Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

The Darktown strutters on Broadway

|

|

(p. 149 - 158)

ANYONE so minded can write an entirely false history of American civilization by setting down in parallel columns the vogues and rages which have overtaken us and Europe at the same time. The highly patriotic, but a bit undergraduate, habit of slanging your own country is always more effective if the facts about any other country are a little obscure, and, thanks to the cable and the efficacy of transatlantic mails, we now know virtually everything that isn't so, and virtually nothing that is important, about Europe. So it is quite possible for a critic to say that in literature the taste of Europe is far beyond ours, on the ground that Harold Bell Wright is the typical American author and Conrad and Anatole, France and Tolstoi the typical European. I mean that this is possible if a critic has never heard of the work of Nat Gould and William Le Queux in England, for instance.

The latest of these false parallels would be this: that while Europe was going in for the primitive sculpture of the African negro, America devoted itself and its theatres to musical shows composed and produced by the nonprimitive negroes of Harlem, New York.' The wail of the saxophone in Shuffle

[1]This review appeared in Vanity Fair sometime in the summer of 1922. 1 allow it to stand with nothing more than verbal corrections in spite of my dislike of books which collect articles expressly written for magazine publication, because I fe el that the negro show is extraordi-

[149]

Along had not yet died in my ears when a Serious Critic made moan in his journal that the authors of that piece were truckling to the white man's sense of superiority by exhibiting their own flesh and blood as a pack of cheats and scoundrels. What had im pressed me as a fairly awkward mechanism for introducing songs and dances was by him taken as a libel on a race; and forgetting the picaresque romance from the Odyssey to Get-Rich-QuickWallingford, forgetting that all peoples seem to take an abundant pleasure in exposing themselves as delightful rogues, he wept over this degradation. At about that time Mr Clive Bell, marking a reaction from the extreme vogue of African plastic, still ranked the sculptures produced by savage and semicivilized negroes as only a little below those of the two or three great periods of artistic production. Again it would seem that Europe had, in its effete way, stolen a march on us.

In effect the coloured shows were entertaining and

narily transient and that a transient criticism of it is adequate. The permanent qualities are touched on elsewhere; especially in the essay entitled " Toujours Jazz." Since this was written there have been other negro shows, and I have heard that one was better than Shuffle Along. What has interested me more is the report that there is a " nigger show by white men" which is standing them up every night. This verifies a prediction made below-that the negro show would have an effect on the white man's. I am not at all sure that there will not continue to be negro shows for a long time-why in Heaven's name shouldn't there be! They have their qualities and their great virtues. It is only in relation to the sophisticated Broadway piece that I find them lack ing; and have perhaps not been fair enough to them.

[150]

interesting to think about, whether they were good or bad, and most of them were pretty bad. As shows, that is. As shows in a country which really knows how to produce soul-satisfying eye-and-ear entertainment. They had certain attractive qualities, and i f they were in essence second rate, they were at least dynamic, while the first-rate thing in Europe was static. While Europe remained calm after the war we, hysterically, went in for an enormous increase of pace in the active arts of the theatre. I do no t know whether we are altogether the losers, and leave the question to others. I do know that for a moment these pieces seem to have overshadowed our (can I say?) native revues.

Of course, in America no one cares for revues except the unenlightened millions who pay to see them, so there is no one to rise and make lamentation over this state of affairs. For years we have laboured to perfect our revues-and the shuffling feet of a b arbarian summon up an evil jinn to banish them. The serene smoothness of manoeuvre which Mr Wayburn prepares for Mr Ziegfeld shrinks from the boards before the haphazard leaping of unstudied numbers; the sweet gravity of the dancers is forgotten for the b arbarous rhythm of any half dozen darkies with a sense of syncopation innate in them. Lavishness from Joseph Urban precariously maintains itself against the smudged back-drop and the overall; and over the prostrate and flowerlike and seductive

[151]

beauty of the chorus-girl, there steps and struts, magnificently struts, the high-yaller!

The comparatively sober truth is that the negro, cabaret in the theatre is only a diversion, a necessary and healthful variation from our norm. It has qualities seldom exquisite and always arresting; and these qualities, having slowly vanished from the re vue, have found themselves again in burlesque and in these exotics. And I think it highly probable that their only lasting effect will be to restore certain highly desirable things to revue and musical comedy. If there is any doubt of their goodness, anot her contrast will prove the point.

The one claim never made for the negro shows is that they are artistic. Set beside them, then, a professedly artistic revue, the Pinwheel, compounded of native and exotic effects. It had two or three interesting or exciting numbers; but the whole e ffect was one of dreariness. The pall of art was upon it; it died nightly. And Shuge Along, without art, but with tremendous vitality, not only lived through the night, but dragged provincial New Yorkers to a midnight show as well. Facing the other way, one beholds a straight fake, the untimely efforts of Messrs McIntyre and Heath, who served only to remind us that in time since overpast the real nigger show, as practised by Williams and Walker, existed, and that what we are seeing now is actually a continuation thereof, brought down from Harlem to Broadway.

[152]

Now it was fairly obvious that Shuge Along had been conceived as an entertainment for negroes; that is why it remained solid when it took Broadway, to the intense surprise of its producers. It was, in short, an exotic for us, but it wasn't an exoti c for themselves. Its honesty was its success, and its honesty put a certain stamp upon its successors. In all of them there is visible a regrettable tendency to imitate, at moments, the worst features of our usual musical comedy. But the major portion of each show is native, and so good.

They have all of them an appearance of unpremeditated violence which distinguishes them from the calculated and beautiful effects of Mr Ziegfeld or Mr John Murray Anderson. It goes much beyond the celebrated (and by this time faked) appearance of " enjoyin g themselves." They may never forgive me for it, but I really do not care whether the actors and actresses who amuse me are having a good time themselves. The theatre, for them, is a place for producing, not for enjoying sensations and effec ts; so the one thing I wish them is that when they are good they may have the purely moral pleasure of being good. It is the method that counts, and in the negro shows the method has been always the maximum pressure in song and dance, and the minimum of s ubtlety in the conversations and patter songs. The exceptions are not notable.

The songs and dances must be scored fff, a stretto,

[153]

and after that those diverging lines which indicate crescendo; the lines of violence never again approach each other in these numbers, and one has to wait for the appearance of a fairly silly sentimental song for a moment of quiet. The strange peop le who direct these shows and the responsive animals who sing and dance have with some success controverted the notion that it is in contrasts that the intelligent man has his greatest pleasure. One feels that the show is a continuous wild cry and an unin terrupted joyous rage, that the elan vital is inexhaustible and unbridled and enormously good.

The most skilful individual player has been Florence Mills; merely to watch her walk out upon the stage, with her long, free stride and her superb, shameless swing, is an aesthetic pleasure; she is a school and exemplar of carriage and deportment; two oth er actors I have seen so take a stage; Cohan by stage instinct, Marie Tempest by a cultivated genius. Florence Mills is almost the definition of the romantic " une force qui va, ' but she remains an original, with little or nothing to give beyond her presence, her instinctive grace, and her baffling, seductive voice. Without that endowment, a small one in comparison with, say, Gilda Grey's, almost all the others give nothing but energy, and the trouble there is that if you have nothing but energy to give, you must give more than you can afford. The wild cry is a little too piercing at times, the postures and the pattings and

[154]

the leapings, all a little beyond the necessary measure. It remains simple; but simplicity, even if it isn't usually vulgar, can be a bit rough.

In the past few years the line of development of most of our revues and musical shows has been clearly marked; the bad old days were slowly forgotten and whatever was suggestive had to become subtle; and gradually, as the surface polish grew brighter, the suggestive humours underneath were forgotten; our revues became denatured in more senses than one. There is one risque' moment in the whole of a recent Follies, and that is one more than usual. The twittering about love and a kiss goes on; but the Great Reality of Sex is (quite properly, I am sure) forgotten. And in an encore stanza of He May Be Your Man, But He Comes to See Me-Sometimes, as sung at the Plantation, the whole conventionalized fabric of our popular love songs was flung aside and the gay reality exposed. This amorous frankness is part of a simple realism - a sophisticated realism couldn't occur in a musical show, unless in the manner of Offenbach's La Belle Helene. It is a fitting counterpart to the exaggerated p ostures, the slightly lubricious gestures and movements, of the dance. Another simplicity, and a very good one, is in such a song as that about a dog from Tennessee in Oh, Joy - a song which with that one quality, and against indifferent music and unexcep tional words, broke up the show.

[155]

Behind the frankness and the violence and the simplicity there is found the most important factor of all-the music. And behind that stands a figure exceedingly attractive and, in its tragedy, almost moving, that of the late Jim Europe. Of the music itself -of jazz and the use of spirituals and the whole question of our national music-this is clearly not the place to write. One wishes to mention a name or two: Shelton Brooks, least habile of pseudo-Balieffs, wrote long ago The Darktown Strutters' Ball, which ought not to be forgotten; Creamer and Layton composed all of Strut, Miss Lizzie, and therein appeared Sweet Angeline, as complex a piece of syncopation as Mr Berlin ever composed. What portion of Shuffle Along was composed by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake I do not know, but Sissle in action and Blake at the piano were wholly satisfying and expert. And all of these composers, and all of the jazz bands who play for them, have the ineffable advantage of being assur ed, in advance, of dancers who in fancy or straight dancing have the essential feelings for rhythm and broken rhythm in their bones.

And that interior response to syncopation Jim Europe had to the highest possible degree. He had been, before the war, the band leader at the Castles'; I am told by one who knows of such matters that his actual vogue was passing when the war came. He retur ned with the 369th U. S. Infantry " Hell-Fighters" Band and for a few Sunday nights in March,

[156]

1919, he packed the old Manhattan Opera House to the doors.

Say that what he played had nothing to do with music; say that to mention the name of a conductor in the same breath with his name is an atrocity of taste-- I cannot help believing that Jim Europe had the essential quality of music in him, and that, in hi s field, however far from any other it may have been, he was as great as Karl Muck in his. He did have contrast; it was out of the contracting stresses of a regular beat and a divergent that he created his effects. The hand kept perfect time, and his righ t knee, with a sharp and subtle little motion, stressed the acceleration or retard of the syncope. His dynamics were beautiful because he knew the value of noise and knew how to produce it and how to make it effective; he knew how to keep perfectly a runn ing commentary of wit over the masses of his sound; and the ease and smoothness of his own performance as conductor had all the qualities of greatness. He rebuked a drummer in his band for some infraction of discipline and was killed.

Whatever the negro show has to give to the perfected Broadway production has its sources fairly deep in the negro consciousness, and I put Jim Europe forth as its symbol because in him nearly all that is most precious came to the surface. He seemed sensit ive to the ecstasy and pathos of the spirituals as he was to the ecstasy and joy of jazz. He was,

[157]

as conductor, vigorous and unaffected and clean. In Shuffle Along, Messrs Sissle and Blake paid honour to his memory, but the unacknowledged debt of the others is greater. I am inclined to think that, if sterility does not set in for the more notab le Broadway product, it will be because something of what Jim Europe had to give has been quintessentialized by his successors and adopted.

[158]

PLAN FOR A LYRIC THEATRE IN AMERICA

I AM going to establish a lyric theatre in America. Not an art theatre and not a temple of the drama, and not an experimental theatre. A lyric theatre where there will always be Mozart and Jerome Kern and Gilbert-and-Sullivan and Lehar--and NEVER by any chance Puccini or the Ring or Ibsen. I shall avoid the good things and the bad alike in the seri ous forms; I shall have Russian Ballets and American ballets. The chief thing is that it will be a theatre devoted to all the forms of light musical entertainment and to nothing else. My theatre will put an end to those disheartening revivals (or r esurrections) of popular musical shows because the shows will be kept alive, just as " grand" operas are kept alive by appearing in a repertory. Into the repertory I shall incorporate-as soon as their independent existence is at an end--such successes as The Night Boat and such failures as The Land of Joy. There will never be a chance for fashion to destroy things essentially good. I shall produce new pieces, too; and if they are good they will run along with frequent presentations until they are absorbed in the general scheme. And I think I shall have pas tiches frequently--of revues and topical productions which aren't, as entireties, capable of continuing.

That is the abridgement of a scheme, and I say I shall do it in the hope that someone else, even if it be the Messrs Shubert, will do it instead. Because I like musical comedy and it annoys me that I can

[16l]

hear Un bel di (which I want never to hear again) fifteen times a season, and cannot hear The Sun Shines Brighter or The Ragtime Melodrama ever again. And I know that our present type of musical comedy is so good, so vigorous and snappy, that it tends to kill off its predecessors; a repertory is the only thing; and the usual objections to repertory will fail here, because in this case the devotees of musical shows will know in advance that " it is going to be a good show." I don't know whether the bill should change every day or every week; I feel certain that there ought to be half a dozen centres across the continent, and two or three touring companies. Further details I cannot give now. I shall try to find some means, however, of distinguishing between the second-act finale of The Mottled Mask (" On to the ball at the palace of Prince Gregory") from the second-act finale of The Madcap in Motley (" On to the ball at the palace of Prince Gregory"). It is not part of my scheme to keep bad shows alive.

The rare entertainment such a theatre will afford can be guessed if you look for a moment at the changes in musical shows since l900. We were then coming out of the Gilbert and Sullivan tradition and (after a great vogue of extravaganza) coming into the Viennese mode. It is the fashion now, especially in France, to belittle the Viennese operetta, to call its waltz song heavy and its structure a bore. Possibly these things are true; but Vienna has been

[162]

the home of operetta for over a century and has done well by itself most of the time. Illumination of this predominant influence you can get by going to the Redoutensaal and hearing a performance of The Marriage of Figaro, and within the next few days hearing Die Fledermaus and whatever new piece Lehar or Fall or Oscar Straus has composed. For what one seldom knows from its loftier production is that Figaro is in essence and detail a musical comedy and that almost all we know of the form stems from the combination effected there by a great composer, a fine dramatist, and an exceptionally skilful librettist.1" The imperial ballroom with its tapestried walls, its small stage on which only conventionalized scenery can be set, its divided stairway coming down on the stage, is a setting admirably contrived to give the whole loveliness of operetta. The last scene is in the garden of the count: six boxed trees and moonlight create the effect. And at the last moment, the happy ending, the electric lights are thrown on, the vast crystal chandelier lighting up over the garden, and the event recedes into its real, its secondary framework, as entertainment. One recognizes it for what it is--the gay and exquisite counterpart of grand opera, from which neither the Savoy nor the Viennese operetta ever departed. Musically the Viennese type corresponds more clearly to Italian, the Gilbert and

'For da Ponte's share in the work, cf. Edgar Istel: Das Libretto, which analyzes the changes made in Beaumarchais' play.

[163]

Sullivan to French opera. The absurd conventions of production are taken bodily from the older and more respected type. The same thing is as obviously true in Cimarosa's Marriage Secret as it is in The Chocolate Soldier --the latter being, except for a weaker libretto, a perfect parallel to Figaro. (And nearly as worthy of the perpetual life which is apparently to be denied it.)

It is still unnecessary to describe the Viennese operetta in detail, for immediately after the war it came again into vogue and one or two excellent examples-- The Last Waltz was one of them--re-established some of its ancient prestige. It is at bottom produced for the music. In one the music may be chiefly sung, in another danced. Everything else dé cor, story, humorous episodes--is secondary. Recently an effort has been made to change this. Oscar Straus' Torichte Jungfrau at the Grossesschauspielhaus (Reinhardt's catacombs in Berlin) was all production--and nearly all dreadful. Lehar's latest, Das Gelbe Jacke (not, however, our Yellow Jacket) is entirely in the pure Viennese mode, and the Vienna production (February, 1923) indicates how Viennese operetta is improved in transit to our shores. For our production of musical comedy is almost equal to our production of revue, which is incontestably the finest in the world. With their emphasis on music the Viennese shows naturally centre about the famous waltz-song; and one good waltz has been able

[164]

to make a show a success. Rudolf Friml made a success of High Jinks with a fox-trot.

The English type as we know it, including Caryll and Monckton and Rubens, has had for thirty years the Savoy tradition. This requires a plot of more frivolity than the Viennese, and lyrics of greater humour. The successes have been moderate--" I've got a motto" is no masterpiece. The degree of fun has been higher and the seductiveness of the music less. It was perfectly natural that (with Adele to help them on) a combination of virtues should take place in America in the beautiful Princess Shows of Comstock and Gest, where the talents of P. G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton, and Jerome Kern, stage-managed perfectly by Robert Milton, produced a fresh and attractive type of musical show which for five years progressed in popularity-but had few imitators and suddenly seemed to disappear. It was, in fact, transformed into something else, something good. But one should look at the original closely to discern its exceptional virtues.

Each of the Princess shows had a reasonable, but not serious, plot. The advantage of a plot isn't, as one often hears, that it gives the appearance of reality to the piece, for who should expect that? There is no reason why a musical comedy should not be wholly preposterous, dramatically or psychologically, provided, like Iolanthe, it has a logic of its own. No. The advantage is that when there is a definitely per-

[165]

ceptible structure everything else arrives with greater intensity of effect. The best of the Princess shows had the weakest plot, for Leave It to Jane was based on Ade's College Widow, which has no great quality. Since songs and dances had to take up much time, this plot was gratifyingly reduced to a few essential lines and played without sentiment. The result was a rush of action in which everything found place. The later pieces were on librettos by Guy Bolton, suggesting French farces, and full of neat arrangements. None of them was stupid. They all gave place for Mr. Wodehouse's exceptional talents as a lyric-writer. He is as an English humorist superior to most, and as a master of complicated, original, amusing rhymes is the best man in the business. A special quality of making fun is discernible in all his lyrics, and he does good parodies, like When It's Nesting Time in Flatbush. The Princess type made rather a fetish of simplicity (I quote from memory)

Although the thing that's smart is

To stay out all night on parties,

I'll be sitting, with my knitting,

In the good old-fashioned way,

and of sentiment:

The breeze in the trees brings a scent of orange blossoms

And the skies turn soft and blue,

When there's no one around except the girl you love

And the girl you love loves you,

[166]

which was often not amorous and rose to as fine a thing as The Siren Song:

Come to us, we've waited so long for you,

Every day we make a new song for you;

Come, come, to us, we love you so.

Leave behind the world and its fretting

And we will give you rest and forgetting,

So sang the sirens ages and ages ago.

There was also patter as in the Cleopatra song:

And when she tired, as girls will do,

Of Bill or Jack or Jim,

The time had come, his friends all knew,

To say good-by to him.

She would not stand by any means

Regretful, stormy, farewell scenes,

To such low stuff she would not stoop

So she just put poison in the soup.

When out with Cleopatterer

Men always made their wills;

They knew they had no time to waste.

When the gumbo had that funny taste

They'd take her hand and squeeze it

And murmur, " Oh, you kid! "

But they none of 'em liked to start to feed

Till Cleopatterer did.

and in each of these types Wodehouse was faultless.

Fortunately for him and for us these songs were set to a music which in addition to being delightful

[167]

let the words appear, and occasionally was so fluent, so inevitable, that it made the words seem even simpler and more conversational than they are. Jerome Kern composed nearly all of the Princess shows and the collected scores are impressive. He is the most erudite of our simple composers and he manipulates material with inordinate skill. He can adapt German folksong (Freut euch das Leben underlies Phoebe Snow); he didn't do so well by Kingdom Comin', which was botched and cut; he also under stands Sullivan. But his best work, The Siren Song, The Little Ships, The Sun Shines Brighter, have a melodious line, a structure, and a general tidiness of execution which are all their own. The Siren Song corresponds exactly to the Viennese waltz, but both the words and the music are impersonal; they are a gentle hymn to seduction, with humour. Scattered between languorous rhythms are bursts of gaiety, like a handful of pebbles thrown against a window which doesn't open-for the song ends in a tender melancholy. It is a real achievement. Compare the lines I have quoted above with " Come, come, I love you only, " from The Chocolate Soldier --phrases you would expect to arrive at the same musical conclusion. The crash of " Oh, Hero Mine! " in the second is good drama, saved from being too obvious by being sung to the coward Sergius and not to the protagonist Bluntschli. But in comparison the gentle ending of The Siren Song is, as song, superior: " So

[168]

sang the Sirens, ages and ages ago" -and you take it or leave it. The music, at least, is not forcing your hand.

The Princess shows never had any great stars; instead, they had the one quality which always makes for success-- esprit de corps. In each the company was aware of the nature and quality of the piece it was playing, and it worked in variations of that genial and sophisticated atmosphere. It was simply against the tone of the Princess shows to be dull; and I, who like nearly all musical shows, found in them my greatest delight.

They passed into something else because they were exquisitely proportioned on a small scale--the scale, by the way of The Beggar's Opera, which they resembled--and the whole tendency of the time was toward elaboration. They involved small choruses, little eccentric dancing, and required no humorist hors de texte. I count it a triumph for Mr. Dilling ham, as well as for the others concerned, that they have been able to preserve so much of the Princess in some of the Globe productions. The best of these, I think, is Good-morning, Dearie. It has an adequate plot; it has room for Harland Dixon, a fine dancer; for Ada Lewis, an expert broad comedienne; for Maurice and his partner, whose name I don't remember; for a large dancing chorus and for stunts; better still it did little to hinder Jerome Kern. It was here that he took the most famous of waltzes

[169]

and implicated it masterfully in a blues; and here that all the seductiveness and gaiety of the Princess music returned with Ka-lu-a and Didn't You Believe? There were a few faults in the production; the dè cor lacked freshness, although it didn't actually off end; the Chinese scene was hackneyed. But on the whole it is the best musical comedy I have seen since the Princess shows.

What forced us to be elaborate was not the memory of the Viennese type, but the growing complexity of revue, always cutting into musical comedy. It should be noted that Around the Map (which I hold the best musical comedy-not operetta-I saw before the Princess shows) first brought Joseph Urban into the field, taking him from the Boston Opera House and pushing him on the way to Ziegfeld, where he was tardily recognized by the Metropolitan for whom he has made Oberon! Around the Map had some twenty scenes, it dealt with a trip around the world in search of safety socks, and was all gay (with Else Alder), all good music (Caryll) and only the beginning of elaboration. But Mr. Berlin's two shows and a host of others indicated that to survive musical comedy would have to appear lavish. Comparatively simple shows still occur-- Tangerine was one; but we seem to be in for something fairly elaborate-in music as in the Le-Baron-Kreisler pieces, in dè cor as in the Shubert-Century productions, in stars and stunts as in Dillingham's.

[170]

I do not pretend to cover the ground, and to name the names, in this sketch; not even to characterize all the types. I don't know what to say about Mary, in which George M. Cohan worked a chorus into a state of frantic energy and Louis Hirsch provided The Love Nest; nor of twenty other individual successes. One composer remains whose work is often so good, whose case is so illuminating, that he must be considered. That is Victor Herbert. It should be said at once that even long after his early successes he composed a fine musical comedy, The Only Girl. The difficulty about Mr. Herbert is that he has succumbed to the American habit of thinking that grand opera is great opera. I have heard him at one of his premiè res speaking from the conductor's dais to assure the audience that the present piece was in the high line of operetta, that more pieces like it would put an end to the vulgarity of musical shows. The regrettable fact was that The Madcap Duchess put an end to nothing but itself; I recall the name, that Ann Swinburne was in it, and that it had a good patter song; the rest was doleful. Whereas two weeks later in the same house I heard The Lady of the Slipper, in which Mr. Herbert, setting out to write an ordinary simple musical show, was a thoroughly competent composer, full of ingenuity and interest and taste and invention. If he had only taken his eyes off the Metropolitan Opera House he would probably have been the best of the lot to-day. He suffers--

[171]

although he is vastly respected--because he failed in respect to the fine art of the musical show. The wonderful thing about that art is that it is made up of varied elements which are fused into something greater than themselves. There is a song and dance by Julia Sanderson, who is not a great artist; or the sudden apparition of a little man pursued in a harem, bounding upon a scarlet pouffe six feet in diameter and nuzzling like a dog--Jimmy Barton, in fact, who is one; and the rambling story told by Percival Knight in The Quaker Girl or the drunken scene by Clifton Crawford in The Peasant Girl; there is In the Night, from The Queen of the Movies or Johnny Dooley falling out of the clerk's desk in Listen, Lester; there is Donald Brian, the perpetual jeune premier, or the amazing Spanish song in Apple Blossoms, or a setting designed by Norman-Bel Geddes or costumes by Helen Dryden or the Sandman song from The Dollar Princess, or the entrance of the Bulgarians in The Chocolate Soldier or the wickedly expert prosody of Brian Hooker. What is it takes all of these and composes them into something beautiful and entertaining? Skill in production is part of it, but not all, for the same elements: colour, light, sound, movement, can be combined into other forms which lack that particular air of urbanity, of well-being, of rich contentment and interest which is the special atmosphere of musical shows. I can only find a word and say that the secret resides in it-high

[172]

spirits. For a musical comedy, even a sentimental one, must be high-spirited in execution--that was the lesson of an unsentimental one, The Beggar's Opera; and at the same time there must be some courage, some defiance of nature and sound sense, a feeling for fantasy, which means that the life of the spirit is high, even when the life of the body is in chains. It is for this freedom of the spirit, released by music as always and diverted by all the other elements in them, that these shows are cherished. It is, naturally, as a counter-attack on solemnity that I am going to found my theatre.

[173]

The One-Man Show

(p. 177 - 188)

WHEN all the other grave aesthetic questions about the stage are answered, some profound theorist may explain the existence of the one-man show. Since I am not a materialist, I cannot concede the obvious solution--that a man finds enough money to produce himself in a Broadway show-because there is something attractive and mysterious about this type of entertainment which the explanation fails to explain.

The theory of the one-man show is apparently that there are individuals so endowed, so versatile, and so beloved, that no other vehicle will suffice to let them do their work. Conversely, that they are of such quality that they suffice for the strange entertainment with which they are surrounded and that nothing else matters provided they are long and frequent on the stage. Six men and two women are in the first roster of the one-man show: Fred Stone, Ed Wynn, Raymond Hitchcock, Eddie Cantor, Frank Tinney, and Al Jolson; below them, leading the women, Elsie Janis and Nora Bayes. And omitting Jolson because he is so great that he cannot be put in any company, the greatest one-man show was one in which none of these appeared--it was one in which even the man himself didn't appear. It was a show in which one man succeeded where all of these, this time not excluding Jolson, had failed: for he made the whole production his kind of show--and the others have never quite managed to do more than make themselves.

[177]

The chief example of this failure is Hitchcock, whose series lapses ever so often, leaving him stranded on the bleak shore of a Pin Wheel Revue --an artistic, an intellectual, an incredibly stupid production which Hitchy manfully tried first to save and then to abandon. There were in the better Hitchy shows other first-rate people: one who masqueraded as Joseph Cook and was none other than Joe Cook the Humorist out of vaudeville and out of his element; Ray Dooley was with Hitchy, I believe, and there were always good dancers. Hitchy kept on the stage a long time, as conferencier and as participant, and his amiable drollery was always at the same level--just enough. He never quite concealed the strain of making a production go; one always wanted to be much more amused, and Hitchy never got beyond the episode of the Captain of the Fire Brigade or trying to buy the middle two-cent stamp in a sheet of a hundred. A series of vaudeville sketches doesn't make a one-man show, even if he plays in all of them; and the moment Hitchcock was off, Hitchy-koo went to pieces, some good and some bad, and all trying a little too hard to be something else.

Eddie Cantor and Al Jolson appear in the two different Winter Garden types of show--the Jolson and the Winter Garden in impuris naturalibus. Jolson infuses something both gay and broad into his pieces; even the recurrence of Lawrence D'Orsay can not win back the original Winter Garden atmosphere

[178]

and even the disappearance of Kitty Doner cannot diminish Jolson's private quality. Of the straight Winter Garden shows, the 1922 with Eddie Cantor was the best in ten years, made so by Cantor and made by him, in spite of the billing, into a one-man show. The nervous energy of Cantor isn't sufficient to animate the active, but indifferent choruses of the Shuberts. One thing, however, he can do superbly--the lamb led to the slaughter. It is best when he chooses to play the timid, Ghetto-bred, pale-faced Jewish lad, seduced by glory or the prospects of pay into competing with athletes and bruisers. One thing he cannot do and should learn not to try--the blackface song and comedy of his master, Jolson. The scenes of violence vary; that of the osteopath was an exploitation of meaningless brutality; I cared for nothing after Eddie's frightened entrance, " Are you the Ostermoor? " But the aviation examination and the application for the police force were excellent pieces of construction, holding sympathy all the way through and keeping on the safe side of nausea. Both of these were before the Winter Garden days and the Winter Garden exploit was better than either. He played here a cutter in a hand-me-down clothing store and it was his function to leap into the breach whenever a customer showed the slightest tendency

[179]

to leave without buying a suit. The victim was obsessed by some idea of having " a belt in the back" and was forced into sailor suits and fancy costume and was generally made miserable. Eddie's terrific rushes from the wings, his appeals to God to strike him dead " on the spot" if the suit now being tried on wasn't the best suit in the world, his helplessness and his, " Well, kill me, so kill me, as apology when his partner revealed the damning fact that that happened to be the man's old suit-all of this was worth the whole of the Potash-Perlmutter cycle. And the whole-heartedness of Cantor's violence-essentially the bullying of a coward who has at last discovered some one weaker than himself, was faultless. He sings well the slightly suggestive songs like After the Ball (new version), and his three broken dance steps with the sawing motion of his gloved hands create an image exceedingly precise and palpable. There is in him just enough for the one-man show, but so far it has been limited by his tendency to imitate and by failure to develop his own sources of strength. Even in Kid Boots he just fails to make the grade.

The one-man show requires its leader to leave nothing in himself unexploited--there is too much for him to do and he must take everything on himself the requirements are exactly opposite to those of the vaudeville act where the actor must work in the briefest compass, with the utmost concentration, and get his effects in the shortest time. Frank Tinney's suc-

[ 180]

cess in vaudeville marks the limitations of his success in his shows--for he imposed on vaudeville that languid easy-going manner of his and was just enough out of vaudeville tempo (he is very deceptive in this) to appear to be a novelty there. In essence he isn't a good one-man, for his line is limited and his humour and his good humour (in which he is matched only by Ed Wynn) are not capable of the strain of a long winter's evening entertainment. Tinney was excellent in a quarrel scene with Bernard Granville (in a Ziegfeld Follies, I think) the two pacing in opposite directions, the width of the stage between them, always from footlights to backdrop and never crossing the stage; he was disputatious and entertaining on the negative of the proposition that the Erie railroad (pronounced for reasons of his own, Ee-righ) is a very expensive railroad; his appearance in Watch Your Step was almost perfect. (Consult Mr A. Woollcott's Shouts and Murmurs for everything about Tinney; Mr Woollcott's descriptions are accurate and evocative and he errs only in his estimate of Tinney's quality.) Tinney has everything except the

[18l]

excess of vitality, the surcharge of genius. He has method nearly to perfection and it is a wholly original, ingratiating, and, up to a certain point, adaptable method. What he has done is to destroy the " good joke, " for all of Tinney's jokes are bad ones and he gets his effect by fumbling about with them, by lengthening the preliminaries, by false starts, erasures, corrections--until his arrival at the point relieves the suspense. I have heard him take at least ten minutes to put over: " Lend me a dollar for a week, old man.-Who is the weak old man? " and not a moment was superfluous. He is expert at kidding the audience, and as he is never in character he never steps out. 'There isn't quite enough of him, that is all.

There is enough of Fred Stone for versatility and not enough for specific personal appeal. As acrobat, dancer, ventriloquist, and cut-up Stone is easily in the lead; but the unnamable quality is lacking. See him climbing up an arbour to meet his Juliet in the balcony; he is discovered, hangs head downward in peril of his life, seizes a potted flower and with it begins to dust the vines--it is Chaplinesque in conception and beautifully executed. See him on the slack rope continually on the point of falling off and continually recovering and seeming to hang on by his boot toe; or in The Lady of the Slipper making a beautiful series of leaps from chair to divan, from divan to table, to a triumphant exit through the

[182]

unsuspected scenery; or in another quality recall the famous " Very good, Eddie, " of Chin-Chin. He is incredible; one wouldn't miss him for worlds; yet it is always what he does and not himself that constitutes the attraction. I wonder whether I do not wrong him altogether by classing him with the one-men, for it was always some thing more than Montgomery and Stone in the days of The Red Mill and Stone does not exaggerate himself on the stage. His command of attributes is greater than that of any other player; he does everything with a beautiful, error-less accuracy--and the pleasure of seeing things exactly right, all the time, is not to be underestimated. It is Ed Wynn's pleasure to make everything seem utterly haphazard. Wynn is absurd in the theatre--there is always something left unresolved in reducing him to the lowest term, and he is incommensurable because there are no standards for him and no similars. I prefer to see him wandering through a good revue, changing hats, worrying about a " rewolwer" in the first scene and stopping dead in the twentieth to declare that it wasn't a " rewolwer" at all, but a pis-

[183]

tol. When he came to put on a one-man show he preserved the best part of this incoherence. He made it his business to appear before a drop curtain and explain in an amazing vocabulary and with pains taking gravity exactly what was to occur in the next scene. He affects to be awkward (to quote him, I might go so far as to call him uncouth.... I think I will call him uncouth.... He is uncouth); his gestures are florid and wide, his earnestness makes all things vivid. Each of these explanations involves a bad pun and none, of course, has anything to do with the scene that actually follows. Like Jolson and Cantor, he takes the stage at a given moment and entertains. His famous inventions seemed to be the crudest form of humour--a typewriter carriage for eating corn on the cob, a burning candle to set in one's ears in order to wake up in time--yet sheer ebullition carried them high into the field of " nice, clean fun." Wynn's words come tumbling out of him, agglutinated, chaotic, disorderly; he is abashed by his own occasional temerity, he is timid and covers it with brashness-and all of this is a carefully created personage; it is not Ed Wynn. He has found a little odd corner of life which no one else cultivates; it is a sort of rusticity in the face of simple things; he is a perpetual immigrant obsessed by hats and shoes and words and small ideas, instead of bothering about skyscrapers. The deepness of his zanylike appreciation of every-day things is the secret of his

[ 184]

capacity for making them startling and funny. His one fault is the show with which he surrounds him self.

I have never seen Elsie Janis better than she was in The Lady of the Slipper --with the exception of Gaby Deslys I have never seen any woman comparable to Miss Janis in that piece, and in it she had qualities which ought to have made her appearance in an individual show a much greater success than it actually turned out to be. For, except a voice, Miss Janis has everything. She is a beautiful dancer and her legs are handsomer than Mistinguett's, and she is the finest mimic I have ever seen on the stage, several shades ahead of Ina Claire. An exceptional intelligence operates in the creation of these caricatures, for they are all created by seizing upon vital characteristics of tone, gesture, tempo of movement, spirit; and the arrangement of her hair and the contortions of her face are only guide-signs to the accomplished act. She is herself of an abounding grace, a suppleness of body and of mind, and the measure of her skill is the exact degree in which her grace and simplicity are transformed into harshness or angularity or sophistication as she passes one after another of our stage personalities before her mirror. This year I saw her in a Paris music-hall take off Mistinguett and Max Dearly. She presented them singing Give Me Moonlight in their own imagined versions and her throaty " Give me a gas light" for the creator of

[185]

Mon Homme was superb. She offered to sing it, at the end, as she herself ought to sing it--and danced it without uttering a sound. It reminded one of Irene Castle in Watch Your Step. For an exact calculation of her capacities and a sensible, modest intention to stay within them and to exploit them to the limit are parts of Elsie Janis's intelligence. To be sure, it isn't her intelligence--it is her loveliness and her talent that endear her to us. But it is grateful, for once in a way, to find a talent so great, a loveliness so irresistible, joined to an intelligence which sets all in motion and spoils nothing.

I suspect that in spite of the best of the one-man shows there is something wrong with the idea--perhaps because the environment requires more than any man has yet been able to give. And the one perfect example is, as I have suggested, proof of this. Because Stop! Look! Listen! which was only a moderate success on Broadway and involved the talents of Gaby Deslys, Doyle and Dixon, Harry Fox, Tempest and Sunshine, the beautiful Justine Johnston, Helen Barnes, Helen Dryden as costumer and Robert McQuinn as scenic designer, a beautiful chorus and an excellent producer, was actually the one-man show of Irving Berlin. For once a complete and varied show expressed the spirit of one man to perfection. In that piece, Berlin wrote two of his masterpieces and about four other superb songs; and, more than that, suffused the entire production with the gay spirit

[186]

of his music. There occurred The Ragtime Melodrama danced by Doyle and Dixon--only the Common Clay scene from the Cohan revue ever approached it, and Doyle and Dixon never danced better (unless, possibly, a quarter of an hour earlier in The Hula Hula); there was The Girl on the Magazine Cover, perfectly set and costumed, a really good sentimental song with its quaint introduction of Lohengrin (not the Wedding March); there was When I Get Back to the U. S. A. sung against a chorus of My Country, 'Tis of Thee; there was Gaby's wicked Take Off a Little Bit and Harry Fox's Press-Agent Song --and finally the second of Berlin's three great tributes to his art: I Love a Piano, which, like the mother of Louis Napoleon, he wrote for six pianos and in which everything in syncopation up to that time was epitomized and carried to a perfect conclusion. What ever was gay, light, colourful, whatever was accurate, assured, confident, and good-humoured, was in this miraculous production. I saw it twelve times in two weeks--lured partly, I must confess, by the hope that Harry Pilcer would break at least a leg in his fall down the golden stairs. He never did; in spite of which, seeing it again, months later, it still seemed to me the apotheosis of pure show. I think I could reconstruct every moment of it, including the useless plot and Justine Johnston's ankles; it seems a pity that all of it, the ephemeral and the permanent, should have already passed from the stage. It was a

[187]

beginning in ragtime operetta which Mr Berlin has never followed up; his inexhaustible talents have been diverted into other things; he is now a maker of revues. Yet when he saw The Beggar's Opera, Mr Berlin felt something plucking at his sleeve, reminding him that it was his job, and his alone, to create the comparable type for America. At that moment he thought back to Stop! Look! Listen! --but he had already begun to build the Music Box--and we must wait patiently for what time will bring as a real successor to his one-man show. At any rate, we have had it. We know; now, what it can amount to--and it is enough. Enough, at any rate, to put the veritable one-man show fairly definitely out of the running.

[188]

The Daemonic in the American Theatre

(pages 191-200)

ONE man on the American stage, and one woman, are possessed--Al Jolson and Fanny Brice. Their daemons are not of the same order, but together they represent all we have of the Great God Pan, and we ought to be grateful for it. For in addition to being more or less a Christian country, America is a Protestant community and a business organization-and none of these units is peculiarly prolific in the creation of daemonic individuals. We can bring forth Roosevelts--dynamic creatures, to be sure; but the fury and the exultation of Jolson is a hundred times higher in voltage than that of Roosevelt; we can produce courageous and adventurous women who shoot lions or manage construction gangs and remain pale beside the extraordinary " cutting loose" of Fanny Brice.

To say that each of these two is possessed by a daemon is a mediaeval and perfectly sound way of expressing their intensity of action. It does not prove anything-not even that they are geniuses of a fairly high rank, which in my opinion they are. I use the word possessed because it connotes a quality lacking elsewhere on the stage, and to be found only at moments in other aspects of American life-in religious mania, in good jazz bands, in a rare outbreak of mob violence. The particular intensity I mean is exactly what you do not see at a baseball game, but may at a prize fight, nor in the productions of David Belasco,

[191]

nor at a political convention; you may see it on the Stock Exchange and you can see it, canalized and disciplined, but still intense, in our skyscraper architecture. It was visible at moments in the old Russian Ballet.

In Jolson there is always one thing you can be sure of: that whatever he does he does at the highest possible pressure. I do not mean that one gets the sense of his effort, for his work is at times the easiest seeming, the most effortless in the world. Only he never saves up-for the next scene, or the next week, or the next show. His generosity is extravagant; he flings into a comic song or three-minute impersonation so much- energy, violence, so much of the totality of one human being, that you feel it would suffice for a hundred others. In the days when the runway was planked down the centre of every good theatre in America, this galvanic little figure, leaping and shouting--yet always essentially dancing and singing--upon it was the concentration of our national health and gaiety. In Row, Row, Row he would bounce up on the runway, propel himself by imaginary oars over the heads of the audience, draw equally imaginary slivers from the seat of his trousers, and infuse into the song something wild and roaring and insanely funny. The very phonograph record of his famous Toreador song is full of vitality. Even in later days when the programme announces simply " Al Jolson" (about 10.15 P.M. in each of his reviews)

[192]

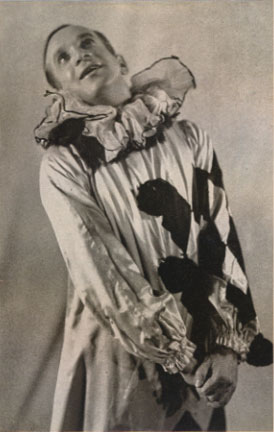

Fanny Brice

he appears and sings and talks to the audience and dances off-and when he has done more than any other ten men, he returns and, blandly announcing that " You ain't heard nothing yet, " proceeds to do twice as much again. He is the great master of the one-man show because he gives so much while he is on that the audience remains content while he is off-and his electrical energy almost always develops activity in those about him.

If it were necessary, a plea could be made for violence per se in the American theatre, because everything tends to prettify and restrain, and the energy of the theatre is dying out. But Jolson, who lacks discipline almost entirely, has other qualities besides violence. He has an excellent baritone voice, a good ear for dialect, a nimble presence, and a distinct sense of character. Of course it would be impossible not to recognize him the moment he appears on the stage; of course he is always Jolson-but he is also always Gus and always Inbad the Porter, and always Bombo. He has created a way of being for the characters he takes on; they live specifically in the mad world of the Jolson show; their wit and their bathos are singularly creditable characteristics of themselves-not of Jolson. You may recall a scene I think the show was called Dancing Around - in which a lady knocks at the door of a house. From within comes the voice of Jolson singing, " You made me love you, I didn't wanna do it, I didn't wanna do

[193]

it" --the voice approaches, dwindles away, resumes -- it is a swift characterization of the lazy servant coming to open the door and ready to insult callers, since the master is out. Suddenly the black face leaps through the doorway and cries out, " We don' want no ice, " and is gone. Or Jolson as the black slave of Columbus, reproached by his master for a long absence. His lips begin to quiver, his chin to tremble; the tears are approaching, when his human independence softly asserts itself and he wails, " We all have our moments. " It is quite true, for Jolson's technique is the exploitation of these moments; he has himself said that he is the greatest master of hokum in the business, and in the theatre the art of hokum is to make each second count for itself, to save any moment from dulness by the happy intervention of a slap on the back, or by jumping out of character and back again, or any other trick. For there is no question of legitimacy here-everything is right if it makes 'em laugh.

He does more than make 'em laugh; he gives them what I am convinced is a genuine emotional effect ranging from the thrill to the shock. I remember coming home after eighteen months in Europe, during the war, and stepping from the boat to one of the first nights of Sinbad. The spectacle of Jolson's vitality had the same quality as the impression I got from the New York sky line-one had forgotten that there still existed in the world a force so boundless,

[194]

an exaltation so high, and that anyone could still storm Heaven with laughter and cheers. He sang on that occasion 'N Everything and Swanee. I have suggested elsewhere that hearing him sing Swanee is what book reviewers and young girls loosely call an experience. I know what Jolson does with false sentiment; here he was dealing with something which by the grace of George Gershwin came true, and there was no necessity for putting anything over. In the absurd black-face which is so little negroid that it goes well with diversions in Yiddish accents, Jolson created image after image of longing, and his existence through the song was wholly in its rhythm.

Five years later I heard Jolson in a second-rate show, before an audience listless or hostile, sing this out dated and forgotten song, and create again, for each of us seated before him, the same image-and saw also the tremendous leap in vitality and happiness which took possession of the audience as he sang it. It was marvelous. In the first weeks of Sinbad he sang the words of 'N Everything as they are printed. Gradually (I saw the show in many phases) he interpolated, improvised, always with his absolute sense of rhythmic effect; until at the end it was a series of amorous cries and shouts of triumph to Eros. I have heard him sing also the absurd song about " It isn't raining rain, It's raining violets" and remarked him modulating that from sentimentality into a conscious bathos, with his gloved fingers flittering together and

[195]

his voice rising to absurd fortissimi and the general air of kidding the piece.

He does not generally kid his Mammy songs-as why should he who sings them better than anyone else? He cannot underplay anything, he lacks restraint, and he leans on the second-rate sentiment of these songs until they are forced to render up the little that is real in them. I dislike them and dislike his doing them-as I dislike Belle Baker singing Elie, Elie! But it is quite possible that my discomfort at these exhibitions is proof of their quality. They and a few very cheap jokes and a few sly remarks about sexual perversions are Jolson's only faults. They are few. For a man who has, year after year, established an intimate relation with no less than a million people, every twelvemonth, he is singularly uncorrupted. That relation is the thing which sets him so far above all the other one-manshow stars. Eddie Cantor gives at times the effect of being as energetic; Wynn is always and Tinney sometimes funnier. But no one else, except Miss Brice, so holds an audience in the hollow of the hand. The hand is steady; the audience never moves. And on the great nights when everything is right, Jolson is driven by a power beyond himself. One sees that he knows what he is doing, but one sees that he doesn't half realize the power and intensity with which he is doing it. In those moments I cannot help thinking of him as a genius.

[196]

Quite to that point Fanny Brice hasn't reached. She hasn't, to begin with, the physical vitality of Jolson. But she has a more delicate mind and a richer humour--qualities which generally destroy vitality altogether, and which only enrich hers. She is first a great farceur; and in her songs she is exactly in the tradition of Yvette Guilbert, without the range, so far as we know, which enabled Mme Guilbert to create the whole of mediaeval France for us in ten lines of a song. The quality, however, is the same, and Fanny's evocations are as vivid and as poignant as Yvette's-they require from us exactly the same tribute of admiration. She has grown in power since she sang and made immortal, I Should Worry. Hear her now creating the tragedy of SecondHand Rose or of the one Florodora baby who-- " five little dumbells got married for money, And I got married for love...." These things are done with two-thirds of Yvette Guilbert's material missing, for there are no accessories and, although the words (some of the best are by Blanche Merrill) are good, the music isn't always distinguished. And the effects are irreproachable. Give Fanny a song she can get her teeth into, Mon Homme, and the result is less certain, but not less interesting. This was one of a series of realistic songs for Mistinguett, who sang it very much as Yvonne George did when she appeared in America. Miss Brice took it lento affetuoso; since the precise character of the song had changed a bit

[197]

from its rather more outspoken French original. Miss Brice suppressed Fanny altogether in this song-she was being, I fear, " a serious artist"; but she is of such an extraordinary talent that she can do even this. Yvonne. George sang it better simply because the figure she evoked as Mon Homme was exactly the fake apache about whom it was written, and not the " my feller" who lurked behind Miss Brice. It was amusing to learn that without a Yiddish accent and without those immense rushes of drollery, without the enormous gawkishness of her other impersonations, Miss Brice could put a song over. But I am for Fanny against Miss Brice and to Fanny I return.

Fanny is one of the few people who " Make fun." She creates that peculiar quality of entertainment which is wholly light-hearted and everything else is added unto her. Of this special quality nothing can be said; one either sees it or doesn't, savours it or not. Fanny arrives on the scene with an indescribable gesture--after seeing it twenty times I believe that it consists of a feminine salute, touching the forehead and then flinging out her arm to the topmost gallery. There is magic in it, establishing her character at once -the magic must reside in her incredible elbow. She hasn't so much to give as Jolson, but she gives it with the same generosity, there are no reserves, and it is all for fun. Her Yiddish Squow (how else can I spell that amazing effect?) and her Heiland Lassie are examples-there isn't an arriere-pensee in them.

[198]

Al Jolsen

" The Chiff is after me... he says I appil to him... he likes my type - - " It is the complete give away of herself and she doesn't care.

And this carelessness goes through her other exceptional qualities of caricature and satire. For the first there is the famous Vamp, in which she plays the crucial scene of all the vampire stories, preluding it with the first four lines of the poem Mr Kipling failed to throw into the wastepaper basket, and fatuously adding, " I can't get over it" --after which point everything is flung into another plane-the hollow laughter, the haughty gesture, the pretended compassion, that famous defense of the vampire which here, however, ends with the magnificent line, " I may be a bad woman, but I'm awful good company." In this brief episode she does three things at once: recites a parody, imitates the moving-picture vamp, and creates through these another, truly comic character. For satire it is Fanny's special quality that with the utmost economy of means she always creates the original in the very process of destroying it, as in two numbers which are exquisite, her present opening song in vaudeville with its reiterations of Victor Hebert's Kiss Me Again, and her Spring Dance. The first is pressed far into burlesque, but before she gets there it has fatally destroyed the whole tedious business of polite and sentimental concert-room vocalism; and the second (Fanny in ballet, with her amazingly angular parody of five-position dancing) puts an end

[199]

forever to that great obsession of ours, classical interpretative dancing.

Fanny's refinement of technique is far beyond Jolson's; her effects are broad enough, but her methods are all delicate. The frenzy which takes hold of her is as real as his. With him she has the supreme pleasure of knowing that she can do no wrong-and her spirits mount and intensify with every moment on the stage. She creates rapidly and her characterizations have an exceptional roundness and fulness; when the daemon attends she is superb.

It is noteworthy that these two stars bring something to America which America lacks