Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

The Vulgar Comic Strip

|

|

(pages 213-228)

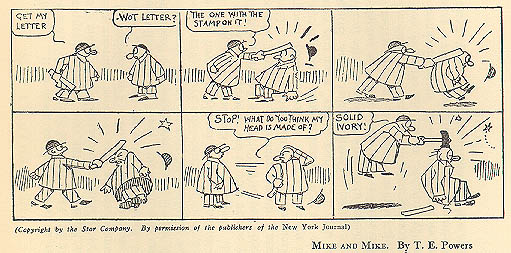

OF all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dulness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

Certainly there is a great deal of monotonous stupidity in the comic strip, a cheap jocosity, a life-of-the-party humour which is extraordinarily dreary. There is also a quantity of bad drawing and the intellectual level, if that matters, is sometimes not high. Yet we are not actually a dull people; we take our fun where we find it, and we have an exceptional capacity for liking the things which show us off in ridiculous postures--a counterpart to our inveterate passion for seeing ourselves in stained-glass attitudes. And the fact that we do care for the comic strip that Jiggs and Mutt-and-Jeff and Skinnay and the Gumps have entered into our existence as definitely as Roosevelt and more deeply than Pickwick-ought to make them worth looking at, for once. Certainly they would have been more sharply regarded if they had produced the counterpart of Chaplin in the comic film--a universal genius capable of holding the multitude

[213]

and exciting the speculations of the intellectuals. It happens that the actual genius of the comic strip, George Herriman, is of such a special sort that even when he is recognized he is considered something apart and his appearance among other strips is held to be only an accident.

It is by no means an accident, for the comic strip is an exceptionally supple medium, giving play to a variety of talents, to the use of many methods, and it adapts itself to almost any theme. The enormous circulation it achieves imposes certain limitations: it cannot be too local, since it is syndicated throughout the country; it must avoid political and social questions because the same strip appears in papers of divergent editorial opinions; there is no room in it for acute racial caricature, although no group is immune from its mockery. These and other restrictions have gradually made of the comic strip a changing picture of the average American life-and by compensation it provides us with the freest American fantasy.

In a book which appeared about two years ago, Civilization in the United States, thirty Americans rendered account of our present state. One of them, and one only, mentioned the comic strip--Mr Harold E. Stearns--and he summed up the " intellectual" attitude perfectly by saying that Bringing Up Father will repay the social historian for all the attention he gives it. I do not know in what satisfactions the social historian can be repaid. I fear that the actual

[214]

fun in the comic strip is not one of them. Bringing Up Father, says Mr Stearns, " symbolizes better than most of us appreciate the normal relation of American men and women to cultural and intellectual values. Its very grotesqueness and vulgarity are revealing " (italics mine). (Query: Is it vulgar of Jiggs to prefer Dinty's cafe to a Swami's lecture 1 Or of Mrs Jiggs to insist on the lecture! Or of both of them to be rather free in the matter of using vases as projectiles? What, in short, is vulgar?) I am far from quarreling with Mr Stearns' leading idea, for I am sure that a history of manners in the United States could be composed with the comic strip as its golden thread; but I think that something more than its vulgarity would be revealing.

The daily comic strip arrived in the early nine ties-perhaps it was our contribution to that artistic age-and has gone through several phases. In 1892 or thereabouts Jimmy Swinnerton created Little Bears and Tigers for the San Francisco Examiner; that forerunner has passed away, but Swinnerton remains, and everything he does is observed with respect by the other comic-strip artists; he has had more influence on the strip even than Wilhelm Busch, the German whose Max und Moritz were undoubt edly the originals of the Katzenjammer Kids. The strip worked its way east, prospered by William Randolph Hearst especially in the coloured Sunday Supplement, and as a daily feature by the Chicago

[215]

Daily News, which was, I am informed, the first to syndicate its strips and so enabled Americans to think nationally. About fifteen years ago, also in San Francisco, appeared the first work of Bud Fisher, Mr Mutt, soon to develop into Mutt and Jeff, the first of the great hits and still one of the best known of the comic strips. Fisher's arrival on the scene corresponds to that of Irving Berlin in ragtime. He had a great talent, hit upon something which took the popular fancy, and by his energy helped to establish the comic strip as a fairly permanent idea in the American newspaper.

The files of the San Francisco Chronicle will one day be searched by an enthusiast for the precise date on which Little Jeff appeared in the picture. It is generally believed that the two characters came on together, but this is not so. In the beginning Mr Mutt made his way alone; he was a race-track follower who daily went out to battle and daily fell. Clare Briggs had used the same idea in his Piker Clerk for the Chicago Tribune. The historic meeting with Little Jeff, a sacred moment in our cultural development, occurred during the days before one of Jim Jeffries' fights. It was as Mr Mutt passed the asylum walls that a strange creature confided to the air the notable remark that he himself was Jeffries. Mutt rescued the little gentleman and named him Jeff. In gratitude Jeff daily submits to indignities which might otherwise seem intolerable.

[216]

The development in the last twenty years has been rapid, and about two dozen good comics now exist. Historically it remains to be noted that between 1910 and 1916 nearly all the good comics were made into bad burlesque shows; in 1922 the best of them was made into a ballet with scenario and music by John Alden Carpenter, choreography by Adolph Bolm; costumes and settings after designs by George Herriman. Most of the comics have also appeared in the movies; the two things have much in common and some day a thesis for the doctorate in letters will be written to establish the relationship. The writer of that thesis will explain, I hope, why " movies" is a good word and " funnies, " as offensive little children name the comic pages, is what charming essayists call an atrocious vocable.

Setting apart the strip which has fantasy-it is practised by Frueh and by Herriman--the most interesting form is that which deals satirically with every-day life; the least entertaining is the one which takes over the sentimental magazine love-story and carries it through endless episodes. The degree of interest points to one of the virtues of the comic strip: it is a great corrective to magazine-cover prettiness. Only one or two frankly pretty-girl strips exist. Petey is the only one which owes its popularity to the high, handsome face and the lovely flanks of its heroine, and even there the pompous awkwardness of the persistent lover has a touch of wilful absurdity.

[217]

Mrs Trubble, a second-rate strip unworthy of its originator, is simply a series of pictures dramatizing the vampire home-breaker; I am not even sure she is intended to be pretty. When nearly everything else in the same newspapers is given over to sentimental ity and affected girl-worship, to advice to the love lorn and pretty-prettiness, it is notable that the comic strip remains grotesque and harsh and careless. It is largely concerned with the affairs of men and children, and, as far as I know, there has never been an effective strip made by, for, or of a woman. The strip has been from the start a satirist of manners; remembering that it arrived at the same time as the Chicago World's Fair, recalling the clothes, table manners, and conversation of those days, it is easy to see how the murmured satiric commentary of the strip undermined our self-sufficiency, pricked our conceit, and corrected our gaucherie. To-day the world of Tad, peopled with cake-eaters and finale-hoppers, the world of the Gumps and Gasoline Alley, of Abie the Agent and Mr and Mrs serve the same purpose. I am convinced that none of our realists in fiction come so close to the facts of the average man, none of our satirists are so gentle and so effective. Of course they are all more serious and more conscious of their mission; but-well, exactly who cares?

The best of the realists is Clare Briggs, who is an elusive creator, one who seems at times to feel the medium of the strip not exactly suited to him, and

[218]