Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Methods of Examination. Complaints.The main complaints with intestinal diseases are pain, meteorism (inflation of the abdomen)

|

|

Inquiry

Complaints. The main complaints with intestinal diseases are pain, meteorism (inflation of the abdomen), motor dysfunction of the intestine (constipation and diarrhoea), and intestinal haemorrhage.

Pain. If the patient complains of pain in the abdomen, the following should be established: location of pain, its radiation, intensity, character, duration, and means by which it is lessened. The general signs by which intestinal pain may be differentiated from gastric one are: (1) absence of regular dependence of pain on food taking; the only exception is inflammation in the transverse colon (transversitis): pain develops immediately after meals; the pathogenesis of this pain is connected with reflex peristaltic contractions of the transverse colon when food enters the stomach; (2) close association of pain with defaecation: pain occurs before, during, and (rarely) after defaecation; (3) pain relief after defaecation or passage of gas.

Pain may be boring and spasmodic (intestinal colic). Colicky pain is characterized by short repeated attacks which arise and disappear quite of a sudden. Pain may very quickly change its location, the main site being

round the navel. Sometimes pain may arise in other areas of the abdomen. Boring pain is sometimes permanent; it intensifies during cough, especially if the mesenterium or peritoneum are involved. Pain is characteristic of inflammatory diseases of the intestine. As inflammation extends onto the peritoneum, pain is attended by a pronounced muscular defence.

Exact location of the source of pain is very important. Pain in the right iliac region occurs in appendicitis, tuberculosis, cancer, or inflammation of the caecum (typhlitis). Acute pain in the left lower abdomen occurs in intestinal obstruction and inflammation of the sigmoid (sigmoiditis). Pain in the umbilical region occurs in inflammation of small intestine (enteritis) and inflammation or cancer of the colon. Pain in the perineal region, and especially during defaecation (with the presence of blood in faeces), is characteristic of the rectum diseases (proctitis, cancer). Pain in intestinal pathology may radiate into the chest; pain associated with affection of the spleen angle of the descending large intestine radiates into the left side of the chest (it is sometimes mistaken for pain attacks of angina pectoris); colics of appendicitic origin radiate into the right leg.

In acute affection of the left portions of the large intestine (dysentery), pain radiates into the sacral area. Thermal procedures, spasmolytics, passage of gas, and emptying of the bowels can relieve pain or remove it completely.

Intestinal pain is caused by obstruction of intestinal patency and upset motor function. Intestinal pain is mostly caused by spasms (spasmodic contraction of smooth muscles; hence spastic pain), or by distension of the intestine by gases. Both mechanisms often become involved.

Spastic pain can be due to various causes. Individual predisposition to spastic contractions in general (vegetoneurosis) may be as important as irritation originating in the intestine proper, e.g. in enteritis, colitis, intestinal tumour, poisoning with arsenic or lead, and also in diseases of the central nervous system (posterior spinal sclerosis).

Pain arising due to intestinal distension by gases, and associated with tension and irritation of the mesentery, differs from spastic pain (1) by the absence of periodicity; it is long-standing and gradually lessens in prolonged inflation; and (2) by exact localization. In intestinal obstruction (complete or partial) colicky pain is combined with almost permanent pain in the abdomen. It is characterized by exact and permanent location (the umbilical region and large intestine). The pain intensifies with intestinal peristalsis.

Appendicular colic first localizes round the navel and the epigastrium

but in several hours (or even on the next day) it descends to the right iliac

region where it intensifies gradually. Sometimes the pain arises straight in

the right iliac region.; '

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

Rectal colic, or tenesmus, is also known. It occurs in frequent and painful tenesmus to defaecate and is associated with spasmodic contractions of the intestine and the sphincter ani. Only clots of mucus are sometimes expressed instead of actual defaecation. Tenesmus occurs in dysentery and other inflammatory or ulcerous diseases, and in cancer of the rectum. Pain associated with defaecation depends on many factors. Pain preceding defaecation is associated with the disease of the descending colorf or sigmoid colon. Pain during defaecation is characteristic of haemorrhoids, anal fissures, and cancer.

Rectal colic, or tenesmus, is also known. It occurs in frequent and painful tenesmus to defaecate and is associated with spasmodic contractions of the intestine and the sphincter ani. Only clots of mucus are sometimes expressed instead of actual defaecation. Tenesmus occurs in dysentery and other inflammatory or ulcerous diseases, and in cancer of the rectum. Pain associated with defaecation depends on many factors. Pain preceding defaecation is associated with the disease of the descending colorf or sigmoid colon. Pain during defaecation is characteristic of haemorrhoids, anal fissures, and cancer.

Meteorism. The patient feels flatulence, inflation, and boring distension of the abdomen. The causes of meteorism are (1) excessive gas formation in the intestine due to ingestion of vegetable cellular tissue and easily fermented food (peas, beans, cabbage, etc.); (2) intestinal motor dysfunction due to decreased tone of the intestinal wall or intestinal obstruction; (3) lowered absorbability of gases by the intestinal wall, the process of gas formation being normal; (4) aerophagia, i.e. excess swallowing of air, with its subsequent propulsion to the stomach and the intestine; (5) hysterical meteorism: the abdomen is rapidly inflated to the size of the abdomen of a pregnant woman at her last weeks; this nervous mechanism is very complicated.

When inquiring the patient, the physician should ask about the character of his nutrition and the site of abdomen inflation (the entire abdomen or only its limited part may be inflated). If inflation is local, it is necessary to ask the patient whether or not inflation occurs always at one and the same area. In intestinal obstruction, the patient feels rumbling sounds inside the abdomen, feels movement of liquid in the intestine, and intense peristaltic movements above the point of obstruction.

Diarrhoea. Frequent and liquid stools is a common sign of intestinal pathology. Diarrhoea occurs in acute and chronic intestinal infections (enteritis, enterocolitis, sigmoiditis, proctitis), in various exogenous intoxications (poisoning with arsenic or mercury), endogenous intoxications (uraemia, diabetes, gout), in endocrine disorders (adrenal dysfunction, thyrotoxicosis), and in hypersensitivity to some foods (allergy).

The mechanism of diarrhoea is very complicated. Different pathogenic factors may prevail in various pathological conditions. Accelerated movement of the liquefied food in the intestine due to peristalsis is among them. Almost undigested food can thus be evacuated. Another factor is disordered absorptive function of the intestine. Affection of the intestinal wall, disordered mechanisms regulating absorption, purgatives and upset water metabolism produce a marked change in the absorption process and are the cause of diarrhoea.

The third cause of liquid stools is inflammation of the intestine. Large

quantities of inflammatory secretion stimulating the intestinal receptors are released into the lumen of the intestine to intensify its peristalsis and to impair its absorptive function.

Paradoxical diarrhoea occurs in prolonged constipation due to mechanical irritation of the intestinal wall by hard faecal masses.

Upset equilibrium between the fermentative and putrefactive flora of the intestine is another important factor in the aetiology of diarrhoea. If fermentative flora prevails, fermentative dyspepsia occurs which is characterized by flatulence of the abdomen and semiliquid acid faeces (2— 3 stools a day); the faeces contain numerous gas bubbles, numerous starch grains, vegetable cellular tissue, and iodophilic microbes. Fermentative dyspepsia develops in connection with deranged digestion of carbohydrates, if they are ingested in excess.

Putrid dyspepsia more often occurs in secretory hypofunction of the stomach. The absence of bactericidal action of gastric juice is connected with the absence of hydrochloric acid; rapid passage of insufficiently digested food from the stomach to the intestine has a negative effect in the first instance on digestion of proteins. This in turn provokes putrid dyspepsia. It is characterized by liquid dark excrements containing clots of undigested food; the faeces react alkaline and have a foul putrid smell. Microscopy of faeces reveals much fats, muscular fibres with vivid transverse and longitudinal striation and even ends (creatorrhoea). The content of organic compounds in the faeces is increased. The iodophilic flora is absent.

Diarrhoea occurring in organic affections of the large intestine is mostly of the inflammatory character. It is not copious, nor does it produce strong negative effect on the patient's general condition (as compared with affections of the small intestine which is attended by profuse diarrhoea associated with deranged motor and absorption function of the intestine). The pronounced disorder in digestion causes some metabolic disorders in the patient (impaired absorption of proteins, iron, vitamins, and electrolytes).

Obstipation. This is obstinate constipation during which faeces are long retained in the intestine (for more than 48 hours). But the duration of constipation is only relative, because in many cases it is not the result of pathology but of the living conditions and nutrition. If vegetable food dominates in the diet, the subject may defaecate two or three times a day. Stools become rarer if the diet is rich in meat. A radical change in nutrition can remove constipation. Limited mobility of the subject, hunger, and irregular defaecations (during the day) may prolong pauses between defaecation. The main factor determining defaecation is the condition of intestinal motor function. Bowel contents are retained in the large intestine and the rectum during constipation.

Special Part f

Chapter 7. Digestive System

Organic and functional constipation is differentiated. Organic constipation is usually associated with mechanical obstruction, such as narrowing of the intestinal lumen due to a tumour, scar, adhesion, and also abnormalities in the intestine (megacolon, dolichosigmoid, megasigmoid, diverticulosis).

Organic and functional constipation is differentiated. Organic constipation is usually associated with mechanical obstruction, such as narrowing of the intestinal lumen due to a tumour, scar, adhesion, and also abnormalities in the intestine (megacolon, dolichosigmoid, megasigmoid, diverticulosis).

Functional constipation is subdivided into: (1) alimentary constipation; it occurs due to ingestion of easily assimilable foods, which leave small residue and normally stimulate peristalsis of the intestine by irritating its nervous receptors; (2) neurogenic constipation due to dysfunction of the intramural nervous apparatus or vagus nerve; these are the so-called dyskinetic constipation, caused by the reflex action on the intestinal motor function of another affected organ (cholecystitis, adnexitis, prostatitis, etc.), or by organic affections of the central nervous system (tumours of the brain, encephalitis, posterior spinal sclerosis); (3) constipation associated with inflammatory affections, mainly of the large intestine (dysentery); (4) toxic constipation occurring in exogenous poisoning with lead, morphine, or cocaine; (5) constipation of endocrine aetiology, occurring in thyroid or pituitary hypofunction; (6) constipation caused by lack of physical exercise; (7) constipation caused by flaccidity of the prelum.

Intestinal haemorrhage often occurs in ulcerous affections of the alimentary system. It develops in the presence of tumour, protozoal and helminthic invasions, acute infections (typhoid fever, bacillary dysentery), in thrombosis of mesenteric vessels, ulcerous non-specific colitis, etc.

Anamnesis. The patient should be inquired thoroughly about his nutrition from his early childhood till the onset of the disease (especially directly before the disease), about poisonings in the past history and hypersensitivi-ty to some feods. It is necessary to find out if the patient's meals are regular, if the food is varied, and if the patient smokes or drinks alcohol. Information on the past diseases of the intestine and also on pathology of other organs is sometimes decisive for establishing the cause of the present affection.

Some functional disorders of the intestine can be associated with occupation (lead or arsenic poisoning, constipation due to frequent suppression of tenesmus to defaecate).

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

Severe prolonged affection of the absorptive function causes grave cachexia. Oedema is possible in loss of protein with simultaneous retention in the body of water and salt. Inspection of the skin reveals its dryness and pallidness; the mucosa is pale due to insufficient absorption of iron and anaemization of the patient. Insufficient absorption of vitamins results in

development of fissures of the lips, the skin becomes rough and perleche develops.

Facies hippocratica (facies abdomihalis) is a very important diagnostic sign of peritonitis or intestinal obstruction. The tongue in intestinal diseases often becomes crimson (cardinal tongue), its papillae are smoothed down. The gums may be loose and bleeding.

Inspection of the abdomen. The general outlines of the abdomen should be inspected. The abdomen can be of a normal shape with slightly protruding suprapubic region; it can be enlarged due to excess subcutaneous fat, and inflated in the presence of meteorism or ascites. Regularity of the abdomen shape should be assessed. An enlarged liver may protrude in the upper abdomen; an enlarged uterus causes protrusion of the lower abdomen.

The patient is asked to breathe " with his abdomen" to assess the mobility of the abdominal wall. The patient is unable to take a deep breath in the presence of pain, e.g. in an attack of acute appendicitis or cholecystitis. Divarication of the rectus abdominis muscles can be revealed if the patient raises his head. Regular application of hot-water bottle leaves its traces on the abdomen; these, together with postoperative scars, often help the physician to interpret correctly the present patient's complaints. Antiperistaltic movements in the epigastrium or by the course of the intestine can give a hint on the presence of an obstacle to propulsion of food masses in the intestine.

If the abdomen is inflated, the causes should be established. These may be obesity, accumulation of liquid, or meteorism. Slight distension of the abdomen may be due to a tumour, encapsulated fluid, or meteorism associated with intestinal stenosis. The latter suggestion is confirmed by visible peristalsis over the constricted portion of the intestine where the flatulence is observed.

PALPATION

Palpation of the abdomen. Along with X-ray examination, palpation is the main method of physical examination in diagnosis of diseases of the abdominal organs. This method was first appreciated by French physicians (Glenard). Later the Russian internists (Obraztsov, Strazhesko, and others) further developed this useful method.

Glenard proposed palpation of the abdomen and believed that this method should systematically be used for clinical examination of the abdominal cavity. He maintained that palpation can be used to examine not only the abdominal organs but also various portions of the intestine. Having established that the caecum, transverse colon, sigmoid, and the colon proper can sometimes be palpated, he erroneously believed that their palpability indicated

25-1556

_„.,..., ui.pciiuently of Glenard, Obraztsov developed methods for palpation of the gastro-intestinal tract and proved that some parts of the stomach and the intestine can be palpated in the absence of any pathology. He gave a detailed description of physical properties of each part of the abdominal organs in normal conditions. He thus substantiated usefulness of palpation in clinical practice along with other physical methods of examination; secondly he stimulated the study of the topographic relationships in the abdominal cavity of a living person before X-rays were discovered; and thirdly his teaching made it possible to compare the physical properties of organs and their topographic relations in health with those in pathology, which has become an important tool in the diagnosis of diseases of the abdominal cavity.

_„.,..., ui.pciiuently of Glenard, Obraztsov developed methods for palpation of the gastro-intestinal tract and proved that some parts of the stomach and the intestine can be palpated in the absence of any pathology. He gave a detailed description of physical properties of each part of the abdominal organs in normal conditions. He thus substantiated usefulness of palpation in clinical practice along with other physical methods of examination; secondly he stimulated the study of the topographic relationships in the abdominal cavity of a living person before X-rays were discovered; and thirdly his teaching made it possible to compare the physical properties of organs and their topographic relations in health with those in pathology, which has become an important tool in the diagnosis of diseases of the abdominal cavity.

Later Obraztsov and his pupils developed in detail palpation techniques for examination of the abdominal cavity; they studied the organs and their separate parts that can be palpated under various conditions, and also gave a detailed description of normal palpatory signs of organs and their changes in various pathological conditions. They have proved finally the importance of palpation as an invaluable method of examination of the abdominal organs. It should however be emphasized that it is very difficult to master properly the palpation techniques for diagnostic purposes. It requires much experience and training. The palpation method described below has been proposed by Obraztsov and Strazhesko.

It is necessary that the abdominal cavity should be accessible to palpation, i.e. that its muscles (prelum) be relaxed and that the examiner should not provoke their straining by his manipulations. The patient should relax in his bed. (The bed should not be too soft.) His legs should be stretched and the arms flexed on the chest. The patient's breathing should not be deep; his head should rest against a small firm pillow. This position ensures relaxation of the abdominal muscles. The physician takes his place by the right side of the bed, facing the patient. The chair should be firm and level with the patient's bed. The ambient temperature should be comfortable for the patient, and the hands of the doctor should be warm and dry.

The examining movements should be careful and gentle so as not to hurt the patient. Touching the abdomen roughly with cold hands will cause reflex contraction of the prelum to interfere with palpation of the abdomen. The patient with distended abdomen should first be given cathartics or enema to empty the bowels. These are the conditions for palpation of the patient in the recumbent position. But some organs or their parts can only be palpated when they hang by gravity with the patient in the erect position. Thus the left lobe of the liver, the lesser curvature of the stomach, the spleen, the kidneys, the caecum, or tumours can become palpable. The epigastrium and the lateral parts of the abdominal cavity should also be palpated with the patient in the erect position.

Palpation is used to establish normal topographic relations between the abdominal organs and their normal physical condition; the other object is to detect any possible pathology that changes the morphological condition of the organs and their topographic relations responsible for their dysfunction, to locate the defect, and to determine its nature. Surface and deep

Chapter 7. Digestive System 37

palpation are used. Deep palpation gives information on the physical am sometimes functional condition of the organs and also on their position ir the abdominal cavity. In other words, deep palpation gives information on the topography of the abdominal cavity (topographic palpation).

Surface tentative palpation. The physician assumes his position by the bedside as described above and places his right hand flat on the abdomen of the patient (the fingers may be slightly flexed) to examine carefully and gradually the entire abdomen without trying to penetrate the deep parts of the abdomen. By this examination the physician should establish the strain of the prelum, its tenderness, and location of the painful site. The left inguinal area should be examined first, provided the patient does not complain of pain in this region. Palpation is then continued by examining symmetrical points of the abdomen on its left and right sides to end in the epigastric region. If the patient complains of pain in the left inguinal area, the sequence of palpation should be so changed that the least painful site on the anterior abdomen should first be examined. The physician should simultaneously assess the condition of the abdominal skin and subcutaneous connective tissue, the strain of the abdominal wall, the zones of superficial and deeper painful areas to locate them accurately. Hernial separation of muscles and protrusions, and also other anatomical changes should be revealed, if any. Resistance and marked strain of muscles of the abdominal wall are usually palpated over the organ affected by inflammation, especially so if the peritoneum is involved. In the presence of acute inflammation of the peritoneum (local inflammation included, e.g. in purulent appendicitis, cholecystitis, and the like), local pressure causes strong pain but it becomes even more severe when the pressure is released (Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom). In the presence of pronounced enlargement of the parenchymatous organs, in strained abdomen or intestinal loops, and also in the presence of large tumours, even surface palpation can give much diagnostic information. But only deep systematic palpation can give full information about the condition of the abdominal cavity and its organs, as well as their topography.

Deep sliding palpation (according to Obraztsov and Strazhesko). When starting deep palpation the examiner should always be aware of the anatomical relations in the abdominal cavity, the shape and physical properties of the organs, their supporting structures and possible deviations in topographical relations that may depend on the constitution of the patient, his special condition, nutrition, relaxation of the abdominal muscles, etc.

Obraztsov used the double-checking principle in his examinations. For example, in order to make sure that a given section of the intestine is actually ileum terminale it is necessary to locate the caecum; to determine the size of the stomach, the palpatory findings are checked by percussion

25*

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

percussive palpation of the stomach. Respiratory excursions of the organs should be taken into consideration during palpation according to a strictly predetermined plan, beginning with more readily accessible parts. The following sequence is recommended: the sigmoid, the caecum with the appendix, pars coecalis ilii, the ascending and descending colon, the stomach with its parts, the transverse colon, the liver, the spleen, the duodenum, the pancreas, and the kidneys.

percussive palpation of the stomach. Respiratory excursions of the organs should be taken into consideration during palpation according to a strictly predetermined plan, beginning with more readily accessible parts. The following sequence is recommended: the sigmoid, the caecum with the appendix, pars coecalis ilii, the ascending and descending colon, the stomach with its parts, the transverse colon, the liver, the spleen, the duodenum, the pancreas, and the kidneys.

Success of palpation depends on strict observation of the rules. The posture of the patient and the physician should be the same as in surface palpation. Palpation should be carried out by the apt hand. In some cases the other hand should be placed on the examining hand to increase pressure. Palpation can also be bimanual (palpation with both hands simultaneously). If only one hand is used, the other hand presses the prelum laterally to the palpated zone in order to lessen or overcome resistance of the abdominal wall and hence to promote relaxation of the prelum in the palpated zone. The other hand can be used to move the palpated organ closer to the examining hand or in order to perform bimanual palpation.

The palpation technique includes the following four steps. First: proper positioning of the physician's hands. The right hand is placed flat on the anterior abdominal wall, perpendicular to the axis of the examined part or the edge of the examined organ. Second: formation of a skin fold to facilitate further movements of the examining hand. Third: moving the hand inside the abdomen. Deep palpation is when the fingers are moved gradually, with each expiration, into the abdomen when the abdominal wall is relaxed. The examining hand thus reaches the posterior wall of the abdomen or the underlying organ. Fourth: sliding movement of the fingertips in the direction perpendicular to the transverse axis of the examined organ. The organ is pressed against the posterior wall and the examining fingers continue moving over the examined intestine or the stomach curvature. Depending on the position of the organ, the sliding movement should be either from inside, in the outward direction (the sigmoid, caecum) or in the downward direction (the stomach, transverse colon); the movements should then be more oblique in accordance with the deviation of the organ from the horizontal or vertical course. The examining hand should always move together with the skin and not over its surface.

By palpating the intestine, the physician establishes its localization, mobility, tenderness, consistency, diameter, the condition of the surface (smooth, tubercular), the absence or presence of rumbling sounds during palpation. All these signs indicate the presence or absence of pathology.

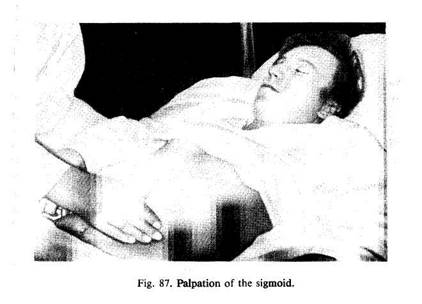

The sigmoid (Fig. 87) is palpated from top right to medial left, downward and laterally, perpendicularly to the axis of the intestine which

runs obliquely in the left iliac space at the border of median and the outer third of the linea umbilico-iliacae. Palpation is carried out by four fingers, placed together and slightly flexed, or by the ulnar edge of the right little finger. The fingers are immersed medially of the expected position of the intestine and as soon as the posterior wall of the abdomen is reached, the fingers slide along the intestine in the given direction, i.e. laterally and downward. The intestine is pressed against the posterior wall and first slides along it (to the extent allowed by the mesenteric length) but later it slips from under the examining fingers. The sigmoid can be palpated by the described technique in 90-95 per cent of cases. The sigmoid is only impalpable in excess inflation of the abdomen and in obese patients. If the sigmoid is not found where it belongs, it may be displaced to some other location because of long mesenterium which accounts for the high sigmoid mobility. It is then usually displaced closer to the navel and to the right. The sigmoid can usually be found by deep palpation of the infraumbilical and suprapubic areas. Normally the sigmoid can be palpated over the length of 20-25 cm as a smooth firm cylinder, its thickness being that of a thumb or an index finger; the sigmoid is painless to palpation, it does not produce rumbling sounds, its peristalsis is rather flaccid and infrequent. The sigmoid can be displaced 3-5 cm to either side.

The caecum is palpated by the same technique (Fig. 88), except that the direction is different. Since the caecum is situated at the border of the median and lateral third of the umbilico-iliac line (5 cm by the iliac spine), the

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

Fig. 88. Palpation of the caecum.

palpation is carried along this line or parallel to it. Palpation is used not only to locate the caecum but also a certain part of the ascending colon (10—12 cm of its length), i.e. the part of the large intestine which is known in the clinic as typhlon. A normal caecum can be palpated in 80-85 per cent of cases as a moderately strained cylinder (widening to the round bottom), 2-3 cm in diameter; when pressed upon, it rumbles. Palpation is painless. It reveals a certain passive mobility of the caecum (to 2—3 cm). The lower-edge of the caecum is 0.5 cm above the bi-iliac in man and 1-1.5 cm below it in women. Further palpation of the right iliac region gives (in 80—85 per cent of cases) information on the 15—20 cm length of the ileum which ascends from the small pelvis to the right, to be connected with the large intestine (ileum terminale). This section of the intestine extends mostly upward and to the right and palpation should therefore be carried out almost parallel to the umbilico-iliac line (but below it). The terminal end of the ileum can be palpated in the depth of the right iliac space as a soft, easily peristalting and passively mobile cylinder, the thickness of the little finger (or a pencil); it slips out from under the examining fingers and rumbles distinctly. When the terminal end of the ileum is found, the vermiform process can be found above or below it. It is found easier if the belly of the psoas muscle is first found. The location of this muscle is facilitated when the patient slightly raises his straight right leg. The vermiform process then becomes more pronounced over the contracted belly of the psoas muscle. The vermiform process can be palpated in 20—25 per

cent of cases. This is a thin (goose-feather thick) painless cylinder. When palpated the process does not change its consistency; nor does it rumble. Once the cylinder has been felt above or below the ileum, the examiner cannot be quite sure that he has found the vermiform process because it can be simulated by mesenteric duplicature and a lymph bundle. It is difficult to find the vermiform process also because its position varies with respect to the caecum. It becomes impalpable at all when located behind the caecum. When the process is inflamed it becomes much easier to find it because of its thickening, fixation, and consolidation. The caecum, the terminal part of the ileum, and the vermiform process are palpated by four fingers of the right hand; the fingers should be held together and slightly flexed. If the prelum is tense, the muscles in the palpation zone can be relaxed by pressing the umbilical area with the radial edge of the left hand.

The ascending and descending colons are palpated by two hands (Fig. 89). The left hand is placed under the left and then the right lumbar side, while the fingers of the right hand press on the anterior wall of the abdominal cavity until the examiner feels his right and left hands meet. The examining fingers then slide laterally, perpendicularly to the axis of the intestine (Vasilenko).

The transverse colon is palpated by four fingers of the right hand held together and slightly flexed (Fig. 90). Bimanual palpation can also be used. Since the position of the transverse colon is unstable, it is useful first to determine by percussive palpation (after Obraztsov) the lower border of

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

| |

|

|

Fig. 90. Palpation of the transverse colon.

the stomach, and only then to search for the colon some 2—3 cm below this border. The right hand (or both hands) is placed on the sides of the linea alba and the skin is moved slightly upwards. The examining hand is then immersed gradually during relaxation of the prelum at expiration until the posterior wall of the abdomen is felt. Once the posterior wall is reached, the examining hand should slide down to feel the intestine: this is an arching (transverse) cylinder of moderate density (2—2.5 cm thick), easily movable up and down, painless and silent. If the intestine is impalpable in this region, the same technique should be used to examine the lower and lateral regions, the position of the palpating hands being changed accordingly. Normal transverse colon can be palpated in 60—70 per cent of cases.

In addition to the mentioned portions of the intestine, the horizontal parts of the duodenum and the curvature of the colon can in rare cases be palpated; an occasional loop of the small intestine that may happen in the iliac cavity can also be palpated. But the small intestine is usually impalpable because of its deep location, high mobility, and thin walls; it cannot be pressed against the posterior abdominal wall, which is the necessary condition for palpation of normal intestine.

The rectum can be probed by a finger after cleansing it with enema. The patient should assume the knee-chest position. The examining index finger should first be coated with vaseline oil and then introduced carefully into the rectum to the maximum possible depth. If the patient is especially sensitive, or the rectum and the ampulla are affected with inflammation or

fissures, the sphincter and the ampulla should be anaesthetized before the intervention. As the examining finger passes the sphincter, it feels anteriorly the prostate in men and the vaginal part of the uterus in women. The finger should be moved upwards to pass the sacrococcygeal plica and to reach, if possible, the terminal rectal plica that closes the entrance to the sigmoid (11-13 cm above the anus). Palpation of the rectum can be facilitated if the patient squats and strains (makes evacuatory efforts). After examination of the anterior wall, the posterior wall of the rectum is felt by the finger. The finger is turned through 180° and the posterosacral and then lateral walls are examined. The examiner should get an idea of the mucosa (the presence of papilloma, polyps, varicose nodes, oedema and swelling of the mucosa, cicatricial narrowings, newgrowths, etc.) and the connective tissue surrounding the rectum, Douglass space, the prostate, the uterus and its appendages, and the pelvic bones.

Palpability of tumours of the abdominal cavity gave the impetus to detailed and systematic development of palpation techniques. This method is still important for the diagnosis of tumour. Palpation is used to reveal a tumour, to determine its belonging and relation to the neighbouring organs. Palpation is now sometimes carried out under roentgenoscopic control. Once a tumour has been revealed, it is necessary to establish its location: whether it is located in the abdominal wall proper, inside the abdominal cavity, or behind the peritoneum. If a tumour is present in the abdominal cavity, it is necessary to determine the organ to which it relates and also its relation to other organs; mobility of the tumour should then be determined, and also the presence of inflammatory process in the peritoneum round the tumour.

As distinct from intra- and retroperitoneal tumours, tumours of the abdominal wall are located more superficially and can easily be revealed by inspection. When the prelum is strained the tumour becomes fixed and its palpation becomes more difficult but it does not disappear from the palpation field, as is the case with intraperitoneal tumours (during respiratory excursions, intraperitoneal tumours move anteroposteriorly because the prelum protrudes during inspiration and retracts during expiration).

Tumours located behind the peritoneum are in close contact with the posterior abdominal wall; their mobility is low during respiration or palpation; moreover, they are always covered by the intestine or the stomach. Retroperitoneal tumours are characterized by high respiratory and passive mobility. The closer they are located to the diaphragm, the greater their vertical mobility during inspiration. The width and length of the overlying ligaments of the organ to which the tumour is related determine passive mobility of the tumour. But sometimes tumours of fastened parts of the gastro-intestinal tract become highly mobile due to congenital excessively long mesenterium and ligaments, or due to distension of the supporting apparatus by the growing tumour. For example, pyloric tumours or tumours of the caecum are highly mobile. Intraperitoneal tumours lose their respiratory and passive mobility if inflammation of the surrounding peritoneum develops with formation of firm adhesions between the tumour and the neighbouring organs.

Detecting a tumour and locating it inside the abdomen is the first stage in its identification. Next determined are its shape, density, elasticity, features of the surface, the presence of fluctuation, tenderness, and relation to a particular organ. This becomes only possible after preliminary topographic palpation of the entire abdominal cavity and establishment of the position and properties of each separate organ. This concrete study of topographic relations is necessary because, due to the growth of a tumour and changed intra-abdominal pressure,

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

these relations are often upset and perverted and knowledge of the normal position of the organs and their relation to each other is no more useful.

these relations are often upset and perverted and knowledge of the normal position of the organs and their relation to each other is no more useful.

Every physician must be able to perform methodic palpation in order to treat patients with pathologies of the abdominal organs. This may be an internist, a surgeon, a gynaecologist, or a urologist.