Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Increased pressure in the left atrium increases pressure in the pulmonary veins and this in turn causes reflex contraction of the arterioles 3 страница

|

|

Essential hypertension is characterized by periodically recurring transient elevations of arterial pressure (hypertensive crisis). Development of such crises is preceded by psychic traumas, nervous overstrain, variations in atmospheric pressure, etc.

Hypertensive crisis develops with a sudden elevation of the arterial pressure that can persist from a few hours to several days. The crisis is attended by sharp headache, feeling of heat, perspiration, palpitation, giddiness, piercing pain in the heart, sometimes by deranged vision, nausea, and vomiting. In severe crisis, the patient may lose consciousness. The patient is excited, haunted by fears, or is indifferent, somnolent, and inhibited. Auscultation of the heart reveals accentuated second sound over the aorta, and also tachycardia. The pulse is accelerated but can remain unchanged or even decelerated; its tension increases. Arterial pressure increases significantly. ECG shows decreased S-T interval and flattening of the T wave. In the late stages of the disease, with organic changes in the vessels, cerebral circulation may be deranged during crisis; myocardial infarction and acute left-ventricular failure may also develop.

Classification. According to Myasnikov, three stages of the disease are classified; each stage is further divided into two phases, A and B.

The A phase of the first stage is latent; it is characterized by elevated arterial pressure during a psychic stress, while under normal conditions arterial pressure is normal. The B phase is transient (transitory hypertension); arterial pressure increases only occasionally and under certain conditions; objective changes are absent.

In the second stage, arterial pressure is elevated permanently and more significantly. Phase A is characterized by permanent but unstable

hypertension. Subjective sensations are pronounced; hypertensive crises are possible; spasms of the cerebral and coronary arteries are likely to occur as well. Signs of hypertrophy of the left ventricle develop. Phase B is characterized by a significant and stable elevation of the arterial pressure. Hypertensive crises are frequent. Paroxysms of angina pectoris and derangement of cerebral circulation of the angiospastic character occur. Changes in the fundus oculi and pronounced signs of hypertrophy of the left ventricle can be revealed.

During the third stage, sclerotic changes in the organs and tissues are /t! iti/^observed along with stable and marked elevation of the arterial pressure. A is compensated. Arteriosclerosis of the kidneys is observed, but

renal function is not upset significantly. Cardiosclerotic changes do not stable heart failure; and sclerosis of cerebral vessels is not attended by pronounced disorders in the cerebral circulation. Phase B is decompensated, with grave dysfunction of various organs and with renal insufficiency; cerebral circulation is disordered and hypertensive retinopathy is observed. In this stage of the disease, the arterial pressure may normalize after infarction or apoplectic stroke.

Treatment. Complex therapy is required; Reasonable work should be alternated with rest, sufficient sleep, and remedial exercises. Sedatives should be given to improve sleep and to normalize excitation and inhibition processes. Hypotensive preparations (rauwolfia, ganglioblocking preparations, magnesium sulphate) are prescribed to inhibit the increased activity of the vasomotor centres and the synthesis of nor adrenaline. Diuretics (saluretics) are given to decrease intracellular sodium; aldosterone blocking agents (spironolactone) and other preparations are also given.

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is a chronic disease characterized by systemic affection of arteries due to metabolic disorders in the vascular wall. Atherosclerosis is one of the most common diseases and the most frequent cause of disability and premature death. It usually attacks people over 40-45 but sometimes occurs in younger patients. The incidence of atherosclerosis in men is 3-4 times higher than in women.

Aetiology. The aetiology of the disease is uncertain. It has been established that atherosclerosis occurs in subjects who undergo long nervous and psychic overstrain, hypodynamia, who suffer from overeating (taking much food rich in animal fats) and obesity, and diabetes mellitus, or myxoedema. The pathogenesis of the disease is complicated and not clear. It is believed that the function of a complicated neurohumoral apparatus regulating metabolism becomes upset by some causal factors. As a

Special Part

Chapter 6. Blood Circulatory System

result, biochemical, physico-chemical, and morphological composition of the blood is affected along with impairment of the blood coagulation system, disorders of structure, biochemistry and function of the arteries, and of their permeability. Hereditary predisposition to atherosclerosis is important in some cases.

result, biochemical, physico-chemical, and morphological composition of the blood is affected along with impairment of the blood coagulation system, disorders of structure, biochemistry and function of the arteries, and of their permeability. Hereditary predisposition to atherosclerosis is important in some cases.

Pathological anatomy. The changes are localized in large elastic arteries, i.e. in the aorta, the coronary, cerebral, renal arteries and the large arteries of the limbs.

The atherosclerotic process occurs in stages. First, lipids are deposited in the arterial in-tima to form fat spots and strips, which do not rise above the surface of the intima. Later, connective tissue grows in the region of lipid accumulation to form a fibrous atherosclerotic plaque which rises above the intima surface to narrow the lumen of the vessel. The lipid-protein complex inside the plaque can decompose to ulcerate its surface and to form an atheromatous ulcer. The ulcerated plaques can become the cause of thrombosis of the vessel and calcification of the fibrous plaques, which causes even greater changes in the arterial walls.

Clinical picture. The disease may be asymptomatic for years (pre-clinical period). Study of the blood during this period shows increased cholesterol or beta-lipoprotein content. The further picture of the disease depends on the affection of particular vessels (aorta, coronary arteries of the heart, cerebral vessels, renal arteries, and the limb arteries). This is the clinical period of the disease, which is divided into three stages, namely the ischaemic stage, during which ischaemic changes occur in the organs (e.g. angina pectoris attacks occur in atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries); the second or thrombonecrotic stage, characterized by thrombosis in the changed arteries (myocardial infarction may occur at this stage); and the third, fibrous stage, characterized by the development of connective tissue in the organs (e.g. cardiosclerosis).

Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries (see " Angina Pectoris", " Myocardial Infarction" and " Cardiosclerosis").

Aortic atherosclerosis usually occurs in individuals aged over 40, but even its grave forms can sometimes be asymptomatic. Atherosclerosis of the ascending aorta and its arch occurs more frequently. The patient feels pressing or burning pain in the retrosternal region which radiates in both arms, the neck, the back, and the upper abdomen. As distinct from pain in angina pectoris this pain is more persistent; it can continue for hours and even days, with periodic weakening and strengthening. The elastic properties of the aorta decrease and the heart has to perform greater work, which causes hypertrophy of the left-ventricular myocardium. Inspection of the heart reveals increased apex beat and its displacement to the left; on percussion, the borders of dullness of the vascular bundle are expanded. Retrosternal pulsation can be palpated in the jugular fossa because of the high standing of aortic arch (due to its elongation). The first heart sound is

as a rule dull, the second sound is heard over the aorta; systolic murmur is also found which appears or becomes intensified when the patient raises his arms (Sirotinin-Kukoverov symptom). Systolic murmur is due to both sclerotic narrowing of the aortic orifice and roughness of the inner surface of the aorta. Maximum arterial pressure increases, while minimum pressure either remains unchanged or slightly falls. X-ray study reveals straightened, dilated, and elongated aorta. Atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta is rarely diagnosed during life.

Atherosclerosis of the mesenteric arteries impairs blood supply to the intestine and may cause attacks of angina abdominis: the patient suddenly feels (3-6 hours after meals) piercing pain in the upper abdomen or in the umbilical region, which persists from 2 or 20 minutes to 1-2 hours. The pain is attended by the swelling of the abdomen, regurgitation, constipation, palpitation, and increased arterial pressure. In thrombosis of mesenteric arteries, the intestinal loops begin necrotizing, which is manifested by haemorrhage and paralytic intestinal obstruction.

Atherosclerosis of the renal arteries causes vascular nephrosclerosis, which is manifested by hypertension and isohyposthenuria.

Atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries is manifested by decreased work capacity (mental in particular), impaired memory, decreased active concentration, and rapid fatigue. The patient complains of insomnia and giddiness. The behaviour of the patient with pronounced atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries changes: he becomes fussy, selfish, fidgety, and captious; his mental power decreases. Atherosclerosis of the cerebral arteries is complicated by disturbed cerebral circulation (haemorrhage, thrombosis).

Atherosclerosis of the limb arteries. Clinical signs of this disease are pain in the gastrocnemius muscles during walking. The pain is very severe and the patient has to stop for a while, but as he proceeds with walking, the pain soon develops again (intermittent claudication). The patient feels chill and cold in the legs. Examination of the legs reveals the absense of pulse (or weak pulse) on the dorsalis pedis artery and the posterior tibial artery. Dry gangrene of the lower extremities develops in grave cases due to local circulatory disorder. Angiography of the affected vessels reveals deformation, tortuosity, narrowing of the lumen, and microaneurysms.

Treatment. Combined therapy is aimed at removal of nervous effects, normalization of metabolic processes by prescribing rational diet and appropriate medicinal preparations to control the lipid content (lecithin, vitamin C, nicotinic acid, miscleron—2—3 capsules a day per os for several months, in courses, etc.).

Rational diet, correct alternation of work and rest, regular exercise,

quiet at home and at work are important conditions for prophylaxis of

atherosclerosis., -..., ■..........,., ,..,...............

21-1556

Special Part

Chapter 6. Blood Circulatory System

Ischaemic Heart Disease

Ischaemic Heart Disease

The term ischaemic heart disease includes many diseases, such as angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, and coronary cardiosclerosis. The pathology is based on insufficient blood supply to the heart. The disproportion between the heart's demand for blood and the actual blood supply may arise when the heart's demands increase significantly, or when the actual blood supply diminishes for some reasons.

Angina Pectoris

Angina pectoris is a frequently occurring disease. Its main clinical symptoms are attacks of retrosternal pain due to acute but transient disorder in the coronary circulation. The disease develops mainly in people over 40, and predominantly in men. Mental workers would mostly suffer from this disease.

Aetiology and pathogenesis. The most frequent cause of angina pectoris is atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries of the heart. Much less frequently it develops in infectious and infectious-allergic vascular diseases, such as syphilitic aortitis, panarteritis, periarteritis nodosa, rheumatic vasculitis, and obliterating endarteritis. Angina pectoris often concurs with essential hypertension. Paroxysms of angina pectoris may develop due to upset nervous regulation of the coronary arteries as a reflex or in cholelithiasis, hiatus hernia, diseases of the stomach, etc. by reflex. Spasms of the coronary arteries (without their anatomical changes) can sometimes provoke angina pectoris. The spasm may develop in heavy smokers or as a result of a strong emotional stress.

Hypoxaemia (ischaemia) of the myocardium provokes the attack. Ischaemia develops in conditions when the insufficient amount of blood is delivered to the heart muscle through the coronary arteries, and the myocardium does not receive the necessary amount of oxygen. Transient oxygen hunger causes a reversible disorder in the oxidation-reduction processes in the myocardium. Stimulation of the interoceptors of the myocardium or the vascular adventitia by the products of upset metabolism produces a current of impulses via the centripetal pathways to the cerebral cortex to cause the specific symptom of the disease, retrosternal pain. High activation of the sympatheticoadrenal system is also very important for the onset of angina pectoris.

Pathological anatomy. No organic changes are sometimes found in those who died from an attack of angina pectoris. But in 85—90 per cent of cases signs of atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries pronounced to a different degree are discovered.

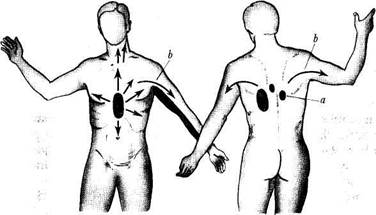

Clinical picture. The main clinical symptom of the disease is pain in the centre of the sternum (retrosternal pain). Less frequently the pain originates in the heart region. The character of pain varies: the patient may feel constriction, compression, heaviness, burning, and sometimes sharp or stabbing pain. Pain is usually severe and the patient develops morbid fear of death. Pain radiates into the left shoulder, left arm, left side of the neck and the head, the mandible, the interscapular space, and sometimes to the upper abdomen (Fig. 81). The characteristic radiation of pain during angina pectoris is due to hypersensitivity of the patient's skin to pain in the zones innervated by the 7th cervical and lst-5th thoracic segments of the spinal cord (Zakharyin-Head zones). Stimuli from the heart are transmitted through these segments to the centrifugal nerves of the spinal cord (by the viscerosensory reflex). Pain arises under certain conditions: during walking (especially fast walking) and other exercises (angina pectoris of effort).

|

| Fig. 81. Localization and radiation of pain in angina pectoris: Zakharyin-Head zone (a); nerve pathways of pain radiation (b). |

During physical exertion, the heart muscle requires more nutrition from blood. Atherosclerotic vessels cannot deliver the appropriate amount of blood and the patient has to stop exercise (walking) for a few minutes until pain subsides. Specific sign of angina pectoris is development of pain when the patient leaves a warm room and walks in the open during cold seasons. The symptom is even more pronounced if atmospheric pressure changes. Under emotional stress, the patient develops an attack of angina pectoris without any exercise. Attacks of pain may occur during sleep (angina pectoris at rest), after meals, in abdominal distention, and in high diaphragm.

Special Part

Chapter 6. Blood Circulatory System

Pain may last from few seconds to 20-30 min. Quick removal of pain after taking nitroglycerin suggests angina pectoris.

The strength of attacks differs. In rare cases attacks end lethally. During an attack, the pulse is usually slow and rhythmical, but tachycardia, ex-trasystole, and increased arterial pressure are sometimes observed. Percussion and auscultation of the heart sometimes cannot reveal any abnormality, provided pronounced atherosclerotic cardioslecrosis is absent. The body temperature remains normal. Usually there are no changes in the peripheral blood.

Electrocardiographic studies during attacks of angina pectoris sometimes reveal signs of disordered coronary circulation: the S-T segment is low, the two-phase or negative T wave is small in standard leads, and also in the corresponding chest leads, depending on the localization of affection in the coronary system. When the attack is abated, the electrocardiographic picture soon normalizes, ECG can sometimes reveal the described changes only during physical load. Coronarography with contrast substances is sometimes carried out to reveal occlusion of the coronary arteries.

Course. The disease is chronic. Attacks can be rare, once a week or even less frequently; attacks may be absent for months or even years, or their frequency may increase and they become more severe. An attack of angina pectoris lasting more than 30-60 minutes can end in myocardial infarction. Patients with long-standing angina pectoris develop car-diosclerosis; the cardiac rhythm becomes disordered and symptoms of heart failure develop.

Treatment. Depending on the gravity of the course, four functional classes of angina pectoris are distinguished. The first class is characterized by rare attacks and they occur only during physical exertion; in the second and third classes tolerance to exercise decreases progressively, while patients with the fourth class develop attacks of angina pectoris during slight exercise or even at rest. Vasodilatory preparations are given during attacks of angina pectoris and measures taken to prevent new attacks. The most effective preparation to remove pain is nitroglycerin: 1-3 drops of a 1 per cent alcohol solution placed on a lump of sugar or a tablet (both should be kept under the tongue). The effect of nitroglycerin becomes appreciable usually in 1—2 minutes. The patient with angina pectoris should always keep nitroglycerin by himself. Mustard plaster or leeches on the heart are also effective.

In order to remove frequent and severe attacks of pain and to prevent myocardial infarction, a surgical method of treatment is now used by which the coronary arteries are by-passed.

.

Sedatives (valerian, motherwort, trioxazin, etc.) in combination with vasodilatory preparations are regularly given to prevent attacks of angina pectoris.

Myocardial Infarction

Myocardial infarction is formation of a necrotic focus in the heart muscle due to upset coronary circulation. Myocardial infarction occurs mainly in people over 45; the incidence in men is higher than in women.

Aetiology. One of the main causes of myocardial infarction (in at least 90-95 per cent cases) is atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries. In exceptionally rare cases, myocardial infarction is secondary to embolism of the coronary vessel in endocarditis or septic thrombophlebitis, in inflammatory affections of the coronary arteries such as rheumatic coronaritis, obliterating endarteritis, and nodular periarteritis. Overstrain, both physical and nervous, overeating, alcohol and nicotin poisoning can also provoke myocardial infarction.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of myocardial infarction is complicated and has not been sufficiently studied. According to current views, several factors are responsible for the onset of the disease. The main of them is believed to be coronary thrombosis and stenotic coronary sclerosis. Coronary thrombosis develops due to local changes in the vascular wall which are characteristic of atherosclerosis, and also as a result of disorders in the blood coagulating system which are manifested by the decreased blood content of heparin and decreased fibrinolytic activity. In the absence of thrombosis, intense work of the heart in conditions of decreased blood supply to the myocardium (stenotic coronary sclerosis) is very important for the development of myocardial infarction. According to other investigators, the main factor responsible for myocardial infarction are functional disorders in the coronary circulation which provoke a prolonged spasm in the coronary arteries or their paresis. In their opinion atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries promotes development of myocardial infarction. Certain researchers believe that electrolyte imbalance in the heart muscle and accumulation of catecholamines in it and some other factors are important for the development of myocardial infarction.

Pathological anatomy. When blood supply to a part of the myocardium becomes inadequate, ischaemia develops, which is followed by necrosis. Inflammatory changes then develop round the necrotized area, and granular tissue grows. Necrotized mass is resorbed and replaced by cicatricial tissue. The heart muscle may rupture at the site of necrosis with haemorrhage into the pericardial sac (heart tamponade). In gross myocardial infarction the scar tissue may be so thin that it can swell to give cardiac aneurysm. Myocardial infarction usually develops in the left ventricle. Muscle layers located beneath the endocardium are usually involved in the

Special Part

Chapter 6. Blood Circulatory System

necrotic process (subendocardial form), but in severe cases, the entire muscle is involved (transmural infarction). Fibrinous pericarditis usually arises in such cases. Fibrin is sometimes deposited on the inner membrane of the heart at sites corresponding to myocardial necrosis (parietal thromboendocarditis). Thrombotic masses may be torn off and carried by the blood to account for embolism of the cerebral, abdominal, lung, and other vessels. According to the size of the necrotized focus, micro- and macrofocal myocardial infarctions are differentiated.

necrotic process (subendocardial form), but in severe cases, the entire muscle is involved (transmural infarction). Fibrinous pericarditis usually arises in such cases. Fibrin is sometimes deposited on the inner membrane of the heart at sites corresponding to myocardial necrosis (parietal thromboendocarditis). Thrombotic masses may be torn off and carried by the blood to account for embolism of the cerebral, abdominal, lung, and other vessels. According to the size of the necrotized focus, micro- and macrofocal myocardial infarctions are differentiated.

Clinical picture. The outstanding Russian physicians Obraztsov and Strazhesko were the first to describe the clinical picture of myocardial infarction in 1909; they differentiated between three variants of its course, namely, anginous, asthmatic, and abdominal (gastralgic) forms.

The anginous form occurs most frequently; clinically it is characterized by the pain syndrome. Pressing pain behind the sternum or in the region of the heart develops, like in angina pectoris. As a rule, pain radiates into the left shoulder and the left arm; less frequently into the right shoulder. Pain is sometimes so severe that cardiogenic shock develops which is characterized by the increasing weakness and adynamia, paleness of the skin, cold sweat, and decreased arterial pressure. As distinct from angina pectoris, pain in myocardial infarction is not removed by nitroglycerin and persists for longer time (from 30—60 minutes to several hours). Prolonged pain in myocardial infarction is termed as status anginosus.

The asthmatic form begins with an attack of cardiac asthma and lung oedema. The main syndrome is either absent or weak.

The abdominal form of myocardial infarction is characterized by pain in the abdomen, mostly in the epigastric region. The pain may be attended by nausea, vomiting, and constipation (gastralgic form of myocardial infarction). This form of the disease occurs mostly in infarction of the posterior wall of the left ventricle.

Further observations have shown that the disease has considerably greater number of clinical signs. Myocardial infarction may sometimes begin with a sudden heart failure or collapse, various disorders in the cardiac rhythm or heart block, while the pain syndrome is either absent or is weak (painless form). This course often develops in recurrent infarction. The cerebral form of the disease is characterized by disorders in the cerebral circulation of various intensity.

Examination of the cardiovascular system reveals enlargement of cardiac dullness and low percussion sounds. The gallop rhythm can sometimes be heard. Pericardial friction is audible over a limited area, in the 3rd-4th interspaces, in transmural myocardial infarction. Pericardial friction becomes audible on the second or third day of the disease and persists for a few hours or may last one or two days. Pulse in myocardial infarction is often small, accelerated, or arrhythmical (in affection of the conduction system). Arterial pressure increases during pain attacks but then it falls.

Depending on the localization of infarction, circulation may be disordered by the left-ventricular or (less frequently) right-ventricular type. In the former case, congestive moist rales can be heard in the lungs; asphyxia resembling cardiac asthma may develop, which is then followed by oedema of the lungs. In the latter case, the heart is enlarged to the right; the liver is enlarged too; the lower extremities are affected by oedema.

Fever and leucocytosis develop on the second or third day of the disease. They result from reactive processes which depend on absorption of the autolysis products from the site of infarction. The larger the necrotized area, the higher is the temperature and the longer the pyretic period and leucocytosis. Elevated temperature persists for 3-5 days, sometimes 10 days and more; ESR begins increasing and leucocytosis decreases from the second week of the disease.

Diagnosis of myocardial infarction depends substantially on the determination of activity of some blood serum enzymes which are released due to necrotic changes in the myocardium, e.g. the activity of creatine phosphokinase, the first and the fifth enzymes of lactic dehydrogenase, aminotransferase, and especially asparagine and (to a lesser degree) alanine increase by the end of the first day of the disease. The activity of creatine phosphokinase normalizes in 2—3 days, of aminotransferase in 4—5 days, and of lactic dehydrogenase in 10—14 days.

Electrocardiographic examination is especially important. It establishes the presence of myocardial infarction and also some important details of the process such as localization, depth of the process, and the size of the affected area (Fig. 82).

The S-T segment and T wave change during the first hours of the disease. The descending limb of the R wave transforms into the S-T segment without reaching the isoelectric line. The S-T segment rises above the isoelectric line to form a con vexing arch and to coincide with the T wave. A monophase curve is thus formed. These changes usually persist for 3—5 days. Then the S-T segment gradually lowers to the isoelectric line while the T wave becomes negative and deep. A deep Q wave appears, the R wave becomes low or disappears at all. The QS wave is then formed, whose appearance is characteristic of transmural infarction. Depending on localization of infarction, changes in the ventricular complex are observed in the corresponding leads (Figs. 83 and 84). The initial shape of ECG can be restored during cicatrization, or the changes may remain for the rest of life.

The radionuclide method can be helpful in diagnosing myocardial infarction. The patient is given pyrophosphate labelled with " Tc which is mainly concentrated in necrotized tissue, i.e. in the zone of infarction. The extent of the affection can thus be estimated.

Retrosternal oppression and general weakness are the usual symptoms

Special Part

Chapter 6. Blood Circulatory System

| |||

| |||

| |||

|

| Stage |

Ventricular complex