Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Present culture and its elements. Provide examples and relate them to international business.

|

|

Culture gives people a sense of who they are, of belonging, of how they should behave, and of what they should be doing. Culture impacts behavior, morale, and productivity at work as well, and it includes values and patterns that influence company attitudes and actions. Culture is often considered the driving force behind human behavior everywhere.

Main elements:

- Material Culture

- Language

- Aesthetics

- Religion

- Social Institutions

Elements:

- Dress and Appearance. Many subcultures wear distinctive clothing: the formal look for business, the jeans of the youth throughout the world, and uniforms that segregate everyone from students to police, to.remen, to military generals. In the military subculture or microculture, customs and regulations determine the dress of the day, length of hair, and equipment to be worn;

- Communication and Language. English is used “link” language that is understood by two parties who speak different languages. For example, Japan-based Sony and Matsushita use English in their work abroad. Physical gestures, for example, often convey different meanings in different cultures: in Europe it is norm when woman shake hand to man, but not in Asia;

- Sense of Self and Space. The comfort one has with oneself can be expressed differently according to each culture. For example, Americans and the British have a sense of space that requires more distance between individuals, while Latins, Arabs, and the Vietnamese stand closer together;

- Food and Feeding Habits. The manner in which food is selected, prepared, presented, and eaten often differs by culture. For example, one man’s pet could be another person’s delicacy. For instance, pork, which is widely consumed by the Chinese, is forbidden in Muslim and Jewish cultures;

- Time and Time Consciousness. Sense of time differs by culture; some are exact and others are relative. Generally, Germans are precise about the clock,, time is a valuable and limited resource and when others do not come in time they lose their patience, while many Latins are more casual;

- Relationships. This refers to social structure, which embodies a culture’s fundamental organization including its groups and institutions, its system of social positions and their relationships, and the process by which its resources are distributed. The family unit is the most common expression of this characteristic.

For example, in Middle East countries parthers relate to each other better, if they know that person has family;

- Gender. For example greater gender

equality prevails in the United States, Australia, Canada, and Germany, but in countries operating under Islamic laws like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Afganistan there is contrary relationship to women in business.

35. What is the role of each major religion in conducting international business? What do Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, and Buddhism declare in terms of business?

- Christianity. Christianity is the most widely practiced religion in the world, with about 2 billion people identifying themselves as Christians and a vast majority of them living in the Americas and in Europe. importance of hard work and wealth creation and frugality, and this was the underlying value system that facilitated the development of capitalism. The combination of hard work by the Protestants and the accumulation of wealth for further expansion and investment s prepared the way for the development of capitalism in Europe and eventuallyin the United States.

- Islam. Islam is the second largest religion in the world and it has its roots in both Judaism and Christianity. Muslims believe that every human endeavor is within the framework of faith, because they believe that the only purpose of any activity is to do “inshallah, ” God’s will. In economic and.nancial terms, Islam allows people to make a pro.t, as long as that pro.t is earned justly and is not based on the exploitation of others. The pro.ts should also be used for charitable activities and for helping the poor. One economic principle in Islam prohibits the payment or receiving of interest, which is considered usury. For a Muslim the acceptance of interest payments is considered a sin. A characteristic feature of Islamic.nance is pro.t and loss that are based on Zakat, which derives from a social provision.11 Furthermore, these traditional concepts have created some contemporary institutions. The.rst Islamic Bank in the region was the Dubai Islamic Bank. When an Islamic bank lends money to a business, rather than charging that business interest on the loan, it takes a share in the pro.ts that are derived from the investment. Similarly, when a business deposits money at an Islamic bank in a savings account, the deposit is treated as an equity investment in whatever activity the bank uses the capital for. Consequently, the depositor receives a share in the pro.t from the bank’s investment.

- Hinduism. Many Hindus believe that the way to achieve nirvana is to lead a severe ascetic lifestyle of material and physical self-denial, devoting life to a spiritual rather than material quest.

Max Weber also argued that the ascetic principles found in Hinduism do not encourage the kind of entrepreneurial activity needed in the pursuit of wealth that is found in Protestantism. According to Weber, traditional Hindu values emphasize that individuals should not be judged by their material achievements, but by their spiritual achievements. Overall, we must be very careful not to read too much into Weber’s position, simply because there are millions of hardworking Hindu businessmen and -women in India who form the backbone of this country’s emerging economy.

- Buddhism. A Buddhist teaching is that if people have no desires, they will not suffer. This is important to marketers and production managers because if Buddhists and Hindus have no desires, they have little motive for achievement and for the acquisition of material goods. Today, Buddhism has approximately 360 million followers, mostly in nations such as China, Tibet, Korea, Vietnam, Thailand, and Japan.

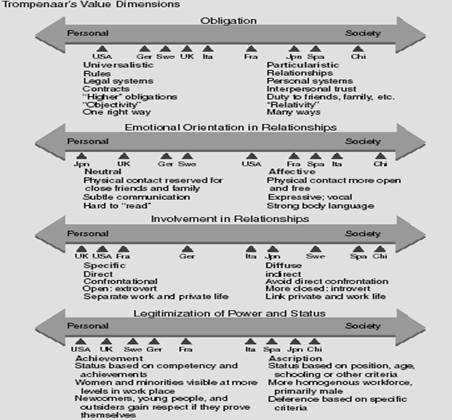

36. Describe Trompenaar’s value dimensions and discuss their use in international business.

There are 4 value dimensions, which are carried out on 2 levels-personal and society.

In Trompenaar’s dimension of universalism versus particularize, the universalistic approach applies rules and systems objectively, without consideration for individual circumstances, whereas the particularistic approach, more common in Asia and in Spain for example, not only puts the obligation toward relationships.rst but is also more subjective. Trompenaar found that people in particularistic societies are more likely to pass on inside information to a friend than those in universalistic societies.

In the neutral versus affective dimension, the focus is on the emotional orientation of relationships. The Italians, Mexicans, and the Chinese, for example, would openly express emotions even in a business situation whereas the British and the Japanese would consider such displays unprofessional; in turn they would be regarded as hard to “read.”

As for involvement in relationships, people tend to be either septic or diffuse (or somewhere along that dimension). Managers in septic-oriented cultures—United States, United Kingdom, France—separate work from personal issues and relationships; they compartmentalize their work and private lives and are more open and direct. In diffuse-oriented cultures like Sweden and China, there is a spillover from work into the realm of personal relationships and vice versa.

The achievement versus ascription dimension examines the source of power and status in society. In an achievement society, the source of status and impudence is based on individual achievement—how well one performs the job and what level of education and experience one has to offer. Therefore, women, minorities, and young people usually have equal opportunity to attain positions based on their achievements. In an ascription-oriented society, people ascribe status on the basis of class, age, gender, and so on; one is more likely to be born into a position of impudence. Hiring in Indonesia, for example, is more likely to be based on who you are than hiring for a position in Germany or Australia. From all this it becomes clear that a lot of what goes on at work can be explained by differences in people’s innate value systems. Awareness of such differences and how they impudence work behavior can be very useful to the international manager.

37. Compare and contrast the Kluckhohn–Strodtbeck and Hofstede frameworks and their application in understanding culture.

The analysis of both would assist international managers better understand the way organizations function within their own cultural framework.

The Kluckhohn–Strodtbeck framework compares cultures along six cultural dimensions. The following six questions assist the international manager in studying any given culture and in comparing it to a different one:

1. Do people believe that their environment controls them, that they control the environment, or that they are part of nature?

2. Do people focus on past events, on the present, or on the future?

3. Are people easily controlled and not to be trusted, or can they be trusted to act freely and responsibly?

4. Do people desire accomplishments in life, carefree lives, or spiritual lives?

5. Do people believe that individuals or groups are responsible for each person’s welfare?

6. Do people prefer to conduct most activities in private or in public?

Hofstede proposes four value dimensions:

1. Power distance

2. Uncertainty avoidance

3. Individualism

4. Masculinity

Power distance, the.rst value dimension, is the level of acceptance by a society of the unequal distribution of power in organizations. In the workplace, inequalities in power are normal, as evidenced in hierarchical boss–subordinate relationships. In countries in which people display high power distance (such as Malaysia, the Philippines, and Mexico), employees acknowledge the boss’s authority simply by respecting that individual’s formal position in the hierarchy, and they seldom bypass the chain of command. In countries where people display low power distance (such as Austria, Denmark, and Israel), superiors and subordinates are apt to regard one another as equal in power, resulting in more harmony and cooperation.

The second value dimension, uncertainty avoidance, refers to the extent to which people in a society feel threatened by ambiguous situations. Countries with a high level of uncertainty avoidance (such as Japan, Portugal, and Greece) tend to have strict laws and procedures to which their people adhere closely, and a strong sense of nationalism prevails. In a business context, this value results in formal rules and procedures designed to provide more security and greater career stability. Managers have a propensity for low-risk decisions, employees exhibit little aggressiveness, and lifetime employment is common. In countries with lower levels of uncertainty avoidance (such as Denmark, Great Britain, and, to a lesser extent, the United States), nationalism is less pronounced, and protests and other such activities are tolerated. Consequently, company activities are less structured and less formal, with some managers taking more risks, and there is high job mobility.

The third of Hofstede’s value dimensions, individualism, refers to the tendency of people to look after themselves and their immediate family only and neglect the needs of society. In countries that prize individualism (such as the United States, Great Britain, and Australia), democracy, individual initiative, and achievement are highly valued; the relationship of the individual to organizations is one of independence on an emotional level, if not on an economic level. In countries such as Pakistan and Panama where low individualism prevails—that is where collectivism predominates—one.nds tight social frameworks, emotional dependence on belonging to “the organization, ” and a strong belief in group decisions. People from a collectivist country, like Japan, believe in the will of the group rather than that of the individual, and their pervasive collectivism exerts control over individual members through social pressure and the fear of humiliation.

The fourth value dimension, masculinity, refers to the degree of traditionally “masculine” values—assertiveness, materialism, and a lack of concern for others—that prevail in a society. In highly masculine societies (e.g., Japan and Austria), women are generally expected to stay at home and raise a family. In organizations, one.nds considerable job stress, and organizational interests generally encroach on employees’ private lives. In countries with low masculinity (such as Switzerland and New Zealand), one.nds less con.ict and job stress, more women in high-level jobs, and a reduced need for assertiveness.

The four cultural dimensions proposed by Hofstede do not operate in isolation; rather they are interdependent and interrelated—and thus complex—in their impact on attitudes and behaviors within the work environment. Again, international managers must remember that the evaluation of an entire country on the basis of any one cultural value dimension is a generalization and thus a possible oversimpli.cation, for variations may occur according to subcultures, regions, and individuals.

38. What is parochialism? Culture shock? Ethnocentrism? Provide examples.

Parochialism occurs when a German, for example, expects those from or in another country to automatically fall into patterns of behavior common in Germany. Ethnocentrism describes the attitude of those who operate from the assumption that their ways of doing things are best no matter where or under what conditions they are applied. Aggressive ethnocentrism results in serious and large-scale violation of rights based on origin, gender, language and religion. Africa has played scene to many of these ethnic uprisings and genocide (conflicts).

Culture shock refers to the anxiety and feelings (of surprise, disorientation, uncertainty, confusion, etc.) felt when people have to operate within a different and unknown cultural or social environment, such as a foreign country. It grows out of the difficulties inassimilating the new culture, causing difficulty in knowing what is appropriate and what is not. This is often combined a dislike for or even disgust (moral or aesthetical) with certain aspects of the new or different culture.

39. What are the phases of the culture shock? Explain the methods of dealing with culture shock

Honeymoon Phase - During this period the differences between the old and new culture are seen in a romantic light, wonderful and new. For example, in moving to a new country, an individual might love the new foods, the pace of the life, the people's habits, the buildings and so on.

Negotiation Phase - After some time (usually weeks), differences between the old and new culture become apparent and may create anxiety. One may long for food the way it is prepared in one's native country, may find the pace of life too fast or slow, may find the people's habits annoying, disgusting, and irritating etc. This phase is often marked by mood swings caused by minor issues or without apparent reason. Depression is not uncommon.

Adjustment Phase - Again, after some time (usually 6 - 12 months), one grows accustomed to the new culture and develops routines. One knows what to expect in most situations and the host country no longer feels all that new. One becomes concerned with basic living again, and things become more " normal".

Reverse Culture Shock (a.k.a. Re-entry Shock) - Returning to one's home culture after growing accustomed to a new one can produce the same effects as described above, which an affected person often find more surprising and difficult to deal with as the original culture shock.

Methods:

1) Know that it is a normal part of adjusting to a new culture and that others are or have experienced it too.

2) Learn the language. Being fluent will take time and practice, but you’ll never get there if you don’t start. Don’t be ashamed to cary a dictionary around with you. If people know you are trying it’s amazing how helpful they can be.

3) Join the gym, an organization, or take classes. All of these things will force you to get out of the house and interact with others. Plus if you are used to being in shape then getting sluggish will just add to your depression.

4) Be realistic. You aren’t going to conquer a new culture in a day. And even once you think you’ve overcome your culture shock, you’ll still have your bad days. But didn’t that even happen at home?

5) Become a regular and learn key people who can help. If your grocer or a certain clerk at the post office knows you, it’s likely that he/she will give you helpful hints and help you with the language as well. They will be proud when you start speaking to them in their native tongue.

6) Learn as much about the culture before you go as you can. Do you know people from the place you are going or people who have spent time there in the past? Listen to their stories. Ask questions. And don't doubt their experiences. Don't think " Well that may have happened to you, but it won't happen to me" because chances are, it will.

40. What do we mean by cross-cultural management and training?

Cross-cultural means A critical skill that international business managers must have is a working

knowledge of the cultural variables that could influence their managerialdecisions. Although training in language and practical affairs is quite straightforward, cross-cultural training is not; it is complex and deals with deep-rooted behaviors. The actual process of cross-cultural training should result in the expatriate learning both content and skills that will improve interactions with host-country individuals, thus reducing misunderstandings and inappropriate behaviors.

41. How employers can help bridge the cultural divide in the workplace? [1]

· Learn as much as you can about the culture of the people you are dealing with, particularly if you employ several people from the same cultural background.

· Recognize the broad ethnic diversity that exists within groups such as Hispanics or Asians. Don’t assume everyone shares common cultural backgrounds or languages just because they came from the same region of the world. Someone labeled “Hispanic” may come from the mountains of Chili, a large Central American city or a rural village in Mexico. The same is true for immigrants from the many different Asian countries where cultures and languages vary widely.

· Respect individual differences, abilities and personalities. Even though people may share a common language or culture, it doesn’t mean they are alike, any more than all Americans are alike. Stereotyping discounts individuals and can limit options for them in the workplace. Getting to know a person’s culture is a first step to getting to know them as individuals.