Главная страница Случайная страница

КАТЕГОРИИ:

АвтомобилиАстрономияБиологияГеографияДом и садДругие языкиДругоеИнформатикаИсторияКультураЛитератураЛогикаМатематикаМедицинаМеталлургияМеханикаОбразованиеОхрана трудаПедагогикаПолитикаПравоПсихологияРелигияРиторикаСоциологияСпортСтроительствоТехнологияТуризмФизикаФилософияФинансыХимияЧерчениеЭкологияЭкономикаЭлектроника

Special Pathology

|

|

The most common affection of the liver is its inflammation. Acute and chronic hepatitis, and also cirrhosis and hepatosis are distinguished. Primary cancer of the liver occurs in rare cases; as a rule malignant tumours metastasize into the liver from other organs. Echinococcus usually localizes in the liver. The liver is also affected in opisthorchiasis and some other parasitary invasions.

Affections of the bile secretion system are quite common. These are cholelithiasis, acute and chronic cholecystitis, cholangitis, dyskinesia of the bile ducts, and primary cancer of the gall bladder.

| Chronic hepatitis* is a chronic diffuse or focal inflammatory affection of the liver. |

Chronic Hepatitis: hronic diffuse or fc

| * Acute hepatitis (virus and toxic) is described in detail in special courses dealing with i fectious diseases and occupational pathology. |

Aetiology. The following groups of chronic hepatitides are distinguish-

ed: (1) infectious and parasitogenic; infectious hepatitis develops secondary to virus hepatitis, brucellosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, and some other diseases; (2) toxic hepatitis caused by industrial, medicamentous, domestic and food chronic poisoning by hepatotropic toxic substances (chloroform, trinitrotoluene, aminazine, lead compounds, etc); (3) toxico-allergic hepatitis, which develops not only in response to direct toxic effect of some medicines or hepatotropic chemicals, but also due to hypersensitivity of the liver cells of the entire body to these substances (medicamentous hepatitis, hepatitis associated with collagenosis); (4) metabolic hepatitis, which arises due to metabolic disorders in the liver, associated with protein-vitamin deficiency, and also in fat dystrophy and amyloidosis.

In 40—70 per cent of cases chronic hepatitis develops as an outcome of an acute epidemic or serum hepatitis. Hepatitides are mostly diffuse affections of the liver. Liver affections are focal in tuberculosis (tuberculous granulomas, caseous abscesses or tuberculoma), syphilis (gumma), some protozoal disease (amoebic abscesses), fungal and bacterial affections (usually abscesses), and in some other cases.

Pathogenesis. This is mostly determined by the aetiology of the disease. When exposed chronically to hepatotropic toxic substances, the hepatocytes become progressively affected (to necrobiosis); the secondary inflammatory reaction of the liver mesenchyma is equally important in the pathogenesis of chronic hepatitis. Hepatitis of virus nature is probably associated with persistence of the virus in the liver cells and with the progressive cytopathic effect of this virus, which kills the hepatocytes to cause inflammatory reaction of the connective tissue. In many cases autoimmune processes are of primary importance. They arise in response to the primary affection of the liver tissue by any aetiological factor. Obstructed bile excretion and bile congestion, cholangitis and choiangiolitis (with subsequent extension of inflammation onto the liver tissue), and also some medicamentous poisonings (phenothiazine derivatives) are decisive in the pathogenesis of the so-called cholestatic hepatitis.

Pathological anatomy. Among diffuse inflammatory affections of the liver benign (non-active, persisting), aggressive (recurrent, active), and cholestatic chronic hepatitis are distinguished.

Non-active hepatitis is characterized by inflammation in the periportal zones, preservation of the lobular structure, and sometimes by moderate dystrophic changes in the hepatocytes. The liver is enlarged, the capsule is thickened, and streaks of connective tissue are seen on its surface. The inflammatory and cicatricial processes are more distinct in the liver affected by active hepatitis. Inflammatory infiltration extends from the periportal zones inside the liver lobules whose outlines are indistinct. Hepatocytes are extensively necrotized and have dystrophic changes; fibrosis is found in the liver. The size of the liver increases, its surfaces are coarse and necrotized zones can be seen as red amorphous spots. Cholestatic hepatitis is also characterized by marked affection of bile ducts (cholangitis and choiangiolitis) and signs of cholestasis.

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

•I.

i

Hepatocellular hepatitis (epithelial and parenchymatous) and mainly mesenchymal hepatitis are also differentiated.

Clinical picture. Chronic hepatitides are characterized by (1) dyspeptic symptoms; (2) jaundice (it may be absent in some cases); (3) moderate enlargement and induration of the liver and the spleen; (4) dysfunction of the liver as determined by laboratory tests and radiohepatography. But the clinical picture and also the course of each clinico-morphological form of hepatitis have their special features.

Chronic benign hepatitis is characterized by obliterated clinical picture. The patients complain of heaviness or dull pain in the right hypochon-drium, decreased appetite, bitter taste in the mouth, nausea and eructation. Jaundice is usually absent or it is moderate. Objective studies reveal a mildly enlarged liver with a smooth surface and a moderately firm edge, which is slightly tender to palpation. Enlargement of the spleen is not marked.

Laboratory studies. The blood bilirubin content is usually normal; in the presence of jaundice it increases to about 17-50 /xmol/1 (1-3 mg/100 ml); the blood globulin content is mildly increased, activity of the enzymes is either normal or only slightly changed; the prothrombin content is normal or slightly decreased; the bromsulphthalein test is slightly positive.

Chronic active (aggressive) hepatitis is characterized by complaints and objective symptoms: weakness, loss of weight, fever, pain in the right hypochondrium, loss of appetite, nausea, regurgitation, meteorism, skin itching, jaundice, and frequent nasal bleeding. The liver is enlarged, firm, with a sharp edge. The spleen is enlarged.

Laboratory tests often reveal anaemia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia (a sign of hypersplenism), and increased ESR. Functional tests are changed considerably: they show hyperbilirubinaemia, hyperproteinaemia, hypergammaglobulinaemia, positive protein-sedimentation tests, increased activity of transaminase, aldolase, and alkaline phosphotase; decreased activity of cholinesterase. The serum iron content is significantly increased while the prothrombin index is sharply decreased; excretion of bromsulphthalein is delayed.

Puncture biopsy of the liver and (for special indications) laparoscopy establish the special histological and macroscopic changes in the liver characteristic of these forms. These techniques are also used for differentiation of chronic hepatitis from other diseases of the liver (cirrhosis, amyloidosis, etc). It should be noted that histological and histochemical studies of liver bioptates often reveal early morphological changes in the liver which precede the clinical and laboratory signs of chronic hepatitis.

Chronic cholestatic hepatitis is mainly characterized by the cholestatic syndrome: jaundice (subhepatic), severe skin itching, hyperbilirubinaemia,

increased activity of alkaline phosphatase in the blood, and high cholesterol of blood. Persistent subfebrile temperature and regular increase in ESR are also not infrequent.

Course. A benign persistent chronic hepatitis can last to 20 years; exacerbations are rare and arise only in the presence of strong provoking factors. Liver cirrhosis develops in rare cases. Complete clinical recovery is sometimes possible, especially so if the patient is specifically treated. The morphological structure of the liver is restored in such cases.

Aggressive hepatitis is characterized by relapses, whose frequency depends on various factors. Frequent relapses accelerate progressive dystrophic, inflammatory and cicatricial changes in the liver and stimulate development of cirrhosis. Prognosis in this form of hepatitis is bad.

The course and prognosis in cholestatic hepatitis depend on its aetiology and the possibility of removing the obstacle to bile outflow (in compression of the common bile duct by a tumour, cicatricial or inflammatory stenosis, etc.).

Treatment. The cause of chronic hepatitis should be removed in the first instance: complete discontinuation of taking alcohol or exposure to harmful substances, etc.

During exacerbations, the liver should be spared as much as possible, and regeneration of liver cells stimulated (bed rest, diet, parenteral use of vitamins, glucose, etc).

Cirrhosis of the Liver

Cirrhosis of the liver is a chronic progressive disease characterized by increasing hepatic insufficiency in connection with dystrophy of the liver cells, cicatricial cirrhosis, and structural reconstruction of the liver.

Aetiology. Cirrhosis of the liver is a polyaetiological disease. It may develop due to (1) infection (virus of epidemic hepatitis); (2) alcoholism; (3) protein- and vitamin-deficient diet; (4) toxico-allergic factor; (5) cholestasis. Of the mentioned aetiological factors, the leading role in this country belongs to the virus of epidemic hepatitis. Cirrhosis caused by the virus is probably explained by its long persistence in the liver cells.

Chronic alcoholic poisoning is also a very important aetiological factor. It affects absorption of vitamins and proteins in the intestine to provoke cirrhosis of the liver. It also acts directly and specifically on metabolism of the liver cells. The alimentary factor (malnutrition, mainly protein- and vitamin deficit) is a frequent cause of liver cirrhosis in some developing countries. In this country the alimentary factor (malnutrition) is only of endogenous origin: deranged absorption of proteins and vitamins (in grave chronic diseases of the gastro-intestinal tract, in patients with total resec-

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

tion of the stomach, resection of the intestine, chronic pancreatitis, and in some other cases). Toxic cirrhosis of the liver arises in repeated and chronic exposure to carbon tetrachloride, compounds of phosphorus or arsenic, in food poisoning (inedible mushrooms, seeds of heliotrope). Toxico-allergic cirrhosis of the liver includes also affections connected with hypersensitivi-ty (autoallergy) to various drugs (aminazine, chloroform, some antibiotics, sulpha preparations, etc); hypersensitivity can cause dystrophy and necrosis of the liver parenchyma.

Obturation of intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts and their inflammation cause congestion of bile and cholestasis, and are important factors in the development of biliary cirrhosis.

The aetiological factor does not always determine the way of development of liver cirrhosis. One and the same factor can cause various morphological variants of cirrhosis (portal, postnecrotic, and biliary); at the same time various aetiological factors can cause similar morphological changes.

Pathogenesis. The pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis is closely connected with morphogenesis. The greatest importance in the developmental mechanism of liver cirrhosis belongs to recurrent necrosis of the liver cells which is provoked by aetiological factors and cause collapse of the reticulin framework of the liver, formation of cicatrices, and derangement of circulation in the adjacent portions of the preserved liver parenchyma. Intact hepatocytes or lobe fragments begin their intense regeneration under the effect of growth stimulants supplied from the necrotic focus. The formed large nodes of regenerated tissue compress the surrounding tissue with the invested vessels; the hepatic veins are compressed especially strongly. The blood outflow becomes upset to provoke portal hypertension and formation of anastomoses between the branches of the portal and hepatic veins that facilitate intrahepatic circulation. Blood now bypasses the liver parenchyma to impair drastically its blood supply, to cause new ischaemic necroses, and to stimulate the progress of cirrhosis even in the absence of the primary aetiological factor. Collagenous connective tissue grows intensively: connective tissue partitions (septa) grow into the parenchyma from the periportal fields to cause fragmentation of the liver lobules. These false lobules can later become the source of nodular regeneration. Chronic direct exposure to certain toxic hepatotropic substances, and also autoimmune and some other mechanisms are important in the pathogenesis of certain forms of cirrhosis.

Pathological anatomy. Three main morphological variants of liver cirrhosis are distinguished: portal (septal), postnecrotic, and biliary.

Portal (septal) cirrhosis of the liver is usually the result of alimentary insufficiency and alcoholism; less frequently it is secondary to Botkin's disease (virus hepatitis). Its develop-

ment is underlain by formation of connective-tissue septa interconnecting periportal fields with the central zone of the lobule and causing its fragmentation. Macroscopically the liver may be enlarged or diminished. Small nodes of regenerated tissue, circumscribed by narrow septa of connective tissue, are distributed uniformly over the entire surface of the liver. The nodes are almost equal in size. The microscopic picture: marked fatty infiltration of the liver cells is observed in alimentary or alcoholic cirrhosis; these changes may be absent in cirrhosis that develops after virus hepatitis. " False bile ductules", leucocyte infiltration, and compressed small veins are found in the stroma between the nodes of regenerated tissue.

Postnecrotic cirrhosis of the liver develops as a result of submassive and massive necrosis of the liver cells due to virus and (less frequently) toxic hepatitis. Macroscopic picture is characterized by irregular changes in the liver, which is usually diminished in size. Nodes of various form and size can be seen on the liver surface. Microscopy shows irregular nodes of regenerated tissue and intact portions of the parenchyma. Broad fields of collapsed col-lagenized stroma with closely running portal tracts, venules, and cell infiltrates can be found between the nodes of the regenerated tissue. Inflammatory infiltration is marked.

Biliary cirrhosis of the liver has two variants. Primary biliary cirrhosis (pericholangiolitic) arises after epidemic hepatitis or toxico-allergic action of some medicinal preparations. Its development is underlain by obstruction of fine intrahepatic bile ductules which accounts for bile congestion. Macroscopy: the liver is enlarged and consolidated and is dark-green or olive in colour; it is microgranular. Extrahepatic bile ducts are patent. Microscopy is characterized by the presence of intralobular and periportal cholestases. The periportal fields are broad, with fibrosis around proliferating cholangioles; intralobular fibrosis develops around intralobular cholangioles with dissociation of the liver cells and their groups. Secondary biliary cirrhosis arises as a result of prolonged obstruction of extrahepatic bile ducts by stones, tumour, etc. It provokes dilation of the bile ducts, development of cholangitis, and pericholangitis; cirrhosis of the liver develops if these changes progress.

In addition to the described variants of cirrhosis, they may also be mixed: morphological signs of other variants may join the main variant. Activity of cirrhosis is characterized by the presence of new dystrophic and regenerative processes in the parenchyma, intense inflammatory infiltrations in the stroma, proliferation of cholangioles, indistinct borders between nodular parenchyma and internodular stroma. A neglected cirrhotic process is characterized by replacement of liver tissue by nodes of regenerated tissue, markedly pronounced portal hypertension, large quantity of vascular connective-tissue septa growing into the parenchyma (portohepatic anastomoses). According to the morphological picture, fine- and large-nodular cirrhosis is distinguished. Mixed variants also occur.

Clinical picture. Portal cirrhosis of the liver occurs mostly between the ages of 40 and 60. The incidence in men is twice higher than in women. Postnecrotic and biliary cirrhosis of the liver develop in younger patients, mostly in women.

Clinical manifestations of liver cirrhosis depend on the degree of affection of the liver cells and the associated hepatic dysfunction and portal hypertension, on the stage of the disease (compensated or decompensated), and also on the activity of the process. The following symptoms of the disease are most characteristic of the majority of patients with various forms of liver cirrhosis.

Pain in the region of the liver, in the epigastrium, or diffuse pain in the whole abdomen is usually dull and boring, intensifying after meals,

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

especially after fatty food, ample drinking and physical exercise. Pain is usually associated with enlargement of the liver and distension of the capsule, or with necrotic foci located near the capsule, with perihepatic symptoms, and also concurrent inflammatory affections of the bile ducts.

especially after fatty food, ample drinking and physical exercise. Pain is usually associated with enlargement of the liver and distension of the capsule, or with necrotic foci located near the capsule, with perihepatic symptoms, and also concurrent inflammatory affections of the bile ducts.

Dyspepsia in the form of decreased appetite to complete anorexia, the feeling of heaviness in the epigastrium after meals, nausea, vomiting, meteorism and dyspeptic stools (especially after fatty meals) depend mainly on deranged secretion of bile and hence defective digestion. But they can also be associated with the attending dyskinesia of the bile ducts or alcoholic gastroenteritis.

Decreased work capacity, general weakness, fatigue and insomnia are often observed in cirrhosis of the liver. Fever is usually irregular and sometimes of the undulant type. It often attends postnecrotic cirrhosis of the liver and is explained by necrotic destruction of the liver cells. Marked fever is characteristic of the active period and infectious cirrhosis.

A haemorrhagic syndrome is observed in 50 per cent of patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Profuse bleeding from varicose veins of the oesophagus and the stomach can often be early signs of portal cirrhosis; they are caused by increased pressure in the veins of the oesophagus and the stomach. In other variants of cirrhosis nasal, gum, uterine and skin haemorrhages develop in marked decompensation. They depend on the decreased coagulability of blood due to liver dysfunction.

Signs of cirrhosis are as follows. Cachexia is especially characteristic of patients with portal cirrhosis of the liver. In long-standing disease the subcutaneous fat disappears along with atrophy of muscles, especially of the upper shoulder girdle. The appearance of such patients is quite specific: the face is very thin with grey or subicteric skin; the lips and the tongue are bright-red; the cheek bone region is affected by erythema; the extremities are thin and the abdomen is large (due to ascites, enlarged liver and spleen); the subcutaneous veins of the abdominal wall are dilated, the legs are oedematous. Malnutrition is usually associated with disordered digestion and assimilation of food, and impaired synthesis of proteins in the affected liver.

Jaundice (except the cases with biliary cirrhosis) is a sign of hepatocellular insufficiency associated with necrosis of the liver cells. The affected hepatocytes partly lose their capacity to capture bilirubin from blood and to bind it with glucuronic acid. Bilirubin excretion into bile is disordered as well. Free (indirect) and bound (direct) bilirubin of blood serum therefore also increases. Jaundice is usually characterized by partial decolouration of faeces and by the presence of bile in the duodenal contents. Jaundice is often attended by skin itching. Jaundice associated with biliary cirrhosis resembles obstructive jaundice; severe skin itching is

observed. The intensity of jaundice varies from light subicteric to marked jaundice (depending on the degree of obstruction of the bile ducts). In prolonged obstruction of the extrahepatic duct the skin acquires a greenish tint which depends on oxidation of bilirubin to biliverdin. Moreover, brown pigmentation of the skin may also be observed. It depends on accumulation of melanin.

" Minor" signs of cirrhosis can also be revealed during examination of the patient. These signs are as follows: (1) spider angiomata (they may develop years before marked symptoms of the disease develop); their number increases and the colour intensifies during exacerbation of the disease; (2) erythema of the palms; (3) red lustrous lips, scarlet mucosa of the mouth, scarlet (lacquered) tongue; (4) gynaecomastia (increased mammary glands) and other female sex characters developing in men (decreasing growth of hair on the face, chest, abdomen, and the head); (5) xan-thomatous plaques on the skin (observed in patients with biliary cirrhosis of the liver); (6) Hippocrates fingers with hyperaemic skin at the nail beds. Inspection of the abdominal skin can reveal dilation of the veins that can be seen through the thinned skin of the abdominal wall (caput medusae). Collateral venous system can be seen on the chest as well. Haemorrhoidal veins are often dilated.

Ascites is the most characteristic sign of portal cirrhosis. Ascites may develop slowly and the abdomen grow to huge size; the patient develops dyspnoea. Oedema may develop; hydrothorax may also occur in some cases. In other variants of cirrhosis, ascites develops at later stages of the disease.

Enlarged liver can be palpated in 50-75 per cent of patients with cirrhosis. The enlargement can be insignificant, only determinable by percussion, or considerable when the liver occupies the entire left part of the abdominal cavity. The liver is firm, the surface is sometimes irregular, and the lower edge sharp. Enlargement of the spleen is often attended by its increased activity (hypersplenism).

Laboratory findings. An active cirrhotic process is characterized by anaemia, leucopenia, thrombocytopenia, and increased ESR. Anaemia can be due to hypersplenism and gastro-intestinal haemorrhage, hepatocellular insufficiency, and often increased haemolysis, which is accompanied by reticulocytosis of the peripheral blood.

The blood serum bilirubin content becomes considerable only in the final stage of the disease. At the same time, the affection of the excretory function of the cirrhotic liver can be assessed by the presence of the conjugated fraction of bilirubin (bound bilirubin). Its content increases in normal and increased total bilirubin. The free bilirubin content increases in the blood serum as a result of upset conjugation of bilirubin in the liver cell

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

and haemolysis. The blood serum bilirubin content varies in biliary cirrhosis of the liver from 26 to 340 /*mol/l (1.5-20 mg/100 ml), mostly at the expense of bound bilirubin.

and haemolysis. The blood serum bilirubin content varies in biliary cirrhosis of the liver from 26 to 340 /*mol/l (1.5-20 mg/100 ml), mostly at the expense of bound bilirubin.

The presence of much urobilin in the urine indicates liver insufficiency. The amount of urobilin in the urine and stercobilin in the faeces decreases in the presence of pronounced jaundice when a small amount of bilirubin enters the intestine. Bilirubin is found in the urine of patients with jaundice.

The upset excretory function of the liver is manifested by retention of bromsulphthalein in the blood (during its intravenous administration) and also by radioisotopic hepatography and scanning of the liver.

Affection of liver cells is manifested by characteristic changes in the protein indices: decreased concentration of serum albumins and hypergam-maglobulinaemia which in turn decreases the albumin-globulin coefficient. Activation of the inflammatory process in the liver involves an increase in the a2-globulins, while jaundice causes an increase in 0-globulins. During remissions, all these changes become less pronounced. The blood level of lipids and cholesterol also increases considerably in the presence of biliary cirrhosis. A sensitive index of liver dysfunction is the decreased activity of cholinesterase. Transaminase activity increases in exacerbation of liver cirrhosis. Activity of alkaline phosphatase also increases in biliary cirrhosis.

The decreased prothrombin content (which is synthesized by the liver cells), increased antithrombin coagulative activity and decreased total coagulative activity of plasma are important in the aetiology of haemor-rhagic diathesis in liver cirrhosis.

Laparoscopy and especially biopsy of the liver help reveal intravital morphological signs of each variant of liver cirrhosis. Varicose veins of the oesophagus are revealed by X-rays.

It is not always possible to differentiate between all variants of liver cirrhosis from the data of clinical and instrumental methods of examination, nevertheless, by comparing the mentioned signs, one can notice that the symptoms of portal hypertension in portal cirrhosis of the liver are often revealed long before the functional insufficiency develops. Hepatic insufficiency only develops at a later stage of the disease. But in the presence of postnecrotic cirrhosis of the liver, the symptoms of hepatic insufficiency develop early. They largely determine the entire clinical picture of the disease. Chronic jaundice (obstructive type) prevails in the clinical picture of biliary cirrhosis along with satisfactory general condition of the patient, who suffers from skin itching, sometimes fever (associated with chills); the blood alkaline phosphatase and cholesterol content increases. Transcutaneous cholangiography is used to determine the cause of cholestasis. The procedure is done when indicated.

Complaints of patients with compensated liver cirrhosis are not serious. The disease is often revealed accidentally during examination (enlarged liver and spleen). Remissions may be long (measured by years). Decompen-sated active cirrhosis is characterized by marked symptoms of the disease and rapid progressive course.

Course. The course of the disease is usually progressive. The overall term of the disease is usually 3 to 5 years; in rare cases the disease may last 10 years and even longer (usually in biliary cirrhosis of the liver).

The terminal period of the disease, irrespective of the form of cirrhosis, is characterized by gastro-intestinal haemorrhage and progressive signs of functional insufficiency of the liver, with finally developing coma. These are two most frequent direct causes of death of patients with liver cirrhosis. Gastro-intestinal haemorrhage (blood vomiting and melaena) is caused by the rupture of varicose nodes in the lower third of the oesophagus or, less frequently, in the stomach. A direct cause of varicose haemorrhage is physical strain or local affection of the mucosa (e.g. by coarse food). Profuse haemorrhage (if it does not cause death) can cause anaemia with subsequent impairment of the function of the liver cells and accelerated development of hepatic coma.

Treatment. Cirrhosis of the liver in the compensation stage is treated by preventing its further affection with alcohol, toxic substances, etc., and also by rational organization of work regimen and nutrition (high-calorie diet rich in protein and vitamins). During decompensation stage, hospital treatment is required. Glucocorticosteroid hormones are given in the active process (except cases complicated by dilation of the oesophageal veins); syrepar (hydrolysate of cattle liver), essential (a complex preparation containing essential phospholipids), and vitamins are also prescribed. Patients with ascites are prescribed a diet restricted in salt and diuretics (periodically). If ascites cannot be cured by diuretics, the fluid is released by paracentesis.

In order to decrease the lipid content of the serum in primary biliary cirrhosis, lipoic acid preparations are prescribed. Skin itching is removed by cholestyramine (preparation binding fatty acids). Surgical treatment is indicated in cases with secondary biliary cirrhosis of the liver, e.g. in obstruction of the bile duct by a stone.

Cholelithiasis

Cholelithiasis is characterized by formation of stones in the gall bladder or, less frequently, in the bile ducts. The incidence of the disease is rather high. According to the data of postmortem examination, stones are found in the gall bladder of every tenth patient who dies from various causes. At

R

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

the same time, clinical signs of cholelithiasis are only found in 10 per cent of carriers of stones, mainly in women aged 30—55.

the same time, clinical signs of cholelithiasis are only found in 10 per cent of carriers of stones, mainly in women aged 30—55.

Aetiology and pathogenesis. The disease is underlain by general metabolic disorders which provoke formation of stones. Infection and bile congestion are also important. Upset cholesterol metabolism with hyper-cholesterolaemia attended by the increased bile cholesterol content is decisive because most stones contain cholesterol. This is also confirmed by the fact that cholelithiasis often concurs with atherosclerosis, diabetes mellitus, obesity, and other conditions attended by hypercholesterolaemia. Frequent formation of pigmented stones in the presence of excess bilirubin in bile in haemolytic anaemia (haemolytic jaundice) is explained in a similar way. At the same time, blood cholesterol is not increased in all patients with cholelithiasis. There is no parallelism between cholesterol level of bile and blood.

The main components of stones are cholesterol, bilirubin, and calcium. These are contained in bile in the form of unstable colloidal solutions. Cholesterol is retained in bile mainly by bile acids. When cholate level in the bile decreases, cholesterol precipitates as crystals. The ratio between salts of bile acids (cholates) and cholesterol in normal bile is 15: 1; in cholelithiasis this ratio decreases to 6: 1. Disorders in the physico-chemical composition of bile are believed to be decisive for stone formation. Hepatocyte dysfunction decreases the formation of bile acids which may be the cause of dyscholia.

The importance of the infectious factor consists in that protein-rich ex-udate of inflamed gall bladder upsets the normal colloidal and chemical composition of bile to precipitate bilirubin, cholesterol and calcium, and to cause formation of mixed stones typical for infectious diseases of the gall bladder.

Bile congestion in the gall bladder provides conditions for stone formation because it promotes concentration of bile and stimulates an increase (10—12 times) in cholesterol concentration in the bile, while gradual absorption of bile acids decreases their content in the bile. Moreover, bile congestion can provide favourable conditions for development of infection. Disordered neurohumoral regulation of contractility of the gall bladder and bile ducts (dyskinesia), as well as the anatomical changes in the bile passages (bends, adhesions, scars), are essential factors provoking bile congestion. Factors interfering with normal emptying of the gall bladder are also important: increased intra-abdominal pressure (e.g. during pregnancy), ptosis of the internal organs, persistent constipations, hypodynamia, and rare meals are among these factors.

Hereditary predisposition is also very important. Stones often occur in several generations of one family (especially among women). Excessive

food rich in fats and calories causes hypercholesterolaemia and stimulates formation of gall stones.

Pathological anatomy. There exist three major groups of gall stones. Purely cholesterol stones are white or yellowish concretions which are found in the gall bladder. They usually develop as single round or oval concretions. The stones are light (float on the surface of water) and burn with a bright flame. The section of a stone shows its radial structure (crystals of cholesterol). Pigment stones consist of bilirubin and calcium. Their shapes vary. Usually pigment stones are small and multiple. Their colour is black with a greenish tint; the stones are dense but brittle. Stones consisting of only calcium carbonate rarely occur. Mixed stones consisting of cholesterol, calcium, and pigment occur most frequently. They are heavier than water and burn with difficulty. A section reveals laminar structure. The shape and size of mixed stones vary but they are usually small and multiple. If stones are tightly packed in the gall bladder, their surfaces become facetted (from mutual pressure).

The mucosa of the gall bladder can be affected with inflammation in the presence of stones (see " Cholecystitis"). Prolonged presence of stones in a non-inflamed gall bladder can cause atrophy and sclerosis of the bladder wall or (in very rare cases) decubitus and perforation of its walls.

Clinical picture. Pain attacks in the right hypochondrium (the so-called biliary colic) are the most characteristic symptom of cholelithiasis. Colics are usually provoked by small stones as they move in the region of the neck of the gall bladder, its isthmus, or directly in the cystic duct. Pain is caused by spastic contractions of the gall bladder and the ducts which develop as a result of a sudden distension of the gall bladder and increased pressure inside it due to a mechanical obstruction to bile outflow. The pain develops also by the reflex mechanism, as a response to irritation of the cystic duct receptors by stones. A gall-bladder colic can be provoked by physical or nervous strain, jolting motion, ingestion of much fat, etc.

A gall-stone colic develops suddenly. The pain is first diffuse and is felt in the entire right hypochondrium. Later it localizes in the region of the gall bladder or in the epigastrium. Pain is piercing and so severe that cannot be tolerated without pain-relieving preparations. The patient groans and tosses in bed vainly seeking for a convenient posture. The pain can specifically radiate upwards, to the right posteriorly, to the right shoulder, neck, the jaw, and into the right subscapular region. Pain can radiate also into the heart to provoke an attack of angina pectoris.

Pain can continue from several minutes to a few hours and even days, periodically subsiding and strengthening. Intensified contractions of the gall bladder promote further propulsion of the stone (not more than 1.5 cm in diameter) from the neck or the cystic duct into the common bile duct. Sometimes, after relaxation of the spasm the stone may return back to the " silent" zone (the fundus of the gall bladder). In both cases, the pain attack discontinues as suddenly as it begins. The patient's condition rapidly improves. The attack can often be alleviated by applying warmth or giving

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

spasmolytics (atropine sulphate, 16 ml of a 0.1 per cent solution, or papaverine hydrochloride, 2 ml of a 2 per cent solution subcutaneously). This is a valuable differential-diagnostic sign: these remedies fail to relieve pain in acute cholecystitis, while warmth (e.g. a hot-water bottle) is con-traindicated because warmth intensifies blood inflow and the inflammatory process.

spasmolytics (atropine sulphate, 16 ml of a 0.1 per cent solution, or papaverine hydrochloride, 2 ml of a 2 per cent solution subcutaneously). This is a valuable differential-diagnostic sign: these remedies fail to relieve pain in acute cholecystitis, while warmth (e.g. a hot-water bottle) is con-traindicated because warmth intensifies blood inflow and the inflammatory process.

If the colic is long-standing, jaundice may develop at the end due to a spasm of the common bile duct. The jaundice usually is not intense and is only transient (2 to 3 days).

Gall-stone colic is usually attended by nausea and recurrent vomiting. The reflex mechanism explains the fever which often attends the pain attack. The fever ends with the attack. If fever persists, it indicates its connection with inflammatory complication of cholelithiasis. This is confirmed by an increase in leucocytosis, ESR, and a sharp deterioration of the patient's general condition.

The patient may sometimes be obese, with xanthomatous plaques (cholesterol deposits) on the upper eyelids (less frequently on the other parts of the skin). The abdomen is distended; surface palpation reveals tension of the anterior abdominal wall, especially in the region of the right hypochondrium, and also excessive tenderness of this region. As pain is abated, the muscular tension subsides, and the tender edge of the liver can then be palpated. The gall bladder can sometimes be palpated as an oval or pear-shaped elastic body.

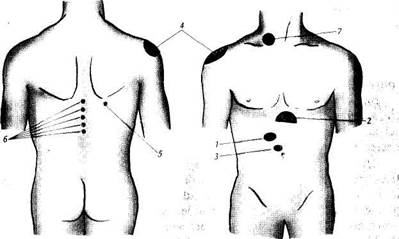

Tender points and sites of hyperaesthesia can sometimes be determined on the body according to Zakharyin and Head (Fig. 100). These are as follows: (1) the region of the gall bladder (its projection on the skin); (2) epigastrium; (3) pancreato-biliary-cystic point; (4) shoulder zone; (5) point of the scapular angle; (6) paravertebral points to the right of the 8th to 1 lth thoracic vertebra; (7) phrenic nerve site (tender to pressure in the region between the anterior heads of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle (phrenic symptom, or de Mussy-Georgievski symptom).

Some laboratory and instrumental studies reveal signs of cholelithiasis in the full absence of its symptoms. Blood test shows an increased cholesterol content. Duodenal probing (carried out in remission) can sometimes reveal fine stones (microliths) and a large quantity of cholesterol crystals. The most important diagnostic technique in cholelithiasis is contrast roentgenography (cholecysto- or cholangiography and echography studies). These techniques help reveal stones in the gall bladder and the bile ducts.

Course and complications. The course of cholelithiasis is quite varied. Non-complicated cholelithiasis can manifest itself by only one attack of gall-stone colic. The attacks however are usually recurrent. They follow

Fig. 100. Points and zones of pain in cholelithiasis.

one another at short intervals or can occur once in 1 or 2 years, and even less frequently. Rare cases are known when the patient recovers spontaneously with the discharge of a small stone into the intestinal lumen. Long-standing cholelithiasis is usually attended by infection. The main disease is then aggravated by symptoms of cholecystitis or cholangitis.

Obstruction of the gall-bladder neck is a complication of the disease. It can cause hydrops. Obstruction is manifested by a most severe pain attack. Following several weeks, an enlarged gall bladder can be palpated. It is elastic and painless. In the absence of gall-bladder adhesion to the neighbouring organs (due to pericholecystitis) the bladder can easily be displaced together with the liver during deep respiration and by palpation.

In hydrops, the gall bladder is filled with a yellowish or colourless fluid (white bile) which is formed due to absorption of bile elements in the gallbladder walls and effusion of serous exudate from the gall-bladder mucosa. If an infection joins, empyema of the gall bladder develops and the patient's condition is sharply deteriorated. The patient feels chills; the body temperature is high; pain in the right hypochondrium develops again. Neutrophilic leucocytosis and increased ESR are characteristic. If the gall-bladder entrance is fully obstructed by a stone, the bladder may become gradually affected by cirrhosis and its walls become sclerosed.

The common bile duct may be obstructed by a stone that passes from the gall bladder. As a rule, the stone is retained at the sphincter of the hepatopancreatic ampulla. Soon after the pain subsides, signs of obstruc-

30*

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

tive jaundice develop. The common bile duct is obstructed completely when a mechanical closure (by a stone) combines with a spasm and inflammatory oedema of mucosa of the bile duct (cholangitis) that hinder bile outflow. The gall bladder does not usually increase despite congestion because its walls are affected by the attending inflammation and are no longer distended (Courvoisier-Terrier syndrome).

tive jaundice develop. The common bile duct is obstructed completely when a mechanical closure (by a stone) combines with a spasm and inflammatory oedema of mucosa of the bile duct (cholangitis) that hinder bile outflow. The gall bladder does not usually increase despite congestion because its walls are affected by the attending inflammation and are no longer distended (Courvoisier-Terrier syndrome).

Bile outflows to the duodenum when stones move from the narrow to the wider part of the common bile duct (valve stones), or during transient relaxation of the gall-bladder walls. Jaundice intensity thus increases and decreases periodically; the colour of faeces changes accordingly.

Another complication of the disease is perforation of the gall bladder (less frequently of the common bile duct) with development of the outer or inner vesico-intestinal passages and sometimes bile peritonitis. Long presence of stones in the gall bladder can cause cancer, and prolonged obstruction of the common bile duct with bile congestion and infection of the bile ducts often provoke biliary (cholestatic) cirrhosis of the liver.

Treatment. Conservative treatment provides better outflow of bile and decreases the tendency to further formation of stones. The patient is recommended to lead a more active life, and prescribed frequent meals with restricted intake of cholesterol-containing foods, mineral water, and cholagogues. Various antispastic and pain removing preparations are prescribed (atropine, papaverin, warmth, etc).

Surgical treatment of cholelithiasis is indicated in the presence of hydrops or empyema of the gall bladder, obturation of the common bile duct with obstructive jaundice, perforation of the gall bladder with development of fistulae or bile peritonitis, or in the presence of frequent attacks of gall-stone colics that fail to be removed by conservative treatment.

Prophylaxis consists in removal of metabolic disorders and causes of bile congestion. The patient is recommended regular meals, exercises, active mode of life, rational diet, and measures to prevent constipation.

! Cholecystitis

Cholecystitis is the inflammation of the gall bladder. The incidence of the disease is rather high; women are mostly affected.

Aetiology and patbogenesis. Various infections, autolytic affections of the gall-bladder mucosa associated with regurgitation of pancreatic juice into the gall bladder, and helminthic invasions are important factors provoking cholecystitis. Virus aetiology of cholecystitis has been recently proved (Botkin's disease virus). Cholecystitis of toxic and allergic nature also occur. The aetiological role of infection in development of cholecystitis is confirmed by bacteriological studies of microbial flora of B bile obtained

during operation or by duodenal probing. Infection may enter the gall bladder by enterogenic (from the intestine), haematogenic (from remote foci of infection such as affected tonsils, carious teeth, etc.) and lym-phogenic routes. The aetiological importance of lamblia in the development of cholecystitis is disputable.

Bile congestion in the gall bladder predisposes to cholecystitis. The disease can be provoked by gall stones, dyskinesia of the bile ducts (under the effect of various psychoemotional factors, endocrine disorders, dysfunction of the vegetative nervous system, numerous nerve reflexes of the pathologically changed organs of the digestive system, etc.), anatomical properties of the gall bladder and bile ducts, ptosis of the internal organs, pregnancy, inactive mode of life, rare meals, habitual constipation, etc. Acute and chronic cholecystites are differentiated.

ACUTE CHOLECYSTITIS

Pathological anatomy. Acute catarrhal cholecystitis is characterized by a mildly enlarged gall bladder containing serous or seropurulent exudate. The mucosa is swollen and plethoric. The inflammation affects the submucous layer as well (it is infiltrated by leucocytes). In purulent forms of cholecystitis, the lumen of the gall bladder is filled with purulent exudate; its walls are richly and diffusely infiltrated by leucocytes. The mucosa is oedematous, hyperaemic; erosion is frequent; deep ulcers or necrotic affection of the entire depth of the bladder wall occur in graver cases, gangrenous cholecystitis (gangrene of the gall bladder).

Clinical picture. Acute cholecystitis begins vigorously: sharp pain arises in the left hypochondrium which involves the entire upper abdomen and radiates into the right side of the chest, the neck, and sometimes into the heart. Pain may resemble biliary colic, but it is less intense. Pain continues for a few days; if not treated, it may continue for longer time. Pain is often attended by nausea and vomiting with a small amount of bile. Pain arises as a result of inflammation of the wall and serous coat of the gall bladder and distension of the overlying peritoneum. The temperature rises to 38 and even 40 °C and the patient feels chilly. Sometimes a mild jaundice develops due to inflammatory oedema of the mucosa of the common bile duct and obstructed bile outflow. The tongue is dry and white-coated. The abdomen is distended, the movements of the anterior wall are limited, or the wall is not involved in the respiratory act at all.

Surface palpation first reveals local and then diffuse tension in the abdominal wall and sharp tenderness in the right hypochondrium. Acute cholecystitis is also characterized by some other symptoms: Zakharyin's symptom (sharp pain in the region of the gall bladder when it is tapped or pressed), Vasilenko's symptom (sharp pain in the region of the gall bladder when it is tapped over at the height of inspiration), Obraztsov-Murphy

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

< J,

symptom (sharp pain in the right hypochondrium when the examiner's hands press the gall bladder at the height of inspiration), Ortner's symptom (pain during tapping over the right costal arch by the edge of the hand). If inflammation extends onto the peritoneum overlying the gall bladder, Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom is positive. In this case, in the presence of gangrenous cholecystitis (gangrene of the gall bladder) and possible perforation of the gall-bladder wall, a dangerous sign appears, i.e. the peritoneum friction sound at the point of its projection onto the abdominal wall. In moderate tension of the abdominal muscles it is sometimes possible (especially in purulent cholecystitis) to palpate an enlarged and very tender gall bladder. The liver does not usually increase, but its tender edge can sometimes be palpated. The de Mussy-Georgievsky symptom (tenderness at the point of the phrenic nerve, between the heads of the ster-nocleidomastoid muscle) can often be positive. Zones of skin hyperaesthesia (Zakharyin-Head symptom) can be found below the inferior angle of the right scapula and in the region of the 9th- 11th interspaces. Leucocytosis is shifted to the left and the ESR increases.

Duodenal probing (that can only be done during abatement of the process) often fails to obtain B bile; or a cloudy whitish exudate poor in bilirubin can only be obtained. Bile samples contain much leucocytes, mucus, and cells of desquamated epithelium. The corresponding flora can be revealed in bile cultures.

Course. Patients with catarrhal cholecystitis recover comparatively soon. But the disease may convert into the chronic form. Acute purulent cholecystitis has a graver course, with signs of toxicosis, peritoneal irritation, high neutrophilic leucocytosis and considerably increased ESR. Signs of general toxicosis are more vivid in gangrene of the gall bladder, while in its perforation the symptoms of peritonitis join the picture.

Treatment. The patient must be admitted to hospital. Extirpation of the gall bladder is indicated in purulent and gangrenous forms of acute cholecystitis. Strict bed rest and abstention from taking food during the first two days following the attack are prescribed to patients with catarrhal cholecystitis. Later food should be given in small portions, 5-6 times a day, according to Pevzner. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (oletetrin, 100 mg, 2-3 times a day intramuscularly, during 5-7 days) and spasmolytics (papaverine hydrochloride, 2 ml of a 2 per cent solution, 3 times a day sub-cutaneously) should be given.

CHRONIC CHOLECYSTITIS

Chronic cholecystitis may develop after acute cholecystitis but in most cases it develops gradually as an independent disease.

Pathological anatomy. The inflammatory process affects all layers of the gall-bladder wall in chronic cholecystitis. The bladder wall gradually scleroses, grows thicker, and calcium is deposited in the tissue. The gall bladder diminishes in size and adheres to the neighbouring organs. The adhesions deform the bladder to interfere with its normal function and to provide conditions for inflammation with periodic exacerbations.

Clinical picture. The patient complains of dull boring pain in the right hypochondrium which usually develops 1-3 hours after taking abundant (especially fat and roasted) food. The pain radiates upward to the region of the right shoulder, neck and the scapula. If cholecystitis concurs with cholelithiasis, sharp pain may arise (like in biliary colic). Dyspeptic signs are also present: bitter and metallic taste in the mouth, eructation, nausea, abdominal flatulence, and alternation of diarrhoea with constipation. The disease is sometimes not attended by pain except that the patient feels heaviness in the epigastrium or right hypochondrium, and dyspepsia develops. The temperature is often subfebrile.

The appearance of the patient and his nutrition are usually normal. Moderate obesity is sometimes observed. Examination of the abdomen can reveal its flatulence (either uniform or predominantly in the upper portion).

Surface palpation of the abdomen reveals sensitivity and sometimes pronounced tenderness in the region of gall-bladder projection. Muscular resistance of the abdominal wall is usually absent. De Mussy-Georgievsky, Ortner's, Obraztsov-Murphy, and Vasilenko's symptoms are positive. The liver is usually of normal size but in the presence of complications, such as hepatitis or cholangitis, the liver may be slightly enlarged with firm and tender (to palpation) edge. The gall bladder is impalpable.

The blood changes (during exacerbation) are characterized by moderate leucocytosis and mildly increased ESR.

Signs of inflammation (mucus, leucocytes, desquamated epithelium) can be found in B bile. If inflammation involves bile ducts (cholangitis), C bile contains the same signs of inflammation. The vesical reflex (B bile) is sometimes impossible to obtain even by repeated probing. This indicates disordered contractility of the gall bladder which is typical of chronic cholecystitis. Bacteriological studies of B bile reveal the character of microbial flora. Polarographic study of bile can reveal signs of inflammation.

Cholecystography shows changes in the configuration of the gall bladder and the absence of its distinct contours. This indicates upset concentrating capacity of the gall-bladder mucosa. After taking a stimulating meal the gall bladder contracts insufficiently.

Course. The course of the disease is characterized by alternation of exacerbations and remissions. The disease can be exacerbated by abuse of

Special Part

Chapter 7. Digestive System

fatty or fried foods, smoked meat and fish, condiments, alcoholic drinks etc., by acute intestinal infections, and other factors. The process continues for many years and even decades. Cholecystitis is often complicated by inflammation of the bile ducts (cholangitis) or of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

fatty or fried foods, smoked meat and fish, condiments, alcoholic drinks etc., by acute intestinal infections, and other factors. The process continues for many years and even decades. Cholecystitis is often complicated by inflammation of the bile ducts (cholangitis) or of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

Treatment. Patients with exacerbated chronic cholecystitis must be treated in in-patient conditions (like in acute cholecystitis). In interparox-ysmal period, treatment should be given 1-2 times a year in anti-relapse courses: periodic duodenal probing or giving cholagogues in 3—4 week courses (e.g. allochol per os, 1-2 tablets 3 times a day after meals, cholagogic species in the form of infusions, 10-20: 200 ml, half-glass 3 times a day, 30 minutes before meals). Sanatorium and health-resort therapy is also indicated.

Prophylaxis. The disease and recurrent exacerbations should be prevented by taking measures to control bile congestion (exercises, walks and trips, regular and frequent meals with certain restriction) and treat focal infections.

PANCREAS