Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

On-line simulation of the Maulitania Peace Negotiatons.

|

|

Last names beginning with the letters A through H will be in Group A; letters I through Z will be in Group B.

General Cederick and his staff are to be role-played by members of Group A.

Based on the simulated facts and article below, members of Group A are invited to submit a short position paper for General Cederick, setting forth a proposed opening and fall-back position for the General in the peace negotiations, and responding to the argument that trading justice for peace in these circumstances would violate international law.

Madame Erickson and her staff are to be role-played by members of Group B.

Based on the simulated facts and article below, members of Group B are invited to submit a short position paper for Vice President Erickson, setting forth a proposed opening and fall-back position for the Vice President in the peace negotiations, and making the argument that trading justice for peace in these circumstances would violate international law.

In order to complete the optional on-line simulations for this course, students must go to the Navigation Bar on the left panel. Under the Exercises section, you will find a button for “on-line simulations.” The simulations for each session are available under this button. Written work can be submitted directly or through file upload. Students who post five or more on-line submissions of over 200 words in length during the course (simulations and discussions) will be awarded a Statement of Accomplishment withDistinction for the course.

In order to complete the optional on-line simulations for this course, students must go to the Navigation Bar on the left panel. Under the Exercises section, you will find a button for “on-line simulations.” The simulations for each session are available under this button. Written work can be submitted directly or through file upload. Students who post five or more on-line submissions of over 200 words in length during the course (simulations and discussions) will be awarded a Statement of Accomplishment withDistinction for the course.

From the eXile Files: An Essay on Trading Justice for Peace

By Michael P. Scharf

63 Washington and Lee Law Review 339-376 (2006) [Footnotes deleted for MOOC version]

I. Introduction

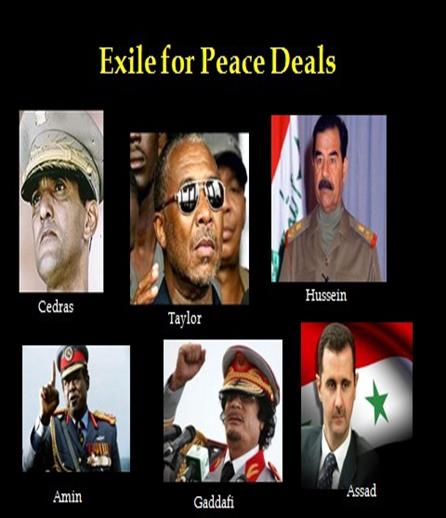

Since 1990, three different U.S. Presidents have accused Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein of committing grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and acts of genocide. Although the Geneva Conventions and the Genocide Convention require state parties to bring offenders to justice, on the eve of the 2003 invasion of Iraq, President George W. Bush offered to call off the attack if Saddam Hussein and his top lieutenants would agree to relinquish power and go into exile. This was no publicity stunt, as some have characterized it. Working through President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt, the United States actively pursued the matter with several Mideast countries, ultimately persuading Bahrain to agree to provide sanctuary to Hussein if he accepted the deal. When Hussein rejected the proposal, Bush promised that the Iraqi leader would be forced from power and prosecuted as a war criminal.

Admittedly, thousands of lives could have been spared if Hussein had accepted the deal. But at the risk of being accused of blindly embracing Kant’s prescription that " justice must be done even should the heavens fall, " this Article argues that it was inappropriate for the Bush Administration even to make the offer, and that if implemented the exile-for-peace deal would have seriously undermined the Geneva Conventions and the Genocide Convention, which require prosecution of alleged offenders without exception.

A few months after the invasion of Iraq, U.S. officials helped broker a deal whereby Liberian President Charles Taylor, who had been indicted for crimes against humanity by the Special Court for Sierra Leone, agreed to give up power and was allowed to flee to Nigeria, where he received asylum. At the time, forces opposed to Taylor, which had taken over most of the country, were on the verge of attacking the capital city Monrovia, and tens of thousands of civilian casualties were forecast. The exile deal averted the crisis and set the stage for insertion of a U.N. peacekeeping mission that stabilized the country and set it on a path to peace and democracy. In contrast to the Hussein case, the Taylor arrangement did not in any way violate international law. This Article explains why international law should treat the two situations differently, prohibiting exile and asylum for Saddam Hussein while permitting such a justice- for-peace exchange in the case of Charles Taylor.

This is the first scholarly article in recent years to focus on the significant issue of exile. Scholarship on the analogous issue of amnesty has been written largely from the point of view of aggressive advocates of international justice, whose writing is based on the assumption that the widespread state practice favoring amnesties constitutes a violation of, rather than a reflection

of, international law in this area. Before analyzing the relevant legal principles, the Article begins with an examination of the practical considerations that counsel for and against the practice of " trading justice for peace." Next, using the Saddam Hussein and Charles Taylor cases as a focal point, the Article analyzes the relevant international instruments which require prosecution under limited circumstances. This is followed by a critique of the popular view that customary international law and the principle of jus cogens broadly prohibit actions that prevent prosecution of crimes under international law. The Article establishes that there does not yet exist a customary international law rule requiring prosecution of war crimes in internal armed conflict or crimes against humanity, but that there is a duty to prosecute in the case of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, the crime of genocide, and torture. Where the duty to prosecute does apply, it is important that states and international organizations honor it, lest they signal disrespect for the important treaties from which the duty arises, potentially putting their own citizens at risk and generally undermining the rule of law.

II. Practical Considerations

A. Interests Favoring Exile, Asylum, and Amnesty

Notwithstanding the popular catch phrase of the 1990s—" no peace without justice" — achieving peace and obtaining justice are sometimes incompatible goals—at least in the short term. In order to end an international or internal conflict, negotiations often must be held with the very leaders who are responsible for war crimes and crimes against humanity. When this is the case, insisting on criminal prosecutions can prolong the conflict, resulting in more deaths, destruction, and human suffering.

Reflecting this reality, during the past thirty years, Angola, Argentina, Brazil, Cambodia, Chile, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Ivory Coast, Nicaragua, Peru, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Togo, and Uruguay have each, as part of a peace arrangement, granted amnesty to members of the former regime that committed international crimes within their respective borders. With respect to five of these countries—Cambodia, El Salvador, Haiti, Sierra Leone, and South Africa—" the United Nations itself pushed for, helped negotiate, or endorsed the granting of amnesty as a means of restoring peace and democratic government."

In addition to amnesty (which immunizes the perpetrator from domestic prosecution), exile and asylum in a foreign country (which puts the perpetrator out of the jurisdictional reach of domestic prosecution) is often used to induce regime change, with the blessing and involvement of significant states and the United Nations. Peace negotiators call this the " Napoleonic Option, " in reference to the treatment of French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte who, after his defeat at Waterloo in 1815, was exiled to St. Helena rather than face trial or execution. More recently, a number of dictators have been granted sanctuary abroad in return for relinquishing power. Thus, for example, Ferdinand Marcos fled the Philippines for Hawaii; Baby Doc Duvalier fled Haiti for France; Mengisthu Haile Miriam fled Ethiopia for Zimbabwe; Idi Amin fled Uganda for Saudi Arabia; General Raoul Cedras fled Haiti for Panama; and Charles Taylor fled Liberia for exile in Nigeria—a deal negotiated by the United States and U.N. envoy Jacques Klein.

As Payam Akhavan, then Legal Adviser to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, observed a decade ago: " [I]t is not

unusual in the political stage to see the metamorphosis of yesterday’s war monger into today’s peace broker." This is because, unless the international community is willing to use force to topple a rogue regime, cooperation of the leaders is needed to bring about peaceful regime change and put an end to violations of international humanitarian law. Yet, it is not realistic to expect them to agree to a peace settlement if, directly following the agreement, they would find themselves or their close associates facing potential life imprisonment.

This conclusion finds support in the observations of the 2004 Report of the International Truth and Reconciliation Commission for Sierra Leone:

The Commission is unable to condemn the resort to amnesty by those who negotiated the Lomé Peace Agreement [which provides amnesty to persons who committed crimes against humanity in Sierra Leone]. The explanations given by the Government negotiators, including in their testimonies before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, are compelling in this respect. In all good faith, they believed that the RUF [insurgents] would not agree to end hostilities if the Agreement were not accompanied by a form of pardon or amnesty..... The Commission is unable to declare that it considers amnesty too high a price to pay for the delivery of peace to Sierra Leone, under the circumstances that prevailed in July 1999. It is true that the Lomé Agreement did not immediately return the country to peacetime. Yet it provided the framework for a process that pacified the combatants and, five years later, has returned Sierra Leoneans to a context in which they need not fear daily violence and atrocity.

In brokering the Charles Taylor exile deal, the United States and United Nations were particularly encouraged by the success of similar amnesty/exile for peace arrangements relating to Haiti and South Africa in the 1990s. From 1990–1994, Haiti was ruled by a military regime headed by General Raol Cedras and Brigadier General Philippe Biamby, which executed over 3000 civilian political opponents and tortured scores of others. The United Nations mediated negotiations at Governors Island in New York Harbor, in which the military leaders agreed to relinquish power and permit the return of the democratically elected President (Jean-Bertrand Aristide) in return for a full amnesty for the members of the regime and a lifting of the economic sanctions imposed by the U.N. Security Council. Under pressure from the United Nations mediators, Aristide agreed to the amnesty clause of the Governors Island Agreement. The Security Council immediately " declared [its] readiness to give the fullest possible support to the Agreement signed on Governors Island, " which it later said constitutes " the only valid framework for the resolution of the crisis in Haiti." When the military leaders initially failed to comply with the Governors Island Agreement, on July 31, 1994, the Security Council took the extreme step of authorizing an invasion of Haiti by a multinational force. On the eve of the invasion on September 18, 1994, a deal was struck, whereby General Cedras agreed to retire his command and accept exile in response to a general amnesty voted into law by the Haitian parliament and an offer by Panama to provide him asylum.

The amnesty deal had its desired effect: The democratically elected Aristide was permitted to return to Haiti and reinstate a civilian government, the military leaders left the country for sanctuary in Panama, much of the military surrendered their arms, and most of the human rights abuses promptly ended—all with practically no bloodshed or resistance. Although the situation in Haiti has once again deteriorated, with a wave of violent protests and strikes erupting in 2004, the more recent problems were due largely to President Aristide’s mismanagement and corruption, not the fact that the military leaders escaped punishment ten years earlier.

South Africa stands as another success story, indicating the potential value of trading justice for peace. From 1960 to 1994, thousands of black South Africans were persecuted and

mistreated under that country’s apartheid system. With the prospect of a bloody civil war looming over negotiations, " [t]he outgoing leaders made some form of amnesty for those responsible for the regime a condition for the peaceful transfer to a fully democratic society." The leaders of the majority black population decided that the commitment to afford amnesty was a fair price for a relatively peaceful transition to full democracy. In accordance with the negotiated settlement between the major parties, on July 19, 1995, the South African Parliament created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, consisting of a Committee on Human Rights Violations, a Committee on Amnesty, and a Committee on Reparation and Rehabilitation. Under this process, amnesty would be available only to individuals who personally applied for it and who disclosed fully the facts of their apartheid crimes. After conducting 140 public hearings and considering 20, 000 written and oral submissions, the South African Truth Commission published a 2739-page report of its findings on October 29, 1998. Most observers believe the amnesty in South Africa headed off increasing tensions and a potential civil war.

It is a common misconception that trading amnesty or exile for peace is equivalent to the absence of accountability and redress. As in the Haitian and South African situations described above, amnesties can be tied to accountability mechanisms that are less invasive than domestic or international prosecution. Ever more frequently in the aftermath of an amnesty- or exile-for- peace deal, the concerned governments have made monetary reparations to the victims and their families, established truth commissions to document the abuses (and sometimes identify perpetrators by name), and have instituted employment bans and purges (referred to as " lustration") that keep such perpetrators from positions of public trust. While not the same as criminal prosecution, these mechanisms do encompass much of what justice is intended to accomplish: prevention, deterrence, punishment, and rehabilitation. Indeed, some experts believe that these mechanisms do not just constitute " a second best approach" when prosecution is impracticable, but that in many situations they may be better suited to achieving the aims of justice.

B. Factors Favoring Prosecution

Although providing amnesty and exile to perpetrators may be an effective way to induce regime change without having to resort to force, there are several important countervailing considerations favoring prosecution that suggest amnesty/exile should be a bargaining tool of last resort reserved only for extreme situations. In particular, prosecuting leaders responsible for violations of international humanitarian law is necessary to discourage future human rights abuses, deter vigilante justice, and reinforce respect for law and the new democratic government. While prosecutions might initially provoke resistance, many analysts believe that national reconciliation cannot take place as long as justice is foreclosed. As Professor Cherif Bassiouni, then Chairman of the U.N. Investigative Commission for Yugoslavia, stated in 1996, " [i]f peace is not intended to be a brief interlude between conflicts, " then it must be accompanied

by justice.

Failure to prosecute leaders responsible for human rights abuses breeds contempt for the law and encourages future violations. The U.N. Commission on Human Rights and its Sub- Commission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities have concluded that impunity is one of the main reasons for the continuation of grave violations of human rights throughout the world. Fact finding reports on Chile and El Salvador indicate that the granting of amnesty or de facto impunity has led to an increase in abuses in those countries.

Further, history teaches that former leaders given amnesty or exile are prone to recidivism, resorting to corruption and violence and becoming a disruptive influence on the peace process. From his seaside villa in Calabar, Nigeria, for example, Charles Taylor orchestrated a failed assassination plot in 2005 against President Lansana Conte of Guinea, a neighboring country that had backed the rebel movement that forced Taylor from power.

What a new or reinstated democracy needs most is legitimacy, which requires a fair, credible, and transparent account of what took place and who was responsible. Criminal trials (especially those involving proof of widespread and systematic abuses) can generate a comprehensive record of the nature and extent of violations, how they were planned and executed, the fate of individual victims, who gave the orders, and who carried them out. While there are various means to develop the historic record of such abuses, the most authoritative rendering of the truth is possible only through the crucible of a trial that accords full due process. Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, the Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg, underscored the logic of this proposition when he reported that the most important legacy of the Nuremberg trials was the documentation of Nazi atrocities " with such authenticity and in such detail that there can be no responsible denial of these crimes in the future." According to Jackson, the establishment of an authoritative record of abuses that would endure the test of time and withstand the challenge of revisionism required proof of " incredible events by credible evidence."

In addition to truth, there is a responsibility to provide justice. While a state may appropriately forgive crimes against itself, such as treason or sedition, serious crimes against persons, such as rape and murder, are an altogether different matter. Holding the violators accountable for their acts is a moral duty owed to the victims and their families. Prosecuting and punishing the violators would give significance to the victims’ suffering and serve as a partial remedy for their injuries. Moreover, prosecutions help restore victims’ dignity and prevent private acts of revenge by those who, in the absence of justice, would take it into their own hands.

While prosecution and punishment can reinforce the value of law by displacing personal revenge, failure to punish former leaders responsible for widespread human rights abuses encourages cynicism about the rule of law and distrust toward the political system. To the victims of human rights crimes, amnesty or exile represents the ultimate in hypocrisy: While they struggle to put their suffering behind them, those responsible are allowed to enjoy a comfortable retirement. When those with power are seen to be above the law, the ordinary citizen will never come to believe in the principle of the rule of law as a fundamental necessity in a society transitioning to democracy.

Finally, where the United Nations or major countries give their imprimatur to an amnesty or exile deal, there is a risk that leaders in other parts of the world will be encouraged to engage in gross abuses. For example, history records that the international amnesty given to the Turkish officials responsible for the massacre of over one million Armenians during World War I encouraged Adolf Hitler some twenty years later to conclude that Germany could

pursue his genocidal policies with impunity. In a 1939 speech to his reluctant General Staff, Hitler remarked, " Who after all is today speaking about the destruction of the Armenians? " Richard Goldstone, the former Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, has concluded that " the failure of the international community to prosecute Pol Pot, Idi Amin, Saddam Hussein and Mohammed Aidid, among others, encouraged the Serbs to launch their policy of ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia with the expectation that they would not be held accountable for their international crimes." When the international community encourages or endorses an amnesty or exile deal, it sends a signal to other rogue regimes that they have nothing to lose by instituting repressive measures; if things start going badly, they can always bargain away their responsibility for crimes by agreeing to peace.

III. The Limited International Legal Obligation to Prosecute

In a few narrowly defined situations (described below) there is an international legal obligation to prosecute regardless of the underlying practical considerations. Where this is the case, failure to prosecute can amount to an international breach. An amnesty or asylum given to the members of the former regime could be invalidated in a proceeding before either the state’s domestic courts or an international forum. International support for such an amnesty or asylum deal would undermine international respect for and adherence to the treaties that require prosecution. Finally, it would be inappropriate for an international criminal court to defer to a national amnesty or asylum in a situation where the amnesty or asylum violates obligations contained in the very international conventions that make up the court’s subject matter jurisdiction.

A. Crimes Defined in International Conventions

The prerogative of states to issue an amnesty or grant asylum for an offense can be circumscribed by treaties to which the states are party. There are several international conventions that clearly provide for a duty to prosecute the humanitarian or human rights crimes defined therein, including in particular the grave breaches provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the Genocide Convention, and the Torture Convention. When these Conventions are applicable, the granting of amnesty or asylum to persons responsible for committing the crimes defined therein would constitute a breach of a treaty obligation for which there can be no excuse or exception. It is noteworthy, however, that these Conventions were negotiated in the context of the Cold War and by design apply only to a narrow range of situations, as such limitations were necessary to ensure widespread adoption.

1. The 1949 Geneva Conventions

The four Geneva Conventions were negotiated in 1949 to codify, inter alia, the international rules relating to the treatment of prisoners of war and civilians during armed conflict and in occupied territory after a war. Almost every country of the world is party to these conventions. Each of the Geneva Conventions contains a specific enumeration of " grave

breaches, " which are war crimes under international law for which there is individual criminal liability and for which states have a corresponding duty to prosecute or extradite. Grave breaches include willful killing, torture or inhuman treatment, willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, extensive destruction of property not justified by military necessity, willfully depriving a civilian of the rights of fair and regular trial, and unlawful confinement of a civilian.

Parties to the Geneva Conventions have an obligation to search for, prosecute, and punish perpetrators of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, or to hand over such persons for trial by another state party. The Commentary to the Geneva Conventions, which is the official history of the negotiations leading to the adoption of these treaties, confirms that the obligation to prosecute grave breaches is " absolute, " meaning, inter alia, that state parties can under no circumstances grant perpetrators immunity or amnesty from prosecution for grave breaches of the Conventions.

It is important to recognize that while states or international tribunals may prosecute persons who commit war crimes in internal armed conflicts, the duty to prosecute grave breaches under the Geneva Conventions is limited to the context of international armed conflict. Further, there is a high threshold of violence necessary to constitute a genuine armed conflict, as distinct from lower level disturbances such as riots, isolated and sporadic acts of fighting, or unilateral abuses committed by a government in the absence of widespread armed resistance by the target population. Moreover, to be an international armed conflict, the situation must constitute an armed conflict involving two or more states, or a partial or total occupation of the territory of one state by another.

In contrast to the duty to prosecute grave breaches occurring in an international armed conflict, with respect to internal armed conflict amnesties are not only permitted, but are encouraged by Article 6(5) of Additional Protocol II—a point the South African Constitutional Court stressed in finding that the amnesties granted by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission did not violate international law. The rationale for this provision is to encourage reconciliation, which is of greater importance in noninternational armed conflicts where patrolable international borders do not exist between former enemies. Thus, the Commentary on the Protocol, prepared by the International Committee of the Red Cross, states: " The object of this sub-paragraph is to encourage gestures of reconciliation which can contribute to reestablishing normal relations in the life of a nation which has been divided."

The Geneva Conventions, then, would require prosecution of Saddam Hussein for acts committed during the international armed conflicts involving Iran, Kuwait, and the 1991 Persian Gulf War. They would not, however, require prosecution of Charles Taylor, who is accused only of complicity in war crimes during the internal armed conflict in Sierra Leone.

2. The Genocide Convention

Most of the countries of the world are party to the Genocide Convention, which entered into force on January 12, 1952, and the International Court of Justice has determined that the substantive provisions of the Convention constitute customary international law binding on all states. Like the Geneva Conventions, the Genocide Convention provides an absolute obligation to prosecute persons responsible for genocide as defined in the Convention.

The Genocide Convention defines genocide as one of the following acts when committed " with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: "

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

There are several important limitations inherent in this definition. First, to constitute genocide, there must be proof that abuses were committed with the specific intent required by the Genocide Convention. It is not enough that abuses were intended to repress opposition; the intent must be literally to destroy a group of people. Second, and even more importantly, the victims of such abuses must constitute a group of one of the four specific types enumerated in the Genocide Convention, namely, national, ethnic, racial, or religious. In this respect, it is noteworthy that the drafters of the Genocide Convention deliberately excluded acts directed against " political groups" from the Convention’s definition of genocide.

The Genocide Convention would require prosecution of Saddam Hussein, who has been accused of ordering attacks aimed at destroying the Northern Iraqi Kurds and the Southern Iraqi Marsh Arabs as a people, resulting in hundreds of thousands of casualties. Charles Taylor, in contrast, has not been accused of acts of genocide.

B. The Torture Convention

The Torture Convention entered into force on June 26, 1987, and currently has 138 parties. The Convention defines " torture" as:

any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in or incidental to lawful sanctions.

The Torture Convention requires each state party to ensure that all acts of torture are offenses under its internal law and to establish its jurisdiction over such offenses in cases where the accused is found in its territory, and if such a state does not extradite the alleged offender, the Convention requires it to submit the case to its competent authorities for the purpose of prosecution. Persons convicted of torture are to be subjected to harsh sentences proportionate to the grave nature of the offense.

The Special Court for Sierra Leone charged Charles Taylor with committing crimes against humanity in Sierra Leone, including complicity in widespread and systematic acts of torture, from 1991–1999. Notably, however, neither Sierra Leone (the state where the acts of torture occurred), Liberia (the state of nationality of the accused), nor Nigeria (the state where

Charles Taylor was given asylum) were parties to the Torture Convention when the acts of torture in Sierra Leone were committed. And although the United States, which helped broker the exile-for-peace deal, was a party to the Torture Convention during that time, the requirements of the convention are not applicable to the United States in this case because the acts of torture did not occur in U.S. territory, the offender was not a national of the United States, and the offender was not present in U.S. territory. Under the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, the provisions of a treaty " do not bind a party in relation to any act or fact which took place... before the date of the entry into force of the treaty with respect to that party." Consistent with the Vienna Convention as well as the reasoning of the British High Court in the Pinochet case, the obligations to prosecute and to refrain from taking actions which would frustrate prosecution contained in the Torture Convention were not applicable to the case of Charles Taylor because his alleged involvement in acts of torture pre-dated the ratification of the Convention by the relevant states.

Still, some might argue that the Torture Convention is relevant to the situation involving Charles Taylor based on the Committee Against Torture’s 1990 decision concerning the Argentinean amnesty laws. In that case, the Committee Against Torture, which is the treaty body created by the Torture Convention to facilitate its implementation, decided that communications submitted by Argentinean citizens on behalf of their relatives who had been tortured by Argentinean military authorities were inadmissible since Argentina had ratified the Convention only after the amnesty laws had been enacted. However, in dictum, the Committee stated " even before the entry into force of the Convention against Torture, there existed a general rule of international law which should oblige all states to take effective measures to prevent torture and to punish acts of torture."

The Committee’s statement should not be mistakenly construed as suggesting that amnesties/asylum for persons who commit torture is invalid under customary international law. By using the word " should, " the Committee indicated that its statement was aspirational rather than a declaration of binding law. On the basis of its decision, the Committee urged Argentina to provide remedies for the victims of torture and their surviving relatives; it did not suggest that international law required that Argentina do so. Nor did it specify that the remedy should be prosecution of those responsible, rather than some other appropriate remedy such as compensation. The Committee’s decision, therefore, should not be read as indicating that the Torture Convention required Nigeria, Liberia, or Sierra Leone to prosecute those whose acts of torture pre-dated their ratification of the Convention.

4. General Human Rights Conventions

General human rights conventions include the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the similarly worded European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, and American Convention on Human Rights. Although these treaties do not expressly require states to prosecute violators, they do obligate states to " ensure" the rights enumerated therein. There is growing recognition in the jurisprudence of the treaty bodies responsible for monitoring enforcement of these conventions and the writings of respected commentators that the duty to ensure rights implies a duty to hold specific violators accountable.

Yet, a careful examination of the jurisprudence of these bodies suggests that methods of obtaining specific accountability other than criminal prosecutions would meet the requirement of " ensuring rights." This jurisprudence indicates that a state must fulfill five obligations in confronting gross violations of human rights committed by a previous regime:

(1) investigate the identity, fate, and whereabouts of victims; (2) investigate the identity of major perpetrators; (3) provide reparation or compensation to victims; (4) take affirmative steps to ensure that human rights abuse does not recur; and (5) punish those guilty of human rights abuse. Punishment can take many noncriminal forms, including imposition of fines, removal from office, reduction of rank, forfeiture of government or military pensions, and exile.

B. Crimes Against Humanity

1. Definition

As developed in the jurisprudence of the Nuremberg Tribunal and codified in the Statutes of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the Special Court for Sierra Leone, and the Rome Statute for the International Criminal Court, crimes against humanity are defined as:

any of the following acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack:

(a) Murder;

(b) Extermination;

(c) Enslavement;

(d) Deportation or forcible transfer of population;

(e) Imprisonment or other severe deprivation of physical liberty in violation of fundamental rules of international law;

(f) Torture;

(g) Rape, sexual slavery, enforced prostitution, forced pregnancy, enforced sterilization, or any other form of sexual violence of comparable gravity;

(h) Persecutions against any identifiable group or collectivity on political, racial, national, ethnic, cultural, religious, gender, or other grounds that are universally recognized as impermissible under international law, in connection with any act referred to in this paragraph or any crime within the jurisdiction of the Court;

(i) Enforced disappearance of persons;

(j) The crime of apartheid;

(k) Other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.

States are required to prosecute grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and the crime of genocide, but there exists no treaty requiring prosecution of crimes against humanity (except for torture where the state is party to the Torture Convention at the time the crime is

committed); crimes against humanity are purely a creature of customary international law. Traditionally, those who committed crimes against humanity were treated like pirates, as hostis humani generis (an enemy of all humankind), and any state, including their own, could punish them through its domestic courts. In the absence of a treaty containing the aut dedere aut judicare (extradite or prosecute) principle, this so called " universal jurisdiction" is generally thought to be permissive, not mandatory. Yet several commentators and human rights groups have recently taken the position that customary international law (and the notion of jus cogens — meaning peremptory norms) not only establishes permissive jurisdiction over perpetrators of crimes against humanity, but also requires their prosecution and conversely prohibits the granting of amnesty or asylum to such persons.

2. Customary International Law

Notwithstanding the chimerical conclusions of some scholars, there is scant evidence that a rule prohibiting amnesty or asylum in cases of crimes against humanity has ripened into a compulsory norm of customary international law. Customary international law, which is just as binding upon states as treaty law, arises from " a general and consistent practice of states followed by them from a sense of legal obligation" referred to as opinio juris. Under traditional notions of customary international law, " deeds were what counted, not just words." Yet those who argue that customary international law precludes amnesty/exile for crimes against humanity base their position on nonbinding General Assembly resolutions, hortative declarations of international conferences, and international conventions that are not widely ratified, rather than on any extensive state practice consistent with such a rule.

Commentators often cite the 1967 U.N. Declaration on Territorial Asylum as the earliest international recognition of a legal obligation to prosecute perpetrators of crimes against humanity. The Declaration provides that " the right to seek and enjoy asylum may not be invoked by any person with respect to whom there are serious reasons for considering that he has committed a... crime against humanity." Yet according to the historic record of this resolution, " [t]he majority of members stressed that the draft declaration under consideration was not intended to propound legal norms or to change existing rules of international law, but to lay down broad humanitarian and moral principles upon which States might rely in seeking to unify their practices relating to asylum." This evidences that, from the outset, the General Assembly resolutions concerning the prosecution of crimes against humanity were aspirational only, and not intended to create any binding duties.

In addition to this contrary legislative history, the trouble with an approach to proving the existence of customary international law that focuses so heavily on words is " that it is grown like a flower in a hot-house and that it is anything but sure that such creatures will survive in the much rougher climate of actual state practice." Indeed, to the extent any state practice in this area is widespread, it is the practice of granting amnesties or asylum to those who commit crimes against humanity. That the United Nations itself has felt free of legal constraints in endorsing recent amnesty and exile-for-peace deals in situations involving crimes against humanity suggests that customary international law has not yet crystallized in this area. The Special Court for Sierra Leone confirmed this when it recently held that domestic amnesties for crimes against humanity and war crimes committed in an internal armed conflict were not unlawful under international law.

Commentators may point to the Secretary General’s August 2004 Report to the Security Council on the Rule of Law and Transitional Justice as an indication that the United Nations has recently altered its position on the acceptability of amnesty/exile for peace deals. In that report, the Secretary-General of the United Nations said that peace agreements and Security Council resolutions and mandates should " [r]eject any endorsement of amnesty for genocide, war crimes, or crimes against humanity, including those relating to ethnic, gender and sexually based international crimes, [and] ensure that no such amnesty previously granted is a bar to prosecution before any United Nations-created or -assisted court." It is more significant, however, that in the Security Council’s debate on the Secretary-General’s Report, there was no consensus on this particularly controversial recommendation (only two of the fifteen members of the Council—Brazil and Costa Rica—spoke in favor of it while several opposed it), and the statement approved by the Council at the end of the debate made no reference to the issue of amnesty.

3. Jus Cogens

The concept of jus cogens —meaning " peremptory norms" —is said to be among the " most ambiguous and theoretically problematic of the doctrines of international law." Since the inception of the modern state system three and a half centuries ago, international law has been based on notions of consent. Under this concept of jus dispositivium (positive law), states were bound only to treaties to which they had acceded and to those rules of customary international law to which they had acquiesced. The concept of jus cogens, in contrast, is based in part on natural law principles that " prevail over and invalidate international agreements and other rules of international law in conflict with them."

Though the term itself was not employed, the jus cogens concept was first applied by the

U.S. Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which declared that the treaty between Germany and Vichy France approving the use of French prisoners of war in the German armaments industry was void under international law as contra bonus mores (contrary to fundamental morals). The debates within the U.N. International Law Commission, which codified the jus cogens concept in the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, reflect the view that the phenomenon of Nazi Germany rendered the purely contractual conception of international law insufficient for the modern era. Consequently, the International Law Commission opined that a treaty designed to promote slavery or genocide, or to prepare for aggression, ought to be declared void.

Thus, pursuant to the jus cogens concept, states are prohibited from committing crimes against humanity and an international agreement between states to facilitate commission of such crimes would be void ab initio. Moreover, there is growing recognition that universal jurisdiction exists such that all states have a right to prosecute or entertain civil suits against the perpetrators of jus cogens crimes. From this, some commentators take what they view as the next logical step and argue that the concept also prohibits states from undertaking any action that would frustrate prosecution, such as granting amnesty or asylum to those who have committed crimes against humanity.

Such scholars fail, however, to take into consideration the fact that although jus cogens has natural law underpinnings, the concept is also related to customary law. A rule will qualify as jus cogens only if it is " accepted by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted." Thus, jus cogens norms have been described by

one court as " a select and narrow subset of the norms recognized as customary international law." As with ordinary customary international law, jus cogens norms are formed through widespread state practice and recognition, but unlike ordinary customary international law, a state cannot avoid application of a jus cogens norm by being a persistent objector during its formation.

Though there is no question that the international community has accepted that the prohibition against committing crimes against humanity qualifies as a jus cogens norm, this does not mean that the associated duty to prosecute has simultaneously attained an equivalent status. In fact, all evidence is to the contrary. Not only have there been numerous instances of states providing amnesty and asylum to leaders accused of crimes against humanity, but, even more telling, there have been no protests from states when such amnesty or asylum has been offered. Moreover, there has been widespread judicial recognition that the jus cogens nature of crimes against humanity does not prevent accused perpetrators from successfully asserting head of state immunity or sovereign immunity to avoid criminal or civil liability in foreign courts. Because jus cogens, as a peremptory norm, would by definition supersede the customary international law doctrine of head of state immunity where the two come into conflict, the only way to reconcile these rulings is to conclude that the duty to prosecute has not attained jus cogens status.

As compared to the substantive rule of law prohibiting states from entering into international agreements that facilitate the commission of crimes against humanity, the procedural obligation of third parties to prosecute such crimes after their commission constitutes a far greater intrusion into a state’s internal sovereignty, with far less justification. Thus, it is sensible that such an encroachment would require the state’s consent through the carefully negotiated provisions of a treaty—such as the Geneva Conventions, Genocide Convention, or Torture Convention—which would narrowly define the applicable circumstances and perhaps— like the Rome Statute—provide escape clauses permitting states to disregard the obligation to prosecute when strict enforcement would frustrate greater interests of international peace and justice.

C. Amnesty/Exile and the International Criminal Court

The above discussion indicates that there are frequently no international legal constraints on the negotiation of an amnesty/exile-for-peace deal, and that in certain circumstances swapping amnesty/exile for peace can serve the interests of both peace and justice. However, an international criminal tribunal is not bound to defer to a domestic amnesty/exile arrangement. During the negotiations for the Rome Statute creating the International Criminal Court (ICC), the United States and a few other delegations expressed concern that the ICC would hamper efforts to halt human rights violations and restore peace and democracy in places like Haiti and South Africa.

According to the Chairman of the Rome Diplomatic Conference, Philippe Kirsch of Canada, the issue was not definitively resolved during the Diplomatic Conference. Rather, the provisions that were adopted reflect " creative ambiguity" that could potentially allow the prosecutor and judges of the ICC to interpret the Rome Statute as permitting recognition of an amnesty or asylum exception to the jurisdiction of the court.

1. The Preamble

The preamble to the Rome Statute suggests that deferring a prosecution because of the existence of a national amnesty or asylum deal would be incompatible with the purpose of the court, namely to ensure criminal prosecution of persons who commit serious international crimes. In particular, the Preamble:

Affirm[s] that the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole must not go unpunished and that their effective prosecution must be ensured...

Recall[s] that it is the duty of every State to exercise its criminal jurisdiction over those responsible for international crimes...

[And] Emphasiz[es] that the International Criminal Court established under this Statute shall be complementary to national criminal jurisdictions.

Preambular language is important because international law provides that " [a] treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose." Thus, the Rome Statute’s preamble constitutes a critical source of interpretation because it indicates both the treaty’s context and its object and purpose. Yet, notwithstanding this preambular language, there are several articles of the Rome Statute (discussed below) that might be read as permitting the court under certain circumstances to recognize an amnesty exception to its jurisdiction. The apparent conflict between these articles and the preamble reflects the schizophrenic nature of the negotiations at Rome: The preambular language and the procedural provisions were negotiated by entirely different drafting groups, and in the rush of the closing days of the Rome Conference, the drafting committee never fully integrated and reconciled the separate portions of the Statute.

2. Article 16: Action by the Security Council

With respect to a potential amnesty/asylum exception, the most important provision of the Rome Statute is Article 16. Under that article, the ICC would be required to defer to a national amnesty if the Security Council adopts a resolution under Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter requesting the court not to commence an investigation or prosecution, or to defer any proceedings already in progress. The Security Council recently invoked its right under Article 16 of the Rome Statute in adopting Resolution 1593, referring the Darfur atrocities to the ICC for prosecution but at the same time providing that the ICC could not exercise jurisdiction over foreign military personnel in Darfur who are from states (other than Sudan) that are not parties to the Rome Statute.

The Security Council has the legal authority to require the court to respect an amnesty or asylum if two requirements are met, namely: (1) the Security Council has determined the existence of a threat to the peace, a breach of the peace, or an act of aggression under Article 39 of the U.N. Charter; and (2) the resolution requesting the court’s deferral is consistent with the purposes and principles of the United Nations with respect to maintaining international peace and security, resolving threatening situations in conformity with principles of justice and international law, and promoting respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms under Article 24 of the U.N. Charter.

The decision of the Appeals Chamber of the Yugoslavia Tribunal in the Tadic case suggests that the ICC could assert that it has the authority to independently assess whether these two requirements were met as part of its incidental power to determine the propriety of its own jurisdiction (competence de la competence). One commentator has characterized this aspect of the Appeals Chamber decision as " strongly support[ing] those who see the U.N. Charter not as unblinkered license for police action but as an emerging constitution of enumerated, limited powers subject to the rule of law." It is possible, then, that the ICC would not necessarily be compelled by the existence of a Security Council resolution to terminate an investigation or prosecution were it to find that an amnesty contravenes international law.

While an amnesty or exile arrangement accompanied by the establishment of a truth commission, victim compensation, and lustration might be in the interests of justice in the broad sense, it would nonetheless be in contravention of international law where the grave breaches provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the Genocide Convention, or the Torture Convention are applicable. It is especially noteworthy that the Geneva Conventions require parties " to provide effective penal sanctions for persons committing, or ordering to be committed, any of the grave breaches of the present Convention, " that the Genocide Convention requires parties " to provide effective penalties for persons guilty of genocide, " and that the Torture Convention requires parties to make torture " punishable by appropriate penalties which take into account their grave nature."

This would suggest that the ICC might not defer to the Security Council under Article 16 of the Rome Statute where the accused is charged with grave breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the crime of genocide, or torture. Yet, a strong counterargument can be made that the Rome Statute codifies only the substantive provisions of the 1949 Geneva Conventions, the Genocide Convention, and the Torture Convention, and does not incorporate those procedural aspects of the Conventions that require prosecution (which apply to the state parties but not to the ICC, which has its own international legal personality). Accordingly, the nature of the charges might constitute a factor to be considered but would not necessarily be a bar to deferring to an amnesty or exile arrangement.

3. Article 53: Prosecutorial Discretion

Where the Security Council has not requested the ICC to respect an amnesty or exile- for-peace deal and thereby to terminate a prosecution, the court’s prosecutor may choose to do so under Article 53 of the Rome Statute. That article permits the prosecutor to decline to initiate an investigation (even when a state party has filed a complaint) where the prosecutor concludes there are " substantial reasons to believe that an investigation would not serve the interests of justice." However, the decision of the prosecutor under Article 53 is subject to review by the pretrial chamber of the court. In reviewing whether respecting an amnesty or exile deal and not prosecuting would better serve " the interests of justice, " the pretrial chamber would have to evaluate the benefits of a particular amnesty or exile arrangement and consider whether there is an international legal obligation to prosecute the offense (as discussed above).

4. Article 17: Complementarity

Where neither the Security Council nor the prosecutor has requested the ICC to defer to a national amnesty, the concerned state can attempt to raise the issue under Article 17(1)(a) of the Rome Statute. That article requires the court to dismiss a case where " [t]he case is being investigated or prosecuted by a State which has jurisdiction over it, unless the State is unwilling or unable genuinely to carry out the investigation or prosecution." It is significant that the article requires an investigation but does not specify that it be a criminal investigation. The concerned state could argue that a truth commission (especially one modeled on that of South Africa) constitutes a genuine investigation. On the other hand, subsection (2) of Article 17 suggests that the standard for determining that an investigation is not genuine is whether the proceedings are " inconsistent with an intent to bring the person concerned to justice" —a phrase that might be interpreted as requiring criminal proceedings.

* * *

In sum, the Rome Statute is purposely ambiguous on the question of whether the ICC should defer to an amnesty/exile-for-peace arrangement in deciding whether to exercise its jurisdiction. While amnesties and exiles are sometimes a necessary bargaining chip in negotiations for the peaceful transfer of political power, it must be recognized that such arrangements can vary greatly. Some, as in South Africa and Haiti, are closely linked to mechanisms for providing accountability and redress; others, as in the case of the exile of Charles Taylor, are simply a mindful forgetting. The ICC should take only the former types of amnesties/exiles into account in prosecutorial decisions. Moreover, the ICC should be particularly reluctant to defer to an amnesty/exile in situations involving violations of international conventions that create obligations to prosecute, such as the Genocide Convention and the grave breaches provisions of the Geneva Conventions. The other international agreements and customary international law crimes that make up the ICC’s subject matter jurisdiction make prosecution for related crimes possible, but not mandatory, and should be treated as such by the court in the broader interests of peace and international security.

IV. Conclusion

This Article has described how, under the present state of international law, the international procedural law imposing a duty to prosecute is far more limited than the substantive law establishing international offenses. The reason for this is historical: With respect to all but the most notorious of international crimes, it was easier for states to agree to recognize permissive jurisdiction than to undertake a duty to prosecute. But where the duty to prosecute does apply, it is critical that states and international organizations honor it, lest they express contempt for the important treaties from which the duty arises, potentially putting their own citizens at risk pursuant to the international law principle of reciprocity.

This is not to suggest, however, that states must rush to prosecute all persons involved in offenses under these treaties. Selective prosecution and use of " exemplary trials" is acceptable as long as the criteria used reflect appropriate distinctions based upon degrees of culpability and sufficiency of evidence. Moreover, while the provisions of the treaties requiring prosecution are nonderogable even in time of public emergency that threatens the life of the nation, the doctrine of force majeure can warrant temporary postponement of prosecutions for a reasonable amount of time until a new government is secure enough to take such action against members of the

former regime or until a new government has the judicial resources to undertake fair and effective prosecutions.

In the case of Saddam Hussein, the United States had accused the Iraqi leader of grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions and violations of the Genocide Convention. Both the United States and Iraq were parties to these treaties, which contain an absolute obligation to prosecute offenders. By offering to permit exile and perpetual sanctuary in Bahrain in lieu of invasion and prosecution, the Bush administration signaled that the provisions of these treaties are inconsequential, thereby undermining the rule of law in a critical area of global affairs. This must be viewed also in light of other U.S. actions involving application of the Geneva Conventions to the conflict in Iraq, most notably the infamous White House memos authored by now Attorney General Alberto Gonzales. The memos refer to the Geneva Conventions as " obsolete" and " quaint, " and wrongly opine that the Torture Convention permits mild forms of torture, thereby creating a climate of disdain toward international humanitarian law and opening the door to the abuses committed at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. In a statement before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Admiral John Hutson, Judge Advocate General of the U.S. Navy from 1997–2000, urged the Bush administration to officially and unequivocally repudiate Gonzales’s erroneous position. In doing so, Hutson stressed that:

Since World War II and looking into the foreseeable future, United States armed forces are more forward-deployed both in terms of numbers of deployments and numbers of troops than all other nations combined. What this means in practical terms is that adherence to the Geneva Conventions is more important to us than to any other nation. We should be the nation demanding adherence under any and all circumstances because we will benefit the most.

Because Hussein did not accept the exile-for-peace offer, the damage to the rule of law in this instance was negligible. Would greater damage to the rule of law have nevertheless been acceptable if it succeeded in averting a war which has resulted in tens of thousands of casualties on both sides since 2003? This Article has described the policy reasons generally favoring prosecution, including the fact that former leaders who have resorted to war crimes and crimes against humanity tend to be recidivists. Saddam Hussein himself launched a coup and initiated his policy of terror after he was released from prison through a domestic amnesty in 1968. It is not hard to imagine the dangers Hussein could present to the Iraqi democratic transition from exile in nearby Bahrain. Moreover, the people of Iraq have insisted on Hussein’s trial before the Iraqi Special Tribunal. Morally, what right would American negotiators have to trade away the ability of thousands of Hussein’s victims to see the dictator brought to justice? Finally, it is worth stressing that the duty to prosecute Hussein arising from these treaties did not require or even justify the invasion of Iraq. Rather, it merely prohibited actions that are manifestly incompatible with the prosecution of Hussein, such as arranging for exile and sanctuary in Bahrain.

The situation involving Charles Taylor is distinguishable. Taylor has been charged by the Special Court for Sierra Leone with complicity in crimes against humanity and war crimes in an internal armed conflict. As the Special Court itself has recognized, since there is no treaty- based nor customary international law duty to prosecute crimes against humanity or war crimes in an internal conflict, an amnesty or exile-for-peace deal would not constitute a violation of international law.

The distinction reflects the fact that, notwithstanding the natural law rhetoric of jus cogens employed by proponents of a broad duty to prosecute, the international legal order is still

governed by principles of positive law under the 357-year-old Westphalian concept of sovereignty. State practice belies the existence of a customary international law duty (based