Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Methods of Examination 1 страница. Complaints.Patients with disorders of the hepatobiliary system usually complain of abdominal pain, dyspepsia

|

|

Inquiry

Complaints. Patients with disorders of the hepatobiliary system usually complain of abdominal pain, dyspepsia, skin itching, jaundice, enlargement of the abdomen, and fever.

Pain is localized in the right hypochondrium and sometimes in the epigastrium and differs depending on the cause. Pain may be persistent and dull, or it may be severe and occur in attacks. Persistent pain is usually boring, or the patient feels pressure, heaviness, or distension in the right hypochondrium. Pain may radiate to the right shoulder, scapula, and in the interscapular space (in chronic cholecystitis, perihepatitis and pericholecystitis, i.e. when the process extends onto the peritoneum overlying the liver and the gall bladder, and also in rapid and considerable enlargement of the liver which causes distension of Glisson's capsule). This radiation of pain is quite characteristic of many diseases of the liver and gall bladder, because the right phrenic nerve, innervating the capsule in the region of the falciform and the coronary ligaments of the liver and the ex-trahepatic bile ducts, originates in the same segments of the spinal cord where the nerves of the neck and shoulder originate as well. Pain usually becomes more severe in deep breathing; in adhesion of the liver or the gall bladder to the neighbouring organs, pain is also intensified when the patient changes his posture, and sometimes during walking.

Attacks of pain (biliary or hepatic colics) develop suddenly and soon become quite severe and unbearable. The pain is first localized in the right hypochondrium but then spreads over the entire abdomen to radiate upwards, to the right, and posteriorly. An attack of pain may continue from several hours to a few days during which pain may subside and then intensify again; the attack ends as suddenly as it arises; or pain may lessen gradually. Attacks of pain occur mostly in cholelithiasis. They are provoked by jolting (as in riding) or by fatty food. Pain attacks occur also in hypermotoric dyskinesia of the gall bladder and bile ducts. Pain usually develops quite unexpectedly due to spastic contractions of muscles of the gall bladder and large bile ducts caused by irritation of their mucosa by a stone, and due to comparatively rapid distension of the gall bladder in congestion of bile (e.g. due to obstruction of the common bile duct by a stone). Warmth applied to the liver (provided the attack is not attended by considerable fever) and also administration of cholino- and myospasmolytics

Chapter 7. Digestive System

(atropine sulphate, papaverin hydrochloride, etc.) remove pain characteristic of the colic. An attack of hepatic colic can be attended by subfebrility (fever develops with pain and subsides with alleviation of pain), which is followed by a slight transient subicteric colour of the sclera Or pronounced jaundice in obstruction of the common bile duct by a stone.

Pain developing in dyskinesia of the bile ducts is associated with upset coordination between contractions of the gall bladder and of the Oddi sphincter under the effect of increased tone of the vagus nerve. As a result, bile congests in the ducts, and the gall bladder is no longer emptied. This causes its convulsive contraction. Dyskinetic pain is characterized by the absence of signs of inflammation (leucocytosis, ESR, etc.).

Dyspeptic complaints include decreased appetite, often bitter taste in the mouth, eructation, nausea, vomiting, distension of the abdomen and rumbling, constipations or diarrhoea. These complaints are characteristic not only of diseases of the hepatobiliary system but also of other parts of the digestive system. Causes of these symptoms in diseases of the liver and bile ducts are explained by deranged secretion of bile (and hence impaired digestion of fats in the intestine) and derangement of the detoxicating function of the liver.

Fever occurs in acute inflammatory affection of the gall bladder and bile ducts, in abscess and cancer of the liver, in hepatitis, and active cirrhosis.

Skin itching attends hepatic or obstructive jaundice. It can develop without jaundice, as an early forerunner of the liver disease. Itching is caused by accumulation in the blood of bile acids which are otherwise excreted together with bile, or by stimulation of sensitive nerve endings in the skin. Itching is usually persistent and is a great annoyance to patients during night sleep (to cause insomnia). Severe itching causes scratching of the skin with its subsequent infection.

Icteric colouration of the skin and the visible mucosa (jaundice) is due to accumulation of bile pigments in the blood and tissues. Jaundice may develop unnoticeably to the patient and only the surrounding people may pay attention to the icteric colouration of the sclera and then the skin. In other cases jaundice can occur all of a sudden, following an attack of hepatic colics (in obstruction of the common bile duct by a stone in cholelithiasis). Jaundice may persist for months or even years, only slightly changing in intensity (chronic hepatitis and cirrhosis of the liver, benign bilirubinaemia). For details of the mechanism of developing jaundice and its diagnostic importance see below.

Enlargement of the abdomen (sometimes rapid) can be due to accumulation of ascitic fluid in the abdominal cavity (in obstructed blood

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

outflow from the intestine via the portal vein), in considerable meteorism (due to deranged digestion in the intestine in upset bile excretory function), or in pronounced hepato- or splenomegaly. Many chronic diseases are attended by general weakness, non-motivated fatigue, and decreased work capacity.

outflow from the intestine via the portal vein), in considerable meteorism (due to deranged digestion in the intestine in upset bile excretory function), or in pronounced hepato- or splenomegaly. Many chronic diseases are attended by general weakness, non-motivated fatigue, and decreased work capacity.

History of the present disease. When collecting anamnesis, it is necessary to find out if the patient had in his past history jaundice or acute diseases of the liver or the gall bladder (Botkin's disease, acute cholecystitis, cholangitis), attacks of hepatic colics, enlargement of the liver or the spleen, which might be an early symptom of the present disease (chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, chronic cholecystitis, cholangitis, cholelithiasis).

Life history of patient. When inquiring the patient it is necessary to establish factors that might be important for the aetiology of the present disease of the liver or bile ducts: liking for fat and meat foods, exposure to chemical and vegetable poisons (alcohol, carbon tetrachloride, compounds of phosphorus, copper, lead, arsenic, dichloroethane, etc.), poisoning with mushrooms containing strong hepatotropic poisons (e.g. helvellic acid, amanitotoxin, etc.), some infectious diseases (Botkin's disease, lambliosis, typhoid fever, malaria, syphilis, etc.), diseases of the gastro-intestinal tract (gastritis, colitis), and diabetes mellitus. Familial predisposition is also important in the development of some liver diseases (e.g. congenital benign hyperbilirubinaemia) and diseases of the gall bladder (cholelithiasis).

Physical Examination

INSPECTION

The general condition of the patient is first assessed. In the presence of marked functional hepatic insufficiency of various aetiology (liver cirrhosis, cancer, prolonged obstructive jaundice, etc.), the patients's condition can be grave because of pronounced poisoning (hepatic coma). The patient's condition may be grave in acute inflammatory diseases of the liver (abscess), gall blader (acute cholecystitis), or bile ducts (acute cholangitis). But in many chronic diseases of the liver and the bile ducts, the general condition of the patient may remain satisfactory for long periods of time. Patients with hepatic colics are restless, they toss in bed, try to find (without success) a position in which the pain might be relieved. A hepatic

coma is characterized by deranged consciousness in the form of pronounced euphoria or inhibition to complete loss of consciousness.

The general appearance (habitus) of the patient usually does not change. At the same time, a hypersthenic constitution with predisposition to obesity is often characteristic of patients with cholelithiasis. Quite the reverse, significant wasting (to cachexia) occurs in cirrhosis or malignant tumour of the liver or the bile ducts. If the disease of the liver begins in childhood or adolescence, the patient may look infantile.

An important diagnostic sign is jaundice of varying intensity. In order to assess correctly the colour of the skin, the patient should be inspected in daylight or in the light of the luminescent lamp. A subicteric symptom is jaundice of the sclera, the lower surface of the tongue, and the soft palate; next coloured are the palms, soles, and finally the entire skin. Inspection of the sclera helps differentiate between true (bilirubinogenic) and exogenic jaundice. Prolonged use of quinacrine, ethacridine lactate (rivanol), carotin (carrots), excess tangerines and oranges, exposure to trinitrotoluene and picric acid can cause slight jaundice of the skin (false jaundice) but the sclera is not coloured in such cases. Hepatic jaundice is usually attended by itching and scratching of the skin.

Icteric skin can be of various hues (Plate 18). The skin is orange-yellow (rubinicterus) due to accumulation of bilirubin in the skin; it is usually characteristic of the early stages of the disease. Lemon-yellow colour of the skin (flavinicterus) is characteristic of haemolytic jaundice. Greenish-yellow colour (verdinicterus) is due to accumulation of biliverdin (the product of gradual oxidation of bilirubin); it is mostly due to obstructive jaundice. In long-standing mechanical jaundice the skin becomes dark bronzy (melasicterus).

In certain cases the skin becomes pallid due to anaemization (haemorrhage from varicose oesophageal or haemorrhoidal veins in portal cirrhosis); the skin may be greyish (" dirty") in patients with some hepatic diseases. Greyish-brown or brown skin is characteristic of haemochromatosis (bronzed diabetes or pigmentary cirrhosis of the liver), the disease associated with primary or secondary excessive absorption of iron in the intestine and accumulation of haemosiderin in various organs and tissues (in the first instance in the liver and the pancreas). Local hyper-pigmentation of the skin in the right hypochondrium can be due to frequent application of a hot-water bottle, which indicates persistent pain in this region (in chronic diseases of the gall bladder).

Inspection of the skin (especially in obstructive and less frequently in

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

parenchymatous jaundice) can reveal scratches due to severe itching. The scratches are often infected and purulent. Jaundice of this type can be attended by haemorrhagic diathesis— petechial eruption and haemorrhage into the skin (ecchymosis).

parenchymatous jaundice) can reveal scratches due to severe itching. The scratches are often infected and purulent. Jaundice of this type can be attended by haemorrhagic diathesis— petechial eruption and haemorrhage into the skin (ecchymosis).

In patients with cirrhosis of the liver associated with disordered cholesterol metabolism, cholesterol is deposited intracutaneously in the form of yellow plaques (xanthomatosis) which are often located on the eyelids (xanthelasma) and less frequently on the hands, elbows and soles (xanthomas). Xanthomatosis occurs also in other diseases attended by cholesterol metabolic defect (atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, essential hyperlipaemia, etc.).

An important symptom for diagnosis of chronic diseases of the liver are spider angiomata (Plate 19). These are slightly elevated pulsating angiomata with fine vessels radiating from the centre. Their size varies from that of a pin head to 0.5-1 cm in diameter. The angiomata are often found on the neck, face, shoulders, hands, and the back; less frequently they are practically absent from the lower part of the body. The spider angiomata may disappear with improvement of the liver function. In addition to these angiomata, patients with chronic diseases of the liver may have specifically coloured palms and soles— liver palms; symmetrical reddening is especially characteristic in the thenar and hypothenar region. When pressed, the reddened site becomes pale but when the pressure is removed, the redness is quickly restored. The mechanism of development of the spider angiomata and liver palms is believed to be connected with the grave hepatic dysfunction of the liver during which oestrogens are destroyed incompletely and therefore act as a vasodilatory agent on the skin vessels.

Excess oestrogens in the blood are also associated with other symptoms that may be revealed on inspection. Patients with chronic diseases of the liver have a glassy crimson tongue (raspberry tongue). Uni- or bilateral enlargement of the mammary glands often occurs in men (gynaecomastia) along with defective growth of hair on the chin, chest, and the abdomen. Hair growth is decreased in the armpits and on the pubis in women. When the. hepatic condition improves, the hair growth is restored. Drum (Hip-pocratic) fingers, sometimes with white nails, occur in patients with chronic diseases of the liver. It is believed to depend on excess oestrogens and serotonin in the blood.

A greenish-brown Kayser-Fleischer ring round the outer edge of the cornea is characteristic of the Konovalov-Wilson disease (congenital disease characterized by decreased synthesis in the liver of ceruloplasmin, the copper transport protein, and its increased deposition in tissues).

Inspection of the mouth can reveal angular stomatitis (inflammation of the mucosa and skin in the mouth angles) characteristic of group B hypovitaminosis occurring amongst patients with chronic liver diseases.

Inspection of the abdomen should be done with the patient in erect or lying position. Important diagnostic symptoms can often be found during inspection of the abdomen. The abdomen can be enlarged significantly due to accumulation of free fluid (ascites). This occurs in liver cirrhosis concurrent with portal hypertension. The abdomen may be enlarged due to pronounced hepato- or splenomegaly. When the patient with ascites stands erect, his abdomen becomes pendulous due to the downward flow of fluid; in the lying position the abdomen is flattened (" frog belly"). The navel often becomes protruded in ascites when the patient stands erect. It is due to increased intra-abdominal pressure. This sign can be used to differentiate between enlargement of the abdomen in ascites (also large intra-abdominal tumours) and pronounced obesity (the navel is retracted).

Inspection of the abdomen can reveal another important symptom of portal hypertension, the presence of dilated venous network on the anterior abdominal wall (Plate 20). This network is formed by anastomoses of the portal and both vena cava systems. The superior vena cava and portal vein are anastomosed above the navel, while the portal and inferior vena cava are anastomosed below the navel; cavocaval anastomoses are located on the sides of the abdomen. Anastomoses may develop in obstructed blood flow in the inferior vena cava (thrombosis, compression, etc.). Dilated, swollen and twisted venous collaterals, found round the navel and radiating from it, form the so-called Medusa head. These symptoms are characteristic of the portal hypertension syndrome occurring in cirrhosis of the liver, thrombosis and compression of the portal vein. Establishing the direction of the blood flow in the collaterals helps determine the type of anastomosis and hence locate the vessel where the blood flow is obstructed in the system of the portal vein or the inferior vena cava. To that end a small area of the dilated venous branch is pressed between two fingers (with an attempt to empty this area from the blood). In a short lapse of time the pressure of the upper finger is released. If blood fills the vessel to the level of the other finger, the blood flows from the portal vein system to the inferior vena cava (i.e. in the downward direction). If the vessel remains empty, the blood flows upwards, i.e. from the vena cava inferior-system to the superior vena cava.

In patients with cachexia and pronounced enlargement of the liver, the right hypochondrium and epigastrium are protruded. If the abdominal wall is thin, the protruded surface is uneven and tuberous (in tumours or cysts of the liver). Only significantly enlarged gall bladder can be responsi-

Special Part

ble for protrusion of the abdomen, especially in cachectic patients (in hydrops of the gall bladder, cancer of the common bile duct, or cancer of the pancreas head which compresses the common bile duct). The left hypochondrium is protruded in cases with considerably enlarged spleen attending cirrhosis of the liver (hepatolienal syndrome).

ble for protrusion of the abdomen, especially in cachectic patients (in hydrops of the gall bladder, cancer of the common bile duct, or cancer of the pancreas head which compresses the common bile duct). The left hypochondrium is protruded in cases with considerably enlarged spleen attending cirrhosis of the liver (hepatolienal syndrome).

PERCUSSION

Percussion is used to determine the borders, size and configuration of the liver. The superior and inferior borders of the liver are outlined. Two superior borders of liver dullness are distinguished: relative dullness, which is the true upper border of the liver, and the absolute dullness, i.e. the upper border of that part of the anterior surface of the liver which is directly adjacent to the chest and is not covered by the lungs. Practically, absolute dullness is only determined because the position of the superior border varies depending on the size and configuration of the chest, the height of the right diaphragm cupola, and also because the upper edge of the liver is deeply hidden behind the lungs. Finally, the liver usually becomes enlarged in the downward direction. This is determined by the position of its inferior edge.

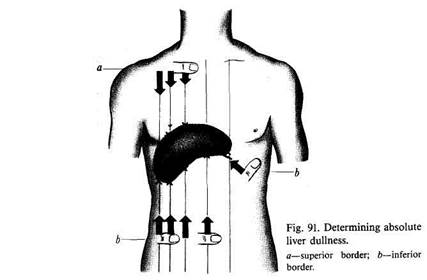

Percussion of the liver is carried out with observation of the general rules of topographic percussion. Light percussion is used to determine the absolute liver dullness. The direction of percussion is from top to bottom, along the vertical lines, like in determining the borders of the right lung. The border is detected by contrast between the clear pulmonary resonance and liver dullness. The found border is marked on the skin by dots, by the upper edge of the pleximeter-finger, in each vertical line. Normally the superior border of absolute liver dullness is found in the right parasternal line at the superior edge of the 6th rib, in the right midclavicular line at the 6th rib, and in the right anterior axillary line at the 7th rib. In other words, the border of absolute dullness corresponds to the position of the lower edge of the right lung (Fig. 91). The upper border of the liver can likewise be determined posteriorly, but normally the determination ends by percussion in the three mentioned lines.

Determination of the lower absolute dullness is difficult because of the presence of hollow organs in the vicinity of the liver. The stomach and the intestine give high tympany that masks the liver dullness. The lightest percussion should therefore be used. Direct percussion by one finger according to Obraztsov should better be used instead.

Determination of the lower border of absolute dullness (according to Obraztsov and Strazhesko) should be begun from the right part of the ab-

domen along the right anterior axillary line with the patient in the horizontal position. The pleximeter-finger is placed parallel to the expected inferior border of the liver, some distance away from it, so that tympany might first be heard (at the umbilical level or slightly below the navel). As the pleximeter-finger is then moved upwards, tympany is followed by absolute dullness. The point of disappearance of tympany is marked in each vertical line (right midclavicular, right parasternal, and anterior median line). If enlargement of the liver is significant, the mark should be made also in the left parasternal line, by the lower edge of the pleximeter-finger.

When determining the left border of liver dullness, the pleximeter-finger is placed perpendicularly to the edge of the left costal arch, at the level of the 8-9th ribs, and percussion is carried out to the right, directly over the edge of the costal arch, to the point where tympany changes to dullness (in the region of Traube's space).

Normally the inferior border of absolute dullness of a lying patient with normosthenic chest passes at the 10th rib in the right anterior axillary line, at the superior edge of the right arch in the midclavicular line, 2 cm below the interior edge of the right costal arch in the right parasternal line, and 3-6 cm away from the inferior edge of the xiphoid process (at the border of the upper third of the distance from the base of the xiphoid process to the navel) in the anterior median line; on the left the border does not extend beyond the left parasternal line.

The lower margin of the liver in norm can very depending on the shape of the chest and constitution of the patient, but this only has its effect on

27-1556

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

the position in the anterior median line. The lower margin of the liver in a hypersthenic chest is slightly above the mentioned level, while in an asthenic chest below it, approximately midway between the base of the xiphoid process and the navel. If the patient is in the upright posture, the lower margin of the liver descends 1—1.5 cm. If the liver is enlarged, its lower margin is measured in centimetres from the costal arch and the xiphoid process. The border of the left lobe of the liver is determined in centimetres in the left parasternal line, down to the margin of the costal arch and to the left in this line (by the course of the costal arch).

the position in the anterior median line. The lower margin of the liver in a hypersthenic chest is slightly above the mentioned level, while in an asthenic chest below it, approximately midway between the base of the xiphoid process and the navel. If the patient is in the upright posture, the lower margin of the liver descends 1—1.5 cm. If the liver is enlarged, its lower margin is measured in centimetres from the costal arch and the xiphoid process. The border of the left lobe of the liver is determined in centimetres in the left parasternal line, down to the margin of the costal arch and to the left in this line (by the course of the costal arch).

Percussion gives information about the vertical dimensions of the area of liver dullness. The distance between the superior and inferior borders of absolute dullness is measured in the vertical lines. This distance in the right anterior axillary line is normally 10-12 cm, in the right midclavicular line 9—11 cm, and in the left parasternal line 8—11 cm. It is difficult to determine liver dullness on the back because it is masked by dullness of the thick layer of lumbar muscles, the kidneys, and the pancreas. In some cases, a 4-6 cm wide band of liver dullness can be determined. This precludes erroneous diagnosis of liver enlargement in cases where the liver descends below the right costal arch, or where it is turned anteriorly round its axis; dullness then becomes narrower.

Outlining the liver by percussion is diagnostically important. But ascending or descending of the superior margin of the liver is usually associated with extrahepatic changes (high or low diaphragm, sub-diaphragmal abscess, pneumothorax, or pleurisy with effusion). The superior margin of the liver can ascend only in echynococcosis or cancer of the liver..Elevation of the inferior margin indicates diminution of the liver; it can also occur in meteorism and ascites which displace the liver upwards. The lower border usually descends when the liver is enlarged (due to hepatitis, cirrhosis, cancer, echynococcosis, blood congestion associated with heart failure, etc.). But it can sometimes be explained by low position of the diaphragm. Systematic observation of the liver borders and changes in the liver dullness gives information on changes in its size during the disease.

The gall bladder cannot as a rule be determined by percussion. But if its enlargement is pronounced, it can be determined by very light percussion.

Percussion is used not only to determine the borders of the liver and the

gall bladder (topographic percussion) but also to assess their condition:

careful percussion of the area overlying an enlarged liver or the gall bladder

causes painful sensations in the presence of inflammation (hepatitis,

cholecystitis, pericholecystitis, etc.). Succussion on the right costal arch

also causes pain in diseases of the liver and the bile ducts, especially in

cholelithiasis (Ortner's symptom).

PALPATION

Surface palpation in diseases of the liver can reveal a tender zone in the right hypochondrium and epigastrium. Especially severe local pain (caused even by a slight touch on the anterior abdominal wall in the zone overlying the gall bladder) is observed in acute cholecystitis and biliary colic. In chronic cholecystitis slight or moderate tenderness is only revealed at the point of projection of the gall bladder fundus onto the anterior abdominal wall. In healthy subjects this point is found immediately below the right costal arch by the lateral edge of the right rectus abdominis muscle.

The liver is palpated by the Obraztsov and Strazhesko method. As the lower edge of the liver descends to meet the examining fingers during a deep inspiration it slides over the fingers and thus becomes detectable. It should be remembered that the respiratory mobility of the liver is the highest compared with that of the other abdominal organs because the liver is the closest to the diaphragm. It follows therefore that during palpation of the liver, the active role belongs to its respiratory mobility rather than to the palpating fingers (as is the case with palpation of the intestine).

The patient should stand or lie during palpation of the liver and the gall bladder. But in certain cases the liver can be easier palpated if the patient lies on his left side: the liver hangs by gravity from under the hypochondrium and its inferio-anterior edge can thus be better palpated. Common rules should be followed during palpation of the liver and the gall bladder. Special attention should be paid to the antero-inferior margin of the liver whose properties (outlines, form, tenderness, consistency) are indicative of the condition of the liver, its position, and configuration. In many cases (especially if the liver is enlarged or lowered) the liver can be palpated not only from the left hypochondrium to the right hypochondrium, but its superio-anterior surface becomes palpable as well.

The examiner sits by the right side, facing the patient. He places four fingers of his left hand on the right lumbar region of the patient and uses his left thumb to press on the costal arch to move the liver closer to the palpating fingers of the right hand and to prevent expansion of the chest during inspiration. This stimulates greater excursions of the right cupola of the diaphragm. The palm of the right hand is placed flat on the abdomen below the costal arch in the midclavicular line. The slightly flexed fingers press lightly on the abdominal wall (Fig. 92). The patient is asked to take a deep breath; the liver descends to touch the palpating fingers and then slides to bypass them (Fig. 93). The examiner's hand remains motionless. The procedure is repeated several times. The position of the liver margin varies depending on conditions. It is therefore necessary first to determine the lower margin of the liver by percussion before positioning the palpating fingers.

27*

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

1 Fig. 92. Palpation of the liver.

According to Obraztsov, normal liver can be palpated in 88 per cent of cases. Physical properties of the liver can be determined by palpating its lower edge (it can be soft, firm, rough, sharp, rounded, tender, etc) The margin of an unaffected liver palpated at the height of a deep inspiration is 1-2 cm below the costal arch. It is soft, sharp, readily bending, and insensitive.

|

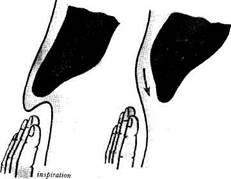

| Fig. 93. Palpation of the liver (diagram). |

| expiration |

The lower edge of a normal liver is usually palpated in the right midclavicular line; the liver is impalpable to the right of this line because it

is located behind the costal arch; the liver is hardly palpable to the left of the line because of the abdominal muscles. An enlarged or consolidated liver can be palpated in all lines. The liver of patients with pronounced distension of the abdomen should be examined with the empty stomach to facilitate palpation. In accumulation of much fluid in the abdominal cavity (ascites) the liver is not always palpable if the patient is lying. The patient should then be examined in the erect position, or he may lie on his left side. If the amount of fluid in the abdomen is very large, it should be released by paracentesis.