Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

James Harrison

|

|

Harrison was the publisher of the Geelong Advertiser and it was while cleaning type with ether (эфир) that he made his discovery. He noticed that as the ether evaporated it made the metal cold and realised that he could use this phenomenon (that gases cool as they expand, which was what was happening when the ether evaporated) to make ice. Harrison designed a machine that by 1857 was producing 3 tonnes of ice a day.

Unfortunately, people were reluctant to buy Harrison's ice, claiming that they preferred the 'natural' product. He was declared bankrupt, and was forced to sell his newspaper in 1860. After his move to Melbourne, Harrison turned his attention to the problem of sending surplus Australian meat to Britain. Refrigeration was obviously the answer, and in 1873 Harrison arranged for a shipment of meat to be sent to England aboard the sailing ship Norfolk, fitted with his ether cooling system. The project ended in disaster. The meat was ruined for reasons beyond Harrison's control, and he returned penniless to Britain to work as a journalist. It was to be another six years before Harrison's dream was realised, and the first cargo of Australian frozen meat arrived safely in England using another refrigeration system.

First tank: good invention, bad timing

Shortly after the outbreak of World War I it became clear that a new type of fighting vehicle was needed to cope with the trenches, machine guns, barbed wire and mud.

In 1915, both France and Britain began experiments with tracked (на гусеничном ходу) armored (бронированный) fighting vehicles, which led to the appearance of the first tank, nicknamed " Mother", in Britain in February 1916.

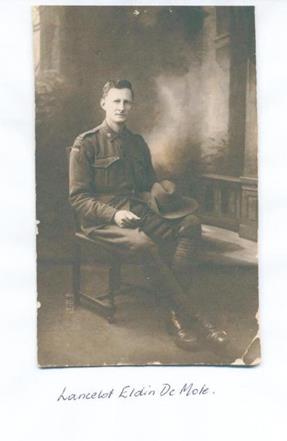

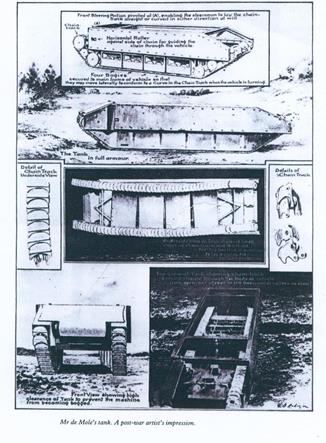

In fact, plans for a vehicle very similar to 'Mother' had been sent to the War Office in

London by Adelaide engineer Lancelot de Mole in 1912. At that time, however, the War Office was unable to foresee a future for de Mole's invention, and so it was rejected. After the war, de Mole put in a claim for royalties, but he had to be content with an acknowledgment from the British Royal Commission for Awards, which investigated his claims and recognized that he had produced a '… brilliant invention which anticipated, and in some respects surpassed that actually put into use in the year 1916'.