Harvard. To the type of the British museum; i.e., with a circular reading room, surrounded by the bookstacks and lighted by high windows or skylights, belong the old Columbia University library. New York (McKim, Mead & White, architects, 1897). and the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (Smithmeyer, Pelz & Casey, architects. 1886-97).

A marked progress in library design was noticeable around 1930. In particular, the Municipal library at Viipuri (Viborg) (1934, Alvar Aalto, architect) incorporated many of the newer ideas in a relatively small building. Here the technical requirements for shadowless lighting, mechanical ventilation and acoustical treatment influenced the shape of rooms and contributed the interest in the wall and ceiling surfaces formerly supplied by surface decoration.

The storage annex at Versailles of the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris provided one solution to the problem caused by the accumulation and growth of material to be stored by libraries, in this case a separate building outside the city. Discussions at the library congress held in Paris in 1937 led to the system of reduction of certain material by photography (newspapers for example) onto 35 mm. film as a method of saving space. Microprinting is a further development of this idea. Branch libraries and reference libraries specializing in particular fields tend to overcome the un-wieldiness of huge central libraries.

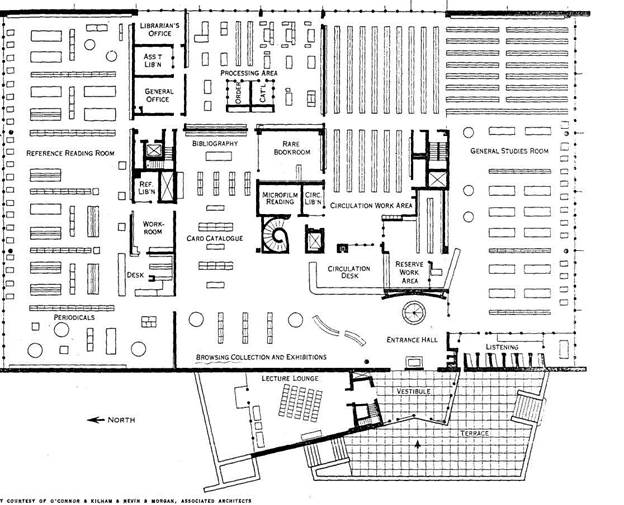

U.S. Libraries.—In the United States numbers of people began to borrow books for home reading. This gave rise to a further service, the essential feature of which was the delivery room with its desk in direct communication with the stacks, and its catalogues and open shelves so arranged that readers in the reading rooms were not disturbed by users. In the larger libraries, the increased size of the card catalogue required a special room. In the New York Public library, for example, the catalogue room is on the third floor and readers pass through it on the way to the

Fig 1.—first floor plan of the bibliotheque nationale. Paris

Fig 1.—first floor plan of the bibliotheque nationale. Paris

|

| 4 _____ ш в Р0 |

FIG. 2.—MAIN FLOOR PLAN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE (KY.) LIBRARY

FIG. 2.—MAIN FLOOR PLAN OF THE UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE (KY.) LIBRARY

|